Penn’s Stavros Niarchos Foundation Paideia Program aims to foster dialogue, civic engagement, community service, and wellness—and both students and faculty are enthusiastically signing on. But the program’s contours can be murky, and its role in bridging campus divisions remains a work in progress.

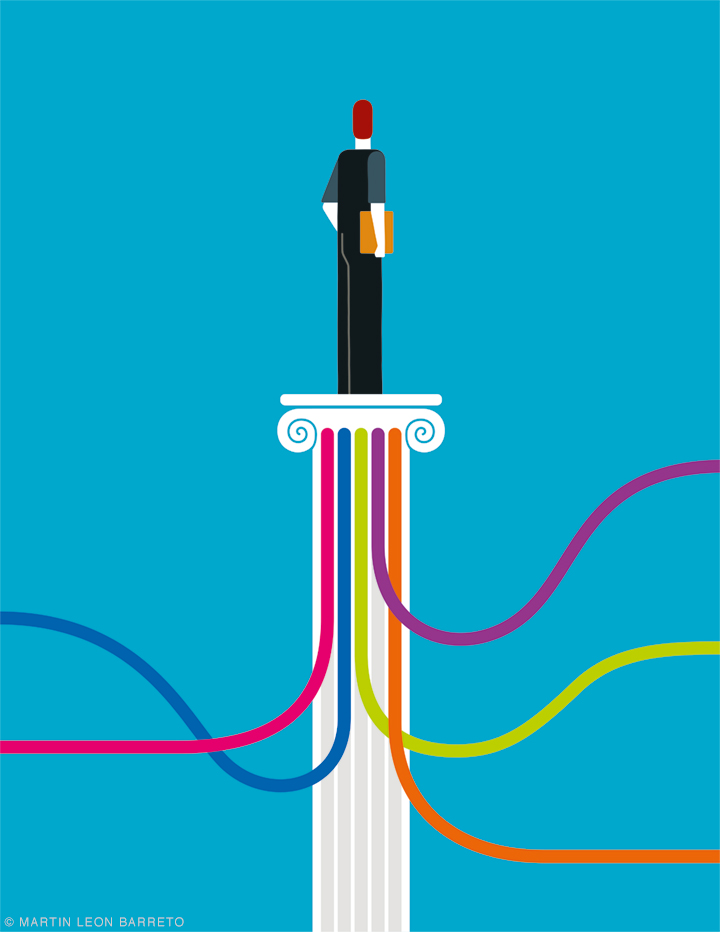

By Julia M. Klein | Illustration by Martin Leon Barreto

It’s a Monday morning in late February, the week before spring break. “We’re going to start with a wellness exercise,” Lia Howard C’01 Gr’11 tells her class. “Does anyone know what this is?” She breaks off a sprig of eucalyptus and passes it around the seminar room. “Once you have your leaf,” she continues, “I want you to just crush it in your hand. It may be a little syrupy. Then just smell.” The crushed leaves produce a distinctive fragrance: minty, medicinal, and soothing.

“We’ve been doing a lot with breathing,” Howard says. “We’ve talked a lot about relaxing before going into conversation. This is another way to tell your body that it’s OK to relax.”

Not every class in Penn’s Stavros Niarchos Foundation Paideia Program incorporates aromatherapy. But the emphasis on student well-being isn’t unique. Howard, a political scientist with a buoyant, gently encouraging manner, happens to be the program’s student advising and wellness director, and her seminar, “Political Empathy and Deliberative Democracy in the US,” has an unabashed emotional dimension. In both topic and format, it embodies Paideia’s focus on “dialogue across difference,” while touching on the program’s other three pillars: citizenship, service, and wellness.

This morning Howard’s Penn class is discussing the United States’ distinct political cultures, the values they embrace, and how those values shape expectations of government. “Equality and liberty do an interesting dance with justice,” Howard says. Students pair up with conversation partners: first to craft a definition of political empathy, then to contemplate different strands of their own identities, including ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation.

