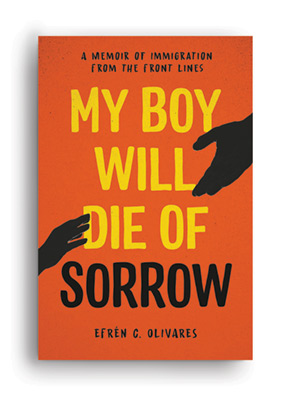

For Efrén Olivares, whose childhood was split between Texas and Mexico, the push to reform US immigration policies and practices is both a marathon and a sprint. He shares his story of legal battles and personal struggles in an emotional new memoir, My Boy Will Die of Sorrow.

By Julia M. Klein

Illustration by Daniel Bejar

An invitation to campus three years ago helped change how Efrén C. Olivares C’05 viewed his own life story.

As Racial and Economic Justice Program Director for the Texas Civil Rights Project, Olivares had represented desperate families fleeing violence and poverty in Central America. With official US entry ports logjammed, they were crossing the border wherever they could. Beginning in spring 2018, the Trump administration, under a “zero tolerance” policy, charged the adults with illegal entry and took away their children, triggering chaos, heartbreak, and media outrage.

Olivares, an immigrant himself, mounted a successful international legal challenge to the policy and worked to unite families. But his address to a group of first-generation and low-income students at Penn in April 2019 marked “the very first time,” he says, “when I started making the connections between my own experience and the experiences of the families of my clients.”

His own family separation had been different, to be sure: less brutal and abrupt, involving parental choice and a happy ending. “What I was seeing my clients being subjected to was so outrageous and so shocking that I didn’t even conceive of myself having gone through something like that,” he says. But Olivares, who directs the Immigrant Justice Project at the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), had endured loneliness and pain of his own when his father left northern Mexico to work in Texas.

For four years, he and his younger brother, Héctor, saw their father at most a couple of weekends a month. Finally, when he was 13, the family decided to relocate to Texas’s Rio Grande Valley. Though Olivares started junior high school speaking virtually no English, he became his high school class valedictorian, and found his way to Penn, Yale Law School—and the zealous practice of human rights law.

Two parallel but contrasting tales—of America as a land of dreams both fulfilled and deferred—are braided together in Olivares’s first book, My Boy Will Die of Sorrow: A Memoir of Immigration from the Front Lines. The title is inspired by a Guatemalan father’s response when Olivares asked what would happen if he was deported without his 11-year-old son.

Published by Hachette Books in July, Olivares’s memoir recounts his personal immigration story and describes his efforts to help other aspiring immigrants surmount legal and bureaucratic obstacles and recover their families. The book has a strong political edge, with Olivares indicting US immigration policy as historically sullied by racism. “Overt racism and white supremacist views have been part and parcel of immigration law and policy in the United States for more than two centuries,” he writes, citing the Nationality Act of 1790, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and the Immigration Act of 1924.

Olivares, who turned 40 in June, says that he “never thought of my life or my journey as remarkable, really.” He was, he thought, “just this kid [who] came to the US and went to school and tried my best,” someone who “struggled to accept that maybe there are some remarkable things about my experience.”

But the memoir, like Olivares himself, has a broader mission. “I hope to remind people that, save for Native Americans, we’re all coming from somebody who came here looking for safety or opportunity,” he says. “So why then are we so cruel to those coming today? What’s the difference?

“We’re told this story that what makes an American an American is not race, it’s not religion, it’s not ethnicity—it’s the ideals in the Constitution: justice, equality under the law, freedom, the pursuit of happiness. But how come we are breaching those otherwise inviolable principles at the border? Why does that border become so meaningful when it comes to these ideas? I posit that the color of the skin of those knocking at our doors might have something to do with that.”

In the memoir, Olivares makes an ironic confession: a lawyer who helped his father gain custody of children from a previous relationship, “separating them from their mother in the process,” first sparked Olivares’s interest in the profession.

“I had no real understanding of what a lawyer does,” he says. “I just thought, ‘That seems cool.’” Much later, at Penn, where he majored in Philosophy, Politics and Economics, he experienced a “social justice awakening” that shaped the kind of law he would practice.

Olivares spent his childhood in the small Mexican town of Allende, where his family owned “a decent, three-bedroom cinderblock home” whose yard was filled with roses and geraniums, and lived among relatives and friends. But the family situation was complex, and separation was a theme.

Olivares’s father had an earlier, long-term relationship in southern Mexico that produced a boy and two girls. A self-employed truck driver, he was often absent, and his partner had problems of her own. When their relationship dissolved, he took the children north with him—a move assisted by their maternal grandmother and later ratified by a Mexican court. Though it was the right decision, Olivares says, “it was extremely hard for them and traumatizing to the point that, when they were teenagers, they left my father to go back to their mother.”