Julia Fischer C’24, a political science and Hispanic studies major, says this is her first Paideia class, and she appreciates its emphases: “A lot of political science classes are focused on lectures and reading articles and research. But we do a lot more with conversation and applying what we’re learning—especially when it comes to conversing with others about our political beliefs.” The course, she says, also delves into “the fundamental issues that have been nagging at me during my time at Penn, like polarization” and “how we interact with other people in the political system.”

Howard’s political empathy course—which includes a healthy roster of reading, writing, and research assignments, along with wellness tips—developed out of an earlier one she cotaught on civic dialogue and engagement. It draws students eager to become a community, she says, and many stay in touch with her, and with one another. “They want relationship. They want to connect with people,” she says.

In case you were wondering, “Paideia” is supposed to rhyme, more or less, with “Maria.” To forestall confusion, the program has a video on its website about the pronunciation. Nevertheless, some faculty and students continue to go their own way (Pie-DAY-a is one popular alternative). Translation of the Greek word presents another challenge. Broadly speaking, it refers to a holistic, or well-rounded, education that serves as preparation for citizenship. “It has to do with educating the whole person,” explains Andreas C. Dracopoulos W’86, copresident of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, in the same video. “It starts with the soul [and] becomes a way of life. It’s about civic engagement and civil discourse. It’s about learning to do what’s good for the community.”

The foundation, with offices in Athens, New York, and Monaco, gave Penn $6 million in 2019 to launch a five-year pilot program. It funds two other similar university enterprises: the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University and the SNF Ithaca Initiative at the University of Delaware. “We all have a shared emphasis on supporting pluralist democracy, dialogue, citizenship,” says Leah Seppanen Anderson, the SNF Paideia Program’s executive director. The foundation has since given Penn two more grants: $1.6 million in 2021, and $13 million last year to extend the program through 2029.

Sigal R. Ben-Porath, the Penn program’s faculty director since September and the MRMJJ Presidential Professor of Education, says Paideia aims to foster “a campus atmosphere focused on dialogue and engagement, and the kind of wellness that comes with that, both for individuals and for communities.” That entails cultivating “the attitudes and the skills that are necessary for learning and engaging as equals.”

With the University’s ideological and political divisions exacerbated by the war in Gaza, those attitudes and skills may be more relevant than ever. “The fall has been very challenging,” says Ben-Porath, whose books include Cancel Wars (2023) and Free Speech on Campus (2017). “It also demonstrated for us the true value of the opportunities that we provide. We have students who are very engaged and active on different sides of this current conflict. What we found is that they were very deeply committed to expressing their perspective, but also that they were immensely committed to hearing each other out.”

“I see the Paideia Program as being the civic component of a liberal arts education.”

Paideia embraces both curricular and extracurricular initiatives. The first four Paideia courses were offered during the 2020 spring semester, on the eve of the pandemic shutdown. Penn now has about 70 “Paideia-designated” undergraduate courses—some purpose-built, others redesigned or enhanced. Paideia also funds 75 three-year fellowships, with core seminars, a capstone project, and other requirements, for students interested in its ideals. This year 60 freshmen, the highest total to date, applied for the 25 sophomore-year slots, attesting to the program’s popularity.

Paideia money boosts adjunct salaries, and also finances guest lecturers, student internships, travel, special events, and more. On Friday afternoons, Café Paideia gatherings, a recent response to campus turmoil, offer SNF Paideia Fellows, prospective fellows, and their guests a chance to decompress. This summer Howard’s new Political Empathy Lab will send a half-dozen students across Pennsylvania, to state fairs, diners, college campuses and elsewhere, to conduct issue-oriented conversations, keep journals, and “create a toolkit” for such interactions. Some classes travel to Washington, or to more far-flung destinations, such as Greece and Puerto Rico. Paideia Fellow Francesco Salamone W’26 says he and other fellows are hoping to obtain funding for a summer research trip to Iceland.

The Red & Blue Exchange, supported by the Gamba family, brings diverse speakers to campus, with an emphasis on conservative voices. Brian Rosenwald C’06, a scholar in residence who teaches “American Conservatism from Taft to Trump,” runs the exchange. In March, he moderated a panel with two former top communications staffers from the Trump White House, Alyssa Farrah Griffin and Sarah Matthews, both strong-defense, small-government conservatives who have turned against Trump.

“What I’m looking for is someone who might defy a stereotype, someone who has expertise in a given area, someone who has an interesting backstory,” Rosenwald says. “There is a needle to thread. We’re a university. We’re based in facts. We’re based in evidence. You obviously don’t want to bring an election denier to campus.” On the other hand, he says, “I think hearing from people who are [conservative] true believers is really important.”

Penn’s Paideia Program originated in discussions between SNF’s Dracopoulos and then-Penn President Amy Gutmann Hon’22, a political scientist and philosopher who is now US Ambassador to Germany [“Gazetteer,” Sep|Oct 2021].

Michael X. Delli Carpini C’75 G’75, who became the program’s inaugural faculty director, gives this account: “One of the things they were lamenting was the poor state of public discourse—the coarsening of public dialogue, the fact that people didn’t seem to be able to disagree without personal attacks on each other, the difficult problems that the world was facing, and the understanding that universities should play a role in trying to develop citizens better able to discuss tough issues in a civil kind of way.”

Dracopoulos says he and his colleagues had become “concerned by this paralyzing sense of polarization all around us.” In 2017, the foundation announced a $150 million grant to launch the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins to foster pluralistic dialogue and buttress global democracy. “Through the gift, we were able to hire a set of faculty and also fellows that are doing scholarship and work in this area,” says Hahrie Hahn, the Agora Institute’s inaugural director. The institute is also constructing a glass-cube home designed by the Renzo Piano Building Workshop.

According to Dracopoulos, Gutmann was on the phone to him the day after the Hopkins announcement.

“Why not at Penn, your alma mater?” she said.

“Great idea,” he recalls responding. He says he added, jokingly: “You never asked.”

Within days, he says, Gutmann had presented “a full-fledged proposal.”

Delli Carpini, former dean of the Annenberg School for Communication (and now the Oscar H. Gandy Emeritus Professor of Communication and Democracy), helped design the proposal, and negotiated program details directly with the foundation. “We hit it off from very early on,” says Dracopoulos. Given his research interests, which include political communication and the role of the citizen in democratic politics, becoming the program’s faculty director “felt like a good capstone to my career,” Delli Carpini says.

From the start, the foundation urged Penn not to be overly cautious, to “hit the road running,” Delli Carpini recalls. “At the very beginning, nobody knew what Paideia was. My biggest concern was [being able] to find enough faculty interested in doing these kinds of courses. What has happened is that the reputation of the program has caught on. One of the biggest pleasant surprises for me has been the number of faculty across departments who get the idea of the program, and really want to teach courses that they wouldn’t be able to teach otherwise.”

Dracopoulos notes approvingly “the sheer scale of SNF Paideia,” and the fact that it “is being woven into the fabric of the University and the undergraduate experience.” Ben-Porath says that one of her goals as director is to expand its reach even further to include graduate-level courses and development opportunities for faculty.

What makes for a good Paideia course?

Many with that designation, Delli Carpini explains, are “simply ways of understanding other people, other cultures, other identities” better. In theory, that could include most courses at the University—and indeed Paideia can seem both expansive and amorphous. Delli Carpini says that Paideia-funded courses “try to build in explicitly the concept of dialogue,” as well as the “public interest component” of a subject.