Months later, they returned to northern Mexico, in part for better educational and economic opportunities, Olivares says. But the revived connection with their mother held; they stayed in touch and visit her regularly to this day. “To me,” Olivares says, “the takeaway is that no matter what your mother does, you love her, and you want to be with her, and being ripped apart is still traumatizing to a child.”

When Efrén was nine, his father—whose own father had been born in the United States, making them both US citizens—left Mexico in search of employment, and became a school bus driver and janitor in South Texas. “It was only in writing the book and reflecting more about it that I really came to see how difficult that was,” Olivares says, “and the effect that had on who I’ve become as a person,” including his advocacy for immigrant rights.

His parents’ eventual decision to move the whole family across the border was a welcome one—at first. “We were excited about all four of us being together under the same roof,” Olivares says. “The prospect of being together with our father far outweighed the cost of not being around our cousins.”

But the reality of their new life was unsettling. The family, including two of Efrén’s half-siblings, had to cram into a tiny apartment far less comfortable than their Mexican home. He and Héctor shared a single scratchy mattress. “This is worse! Why did we do it?” he remembers thinking.

“Add, on top of that, not speaking the language, not knowing anybody, not having any friends, having fewer family members around,” he says. “So the excitement of rejoining our father was quickly met with the realization that economically we were worse off.”

Héctor Olivares, now residential director of a treatment center in Texas’s Hidalgo County, recalls a similar disappointment. “We were always excited about the whole concept of moving to the US,” he says. “But then, it hits you, the separation from everything you ever had: school, friends, cousins.”

Noting Efrén’s lack of English proficiency, the school insisted that he repeat seventh grade. It seemed like another blow, “but, in retrospect, that was such a good thing,” he says, because it gave him time to master the language before the required eighth-grade standardized tests.

He and his brother attended schools in the district where their father worked—an area so impoverished that nearly every student qualified for a federally subsidized free lunch. In eighth grade, an English teacher offered Olivares after-school aid with pronunciation, but other students were always there “who needed more help than I did with grammar or vocabulary.” So Olivares never got the promised assist. “Now I love having an accent,” he says. “It’s part of my identity, of my heritage.”

Olivares’s high grades gave him a wide choice of colleges. He didn’t know much about Penn, but the University’s financial aid package was the most generous.Arriving in Philadelphia was a shock: “It’s cold, and the radio stations don’t have music in Spanish, like they all do in South Texas. The food is different—it’s not all Mexican or Tex-Mex.” He remembers thinking: “Oh, this is the US.”

“It was hard. I was feeling very homesick,” he says. “I wrote a letter to my parents saying how much I missed them, and how much I wanted to be back.”

One cultural disconnect, described in the memoir, involved an academic advisor who denied him permission to take a fifth course one semester. Olivares wanted to add a Spanish literature class, on Cervantes’s novel Don Quixote—not an outsized challenge for a native speaker. But the advisor expressed concern that Olivares’s parents would place an angry call to him if their son’s grades suffered. “His response was unfathomable to me,” Olivares says. His parents didn’t even speak English. “They had zero connection to my life at Penn.”

But Olivares did find community at the University, befriending international students from Mexico, members of the broader Latinx diaspora, and classmates who shared his academic interests. At the Albert M. Greenfield Intercultural Center, he acquired both a work-study job and “a home away from home.” It was the center that invited him back to campus in 2019, and it plans to host him again in late September in connection with his memoir.

Olivares’s “social justice awakening” began with a course titled Writing About the Essay. Reading Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own helped make him “a proud feminist,” he says. He also loved his classes on political philosophy and the history of economic thought. “Seeing what I perceived to be injustice in the world reaffirmed my desire to go to law school,” he says, “but now with this twist to do social justice and public-interest law.”

Graduating summa cum laude, he applied to 15 law schools. He was accepted to 13. Only Stanford said no; Penn waitlisted him. (“I won’t deny that it stung a little bit,” he says.)

Olivares chose Yale and thrived there, becoming astudent director of the Schell Center for International Human Rights and articles editor of the Yale Human Rights and Development Law Journal.

His father, who had a heart condition, died the fall semester of Efrén’s second year of law school. It was a major emotional blow that temporarily diverted Olivares’s career trajectory. “He took over the family financially,” his brother Héctor recalls. “That was very impressive. He didn’t have to do that.”

After graduation, Olivares worked at the Houston law firm of Fulbright & Jaworski LLP, “doing corporate litigation, representing the big multinational companies, making way too much money for a 26-year-old,” he says. He used much of it to help his mother pay off her house.