“We’ll work with faculty who already have courses on the books that they want to make more Paideia-like,” Delli Carpini says, “but mostly what we do is help faculty develop new courses” that aim to help students become “good dialogic citizens.” He adds: “There’s no one model of a course that works. Any time we offer a course for a year or two, we’re always rethinking it. It’s a living entity, and it’s evolving. I see the Paideia Program as being the civic component of a liberal arts education.”

Paideia-designated courses are often interdisciplinary. They are eclectic. And they tend to be small (most are capped at 22 students). Paideia’s website says faculty from all 12 Penn schools are involved. Political science, communications, and history are well-represented. Courses also are crosslisted in English, philosophy, anthropology, urban studies, psychology, criminology, education, marketing, biology, engineering, and nursing, among other subject areas.

Sometimes dialogue itself is the subject, as in “Good Talk: The Purpose, Practice, and Representation of Dialogue Across Difference,” taught by SNF Paideia Dialogue Director Sarah Ropp. Rather than advocate for a particular model of dialogue, says Ropp, the class is “about exploring all of the different things that dialogue could mean, and what we could use it for, and the different modes and formats that it can be practiced in.” As dialogue director, she also cofacilitates the weekly Café Paideia gatherings, and offers dialogue-related resources to faculty members University-wide.

A course developed by Annenberg School for Communication lecturer Carlin Romano, “Failure to Communicate,” takes a different tack. It explores breakdowns in dialogue in diverse arenas, including romance, politics, show business, law, science, and war. Romano’s syllabus, which includes 24 films, says the course’s aim is “to bring literary, philosophical, psychological, cinematic, and historical perspectives” to bear on the subject. Romano notes that he offered his students a variety of topics for recent midterm papers, but the majority focused on a subject close to home: their misadventures with dating apps.

“Academic departments often don’t think beyond their calcified course offerings unless someone jabs them with a new idea,” says Romano, the former longtime critic-at-large at the Chronicle of Higher Education. “Then they sometimes become their best intellectual selves and recognize fresh topics and teaching materials. Paideia wonderfully enables that jabbing at Penn.”

Carolyn Marvin, the Frances Yates Emeritus Professor of Communication, has been teaching “History and Theory of Freedom of Expression,” which examines the philosophical and legal roots of disputation over free speech, since 1980, with periodic updates. “I knew the Paideia Program was interested in civil and political and democratic discourse. And I thought, ‘That’s what my course does.’” So, she says, she approached a Paideia administrator and asked, “How about me?”

Marvin says that the Penn student body is more ideologically diverse than the faculty, and that a couple of her current students lean conservative. “The prevailing public ideology is that if somebody’s feelings are hurt, that’s reason enough to get speech restricted,” she says. “And I’m really interested in making sure that [my students] interrogate that by the time we’re finished.”

The spring seminar “Friendship and Attraction,” taught by Caroline Connolly, associate director of undergraduate studies in the Department of Psychology, is a wellness-related offering. It covers such topics as “sexual attraction in straight cross-sex friendship” and “friends with benefits relationships.” In one class, students, primarily seniors, provided methodological critiques of two qualitative studies—on friendships between queer women and friendships between men of different sexual orientations. “The research question itself can affect what you’re gathering,” Connolly points out. “[Researchers’] own experiences could be coloring this.” But data-based studies also contain biases, she tells the class: “Science is much more value-laden than people are willing to acknowledge.”

Another course, “Biology and Society,” touches on those values. It explores the intersections of biology with issues such as informed consent, intelligence testing, eugenics, and artificial intelligence. In a March class, after a presentation by a guest lecturer, students dove eagerly into questions about the advisability and accessibility of genetic engineering. Beyond the prevention of disease, they wondered, could gene editing also be used to shape traits considered more socially desirable? Should it? One student worried about the impact of the technology on people with disabilities. “That has incredibly large moral and ethical implications,” he said.

Mecky Pohlschröder, professor of biology, coteaches the course with another professor of biology, Paul Schmidt. Paideia money helped with course development, as well as funding a teaching assistant and an array of guest lecturers. Polhschröder says that one student told her, with some concern, “I leave the class with more questions than I had when I came in.” That was part of the point, Pohlschröder reassured her. “I love when I see how the students change their minds,” she says.

Some Penn luminaries have embraced Paideia. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, vice provost for global initiatives and the Diane v.S. Levy and Robert M. Levy University Professor, was an early recruit. He developed a philosophy course, “Benjamin Franklin and His World,” focused on ethical challenges that Franklin confronted [“Gazetteer,” Jan|Feb 2023]. It debuted in early 2021, via Zoom, during the University’s pandemic shutdown, and is now available free on Coursera. Another Emanuel course, “How Washington Really Works,” required weekly trips to the nation’s capital to meet with its power players.

This semester Martin E. P. Seligman Gr’67, director of the Penn Positive Psychology Center and the Zellerbach Family Professor of Psychology, is offering “The Science of Well-Being.” It pairs large weekly lectures with smaller sections in which students complete positive psychology exercises. In the fall, Angela Duckworth Gr’06, the Rosa Lee and Egbert Chang Professor in the Department of Psychology, teaches “Grit Lab: Fostering Passion and Perseverance,” which, like Seligman’s class, stresses real-life applications.

Salamone, a Paideia Fellow from Palermo, Italy, has taken both psychology courses. “I always say that I love Paideia because it teaches me what my Wharton education is not teaching me—the reflection component, the thinking more broadly about the values of education, as opposed to the more technical things, the problem solving,” says Salamone. “I would feel that my education was incomplete without the Paideia component.”

Brinn Gammer C’24, a criminology major with minors in Hispanic studies and Latin American studies, is also a Paideia Fellow, and an enthusiast of the program. She says it has funded multiple internships related to her interests in dialogue and wellness.

One involved participation in Penn Walks to Wellness, which organized weekly walks for students, faculty, and staff “just to get them outside and walking and talking.” Another was at the Department of Psychology’s Eden Lab, where she did research aimed at promoting child wellbeing. While she was studying abroad in Chile during spring semester of her junior year, the Paideia Program funded both a criminology internship and language lessons. Back in Philadelphia, she worked at Penn Carey Law School’s Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice, a position not financed but encouraged by Paideia.

For her capstone project, which doubles as her criminology senior thesis, Gammer is researching language barriers in wrongful conviction cases, particularly in Hispanic populations. Her two favorite courses at Penn, “without a doubt,” have been two of her Paideia electives: “Criminal Justice Reform: A Systems Approach,” taught by John F. Hollway C’92 LPS’18, associate dean and executive director of the Quattrone Center; and “Mindfulness and Human Development,” with Elizabeth Mackenzie G’87 Gr’94, an adjunct associate professor at the Graduate School of Education.

The latter was “as cool a class as you can take as an undergrad. It involved us meditating during class, and going through a mindfulness training,” Gammer says. “The attitude of many students here is just, ‘Go, go, go—what can I do to get to the next phase of my life?’ And this mindfulness class I took was the first time there was a genuine pause in that.”

Through campus wellness organizations, Gammer says she has encouraged Penn students “to not be so focused on what comes next—what’s the outcome, what’s the job, what’s the internship I can get.” The lesson of her mindfulness class was “how to enjoy the present moment, and realize that every day is a gift—especially for super-duper privileged kids like us.” But she is hardly immune from the pressures afflicting her classmates. “It’s a constant battle,” she says. “I feel like maybe once or twice a year I have an epiphany where [I say to myself], ‘I’m doing too much. I need to stop.’”

On March 27, for the first time, Paideia cosponsored a University event that waded into the fallout from the violence in the Middle East. Titled “The Conflict Over the Conflict: The Israel/Palestine Campus Debate While Finding Common Ground,” it featured Kenneth S. Stern, director of the Bard Center for the Study of Hate and the author of a 2020 book on the campus debate over the Middle East.