After four years, he felt able to pursue his real interests. As a Bernstein International Human Rights Fellow at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, he traveled to Guatemala with a delegation to chronicle human rights abuses.He also gained a useful connection: the fellowship was named for Robert L. Bernstein, the longtime president of Random House and a strong human rights advocate, who died in 2019. Bernstein’s son Peter and his wife, Amy, would become Olivares’s literary agents.

Olivares landed at the Texas Civil Rights Project, in Alamo, Texas, in 2013. Based near the border, he initially handled a range of cases, involving the First Amendment, wage theft, disability rights, and other issues. Then, in May and June 2014, came “the first ‘crisis’ of unaccompanied children from Central America coming across the border,” Olivares says. “I was at the right place at the right time to do that work. And that’s when I started focusing my career on immigrant rights.”

In 2015, Olivares, on behalf of the Texas Civil Rights Project, filed a successful lawsuit against the state of Texas, which had been denying US birth certificates to the children of undocumented immigrants. Immediately after the 2016 election, marked by candidate Donald Trump W’68’s castigation of Mexican immigrants and focus on building a border wall, he and his colleagues contacted landowners in the area. Olivares told them, “You don’t have to sell your property. You have the right to force the government to take you to court, and we’ll represent you.”

That was another success. “The eminent domain process is so inherently slow that,” with a single exception, “every single landowner that we advised and who refused to sign their land over eventually got it back from the Biden administration,” Olivares says. “I am extremely proud of that fact.”

Mimi Marziani, who became president of the Texas Civil Rights Project in February 2016, quickly promoted Olivares to her leadership team. Praising his “brilliant legal mind” and “deep compassion,” she says: “One of the hardest things in law is to push away the minutiae and quickly grasp what is fundamentally important about a situation—and he has that skill.”

Marziani was fundraising in New York in May 2018 when Olivares called to report a problem. “I’ll never forget the conversation,” she says. Olivares conveyed the experience of a federal public defender he knew: “All of a sudden, she showed up in court, and rather than the normal docket of illegal entry, maybe some drug cases, suddenly there’s dozens of parents crying, asking where their kids are. And nobody knew—not the judge, not the prosecutors, not the immigration agents.

“When he heard that fact pattern, he quickly grasped that this was likely to be a manifestation of [Attorney General] Jeff Sessions’ ‘zero tolerance’ policy,” Marziani says. “I believe that he was one of the very first people in the country to realize that this was being rolled out in a systematic way. He helped me understand very quickly what a crisis it was.” As a result, she says, “we decided to push every ounce of resources we could toward South Texas,” tracking separations, filing a complaint with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and reaching out to the media.

Nationally, other organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union and RAICES (the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services), were also active in the fight. But in McAllen, Texas, a major destination for asylum seekers because of its proximity to the Mexican border, the Texas Civil Rights Project and Olivares took the lead.

Thousands of families were fleeing Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador because of “gang violence, extreme poverty, and, in Guatemala in particular, extreme anti-Indigenous discrimination,” Olivares says. The Trump administration’s initial response was to turn asylum seekers away from official ports of entry once a daily cap was reached (a practice known as “metering”). Prevented from entering legally, families crossed the Rio Grande River, in many cases deliberately seeking out US Border Patrol agents to start the asylum process. “They were going the only way the system would allow them,” Olivares says.

To win asylum, he says, those seeking protection need to show they face threats to their life or safety in their home countries, and that their own governments or police forces can’t protect them. They also must demonstrate that they are being targeted for their “race, nationality, religion, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.” Olivares has argued that gender and LGBTQ status should be included in that last category, but not all courts have agreed.

Historically, Olivares explains, Border Patrol agents have had discretion about whether to refer asylum seekers entering the country illegally for criminal prosecution, and such referrals were uncommon. The “zero tolerance” policy eliminated that discretion. Going to court entailed parents’ separation from their children “if only for a few hours,” Olivares says. The catch was that, at that point, these “unaccompanied alien children,” as they were designated, fell under the jurisdiction of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which was sending them to detention centers and other facilities around the country. In many cases, neither the US Department of Homeland Security, which oversees the border, nor HHS kept adequate records of the process.

My Boy Will Die of Sorrow captures the frenzy of those days. With court permission, Olivares and his small Spanish-speaking team showed up early each morning to federal court to talk to shackled and traumatized parents whose children had been wrested away, and who had no idea when they would see them again. “I interviewed dozens of these parents,” he writes, “and heard firsthand how Border Patrol agents took their children from them through deceit, subterfuge, and sometimes outright violence.”

He met a woman whose husband had been beaten to death in a field, who had left Guatemala to save herself and her 11-year-old son. Border Patrol agents had separated them. Another mother had fled Honduran gangs with her six-year-old son; he had medical problems, and he, too, was missing.