In the Class of 1978 Orrery Pavilion of the Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center, with security personnel guarding the entrances and an audience of about 50, Stern spoke forcefully in favor of free speech on campus. “We need to create an environment where people have the expectation and welcome being disturbed by ideas,” he said. He labeled attempts to curtail and even punish pro-Palestinian speech as “McCarthyism” and urged students to “develop a habit of critically reexamining your own thinking” and “reject simplistic formulas.”

In an audience Q&A after the talk, Madeline Kohn C’26, a Paideia Fellow and urban studies major, posed a challenging question. “I have seen personally among students that even for those [for whom] this free speech absolutism and intellectual inquiry is really exciting, there’s a double burden of either feeling like you’re betraying a community you come from, or a fear of being regarded as a traitor,” she said. “Do you have any advice for students who might be experiencing that?”

Stern suggested that students “be true” to their convictions while also searching for common ground. “Life is too short to not say what you think, but you don’t necessarily have to say everything you think at the moment,” he added.

Delli Carpini regards Paideia’s past hesitancy in engaging publicly with campus turmoil as a shortcoming. “The thing that I wish we could do more of is being able to react in real time to crises like the Hamas–Israel conflict, like an event that might happen on campus that creates real consternation and divides,” he says. “We need to figure out a way we can be more immediately available as a resource. I don’t know how we do that effectively.”

For a while, he says, “the feeling was [that] emotions were just too raw. Sometimes the right thing to do is to stand back. You’ve got to be strategic. But if Penn is going to be a place where difference can be discussed, even hotly contested issues—which it is, in many ways—we need to improve our ability to provide real spaces and guidance for students, faculty, and staff to dialogue on these issues in ways that can be insightful and helpful. And I think Paideia could play a role in that. It does now. It could play a bigger role.”

Paideia faculty meet monthly over lunch, in a “community of practice,” to discuss pedagogical issues. Ropp says that in the fall the meetings spurred “a couple of really meaningful conversations around emotionality in the classroom,” inspiring her to create primers that she has shared across the University. “When Emotions Run High” suggests that instructors acknowledge stressful issues in a nonjudgmental way. “Consider that your gathering space has the potential to be a refuge,” the document says. “Take special care to ensure a safe passage: Greet people warmly and by name as they come in. Have music playing. Bring snacks. Spritz aromatherapy spray. Soften the lighting.” Another resource, “Making Space for Emotion,” advises that faculty “make respect for diverse emotional reactions a core value” and “cultivate emotional literacy.”

Paideia Fellows learn how to engage in respectful political dialogue in their required proseminars. Ben-Porath sees their interactions as a template: “They are not dogmatic. They are not aggressive. They are never hateful. They always are striving to listen and to understand diverse perspectives. And this for me is a model of what I would like the program to offer to other people on campus.”

Penn, too, can do better, she suggests. “From a Paideia perspective,” Ben-Porath says, “I think as a university we haven’t invested our efforts in, first of all, cultivating this shared foundation of knowledge, ensuring that people share a factual basis upon which they can build their diverse perspectives about some of these issues. But, also, I think we centered more of our attention on speech, which is very important, and not enough of our attention on listening, which at a university has to be a component of our commitment to speech.

“In a democracy, it’s enough if you can say your thing. You vote, that’s your expression. You make a statement, you protest, it’s enough that you can talk. But this is not enough when the goal is the learning and the production of knowledge, like it is for schools and universities.

“At the University, if we don’t cultivate a commitment to listening along with the commitment to speech, we are not doing our work. This is where Paideia really supplements some of the current discussion about open expression and its boundaries,” Ben-Porath says. “There is no point in arguing over the boundaries when we don’t ensure that people are able to listen to each other. It matters very little that you can speak if nobody’s hearing you out.”

Julia M. Klein is a frequent Gazette contributor.