Maggy Krell, then chief legal counsel for Planned Parenthood Affiliates of California and now special advisor to the California attorney general, traveled to South Texas to provide pro bono assistance. “It was pretty chaotic,” she recalls, “and very terrifying for the families. For a lawyer, it was a dizzying array of changing rules and policies and bureaucracies, and how to figure out how best to intervene was part of the challenge.” Later, she would help reunite that Honduran mother and son, and would go on to win their asylum case.

As a former attorney for US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Laura Peña had litigated the government’s side of the issue. But when she heard a Father’s Day rally speech by Olivares, livestreamed on Facebook, she was so moved that she left a private immigration law practice in California to become a visiting attorney at the Texas Civil Rights Project. She is now legal director of its Beyond Borders program.

“The world was looking for leadership,” she says, and Olivares “really stepped up.” At the height of the tumult, “he was so busy and dogged and committed,” she adds. “And even though this was really a marathon that lasted months, maybe years, he was always sprinting.”

The Trump administration said at the time that zero tolerance was meant to deter the growing number of asylum seekers. In Olivares’s view, family separation was integral to that project, not merely its unfortunate byproduct.

“There was no plan for reuniting anyone,” he says. “They didn’t care about reuniting them. That was never their concern. Their concern was just to inflict as much pain and suffering as possible. There was no care for the family relationship.”

The Texas Civil Rights Project logged 382 cases of family separation, ultimately finding lawyers to represent 120 families. Some of the asylum claims were granted; some were denied; others are still pending, Olivares says. Still other families made it to their US destinations and found representation there. Others were deported. The project lost track of about 100.

Most families eventually were reunited, thanks to advocates such as Olivares. But not all. “I am now thinking that in 20, 30 years, we’re going to hear stories of children who are still looking for their parents or finding them, like out of the Argentinian dictatorship,” he says. “It’s really hard to come to terms with it.”

The peak of the crisis lasted less than a month, from mid-May to June 20, 2018, when President Trump’s executive order officially ended the family separation policy. Separations continued after that, Olivares says, but more sporadically. One key factor in the turnabout, Olivares says, was the leak, on June 18, of an eight-minute audio recording from a South Texas detention center where children were crying and begging for their parents. “In the audio, you only hear their cries and their voices. You don’t see the color of their skin,” he says. “That’s why it was so powerful, in my view.”

Both Olivares’s leadership and views on immigration impressed Margaret Huang, president and chief executive officer of the Southern Poverty Law Center. In November 2020, she tapped him to serve as deputy legal director in charge of the organization’s Immigrant Justice Project.

“We hired Efrén because of his extensive experience not only doing litigation on immigrant justice issues, but also his strategic thinking about the threats to immigrant communities in the country,” she says. “What I appreciated about Efrén’s work is that it was encapsulated in a framework of understanding how white supremacy drives so much of the anti-immigrant sentiment and policymaking.”

For Olivares, it was a chance to do the work he loved on a wider, more ambitious scale. At SPLC, he now supervises a staff of about 50 attorneys and others advocating on behalf of detained immigrants, other immigrant workers and families, and asylum seekers.

The first step in composing a book about his experiences was showing notes from his 2019 Penn presentation to a cousin, José Antonio Rodríguez, an associate professor of creative writing at the University of Texas-Rio Grande Valley. Rodríguez was encouraging.

Writing a memoir while working full-time—and parenting two young children, with his wife, Karla, an occupational therapist—wasn’t easy. In college and law school, Olivares had been a night owl. But he found he wrote best in the dawn hours, between 5 and 7 a.m., before his children woke up. “The other thing that was difficult,” he says, “was being vulnerable about my experience and opening up in that personal way that I have never had to do.”

Olivares remains passionate about immigration and America’s tortured response to it. “Even the starting point of [casting] immigration as a problem is already a narrative position,” he says. “This notion that there’s a surge, that ‘they’re coming in droves,’ is created and reinforced by anti-immigrant advocates, people who don’t want immigration—those who are themselves descendants of immigrants, by the way.

“There is a need for an orderly way for people to come to the US, especially those who are fleeing death and persecution, and we don’t have that—it’s very limited. The system is plagued with abuses. There’s a shortage of workers right now, and yet we’re turning people away from the border. The other piece of it is this idea that we cannot process the immigrants on the border, that ‘it’s so many of them and we’re overwhelmed.’

“We’re the most powerful country in the world. We have sent rockets to Mars,” he says. “The idea that we cannot cobble together some staplers and copy paper to process people at the border is just unacceptable, to say the least. That argument is disingenuous, frankly. It’s a lack of political will to really live up to the dream that is the United States.”

Julia M. Klein is a Philadelphia freelance journalist and a frequent contributor to the Gazette. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaMKlein.