On the 65th anniversary of the Penn Course Guide, a deep dive into what contemporary Penn undergraduates actually study—and how their choices have changed over time.

By Trey Popp | Illustration by Lincoln Agnew

Imagine, if you can bear it, a contemporary undergraduate registering for classes at Dear Old Penn. Depending on your age, or your politics, you may have heard enough about the Ivory Tower lately—to say nothing of kids these days—to recoil from the very thought of it. But there she is, perched before a laptop screen, wearing sweatpants and a T-shirt proclaiming END FOSSIL FUELS. Her Path@Penn course cart is almost full: ENGL 2402: What is Capitalism? Theories of Marx and Marxism. URBS 0093: Latinx Environmental Justice. HIST 0819: Queer Life in US History. NELC 0400: Getting Crusaded. CIMS 3204: History of Children’s TV. And, because not even Wharton’s Finance Department has escaped what Elon Musk C’97 W’97 derides as “the woke mind virus,” maybe she can carve out the time to audit FNCE 2540: ESG and Impact Investing. Well, either that or MUSC 1580: Weird Music.

If that picture leaves you shuddering on the verge that separates bewilderment from apoplexy, pause for a moment to imagine our notional sophomore’s classmate down the hall. He’s untucked his Brooks Brothers button-down and kicked off his Sperry sneakers, because he has finally sorted out his schedule, too: HIST 1200: Foundations of European Thought. ENGL 1022: The Age of Milton. ENGL 1820: British Poetry 1660–1914. ECON 4610: Foundations of Market Economies. FREN 3130: French for Business II. Only he wonders if he might swap one out for HIST 3965: History of the International Monetary System. Or take a flier on RELS 1130: How to Read the Bible.

The longer you’ve been away from college, the more plausible these bogeymen may seem. Bemoaning the state of US higher education has become a take-no-prisoners pastime. And though it’s been nearly 40 years since Jesse Jackson showed up at Stanford to chant “Hey hey, ho ho, Western Civ has got to go!”—channeling discontent from one end of the political spectrum—the 2020s have seen coruscating criticism from the other side. Conservative pundits regularly paint vast swaths of academia as meritocratic graveyards where progressive pieties have extinguished rigor. And Penn has come in for its scathing share.

But would alumni strolling down Locust Walk actually encounter one of the students conjured above? Well, it’s not unthinkable. The University has offered all of those courses within the last year or so. But if there are any Quakers who have taken even two of them within that time frame, let alone the full five-course fever dream, they are outliers indeed. Ten total students took Professor David Kazanjian’s English class on Marxism in 2023. Eleven studied Latinx Environmental Justice. Milton attracted nine gluttons for blank verse while seven signed up to study the next 250 years of British poetry. Wharton’s course on Environmental/Social/Governance investing (part of a new undergraduate concentration option) drew 131—tripling the runner-up Foundations of Market Economies. But even the ESG course’s enrollment was less than one-quarter of ECON 0200: Introduction to Macroeconomics (565). And Intro Macro didn’t even crack the top 10 most popular classes at Penn in 2023.

In short, the reigning caricature of contemporary college life misses reality’s bullseye as spectacularly as an archer aiming backwards. But before we paint a more accurate picture of what today’s Penn undergraduates are actually studying, let’s travel back to an era that’s never been accused of going haywire, and imagine a Quaker considering his course options in 1959.

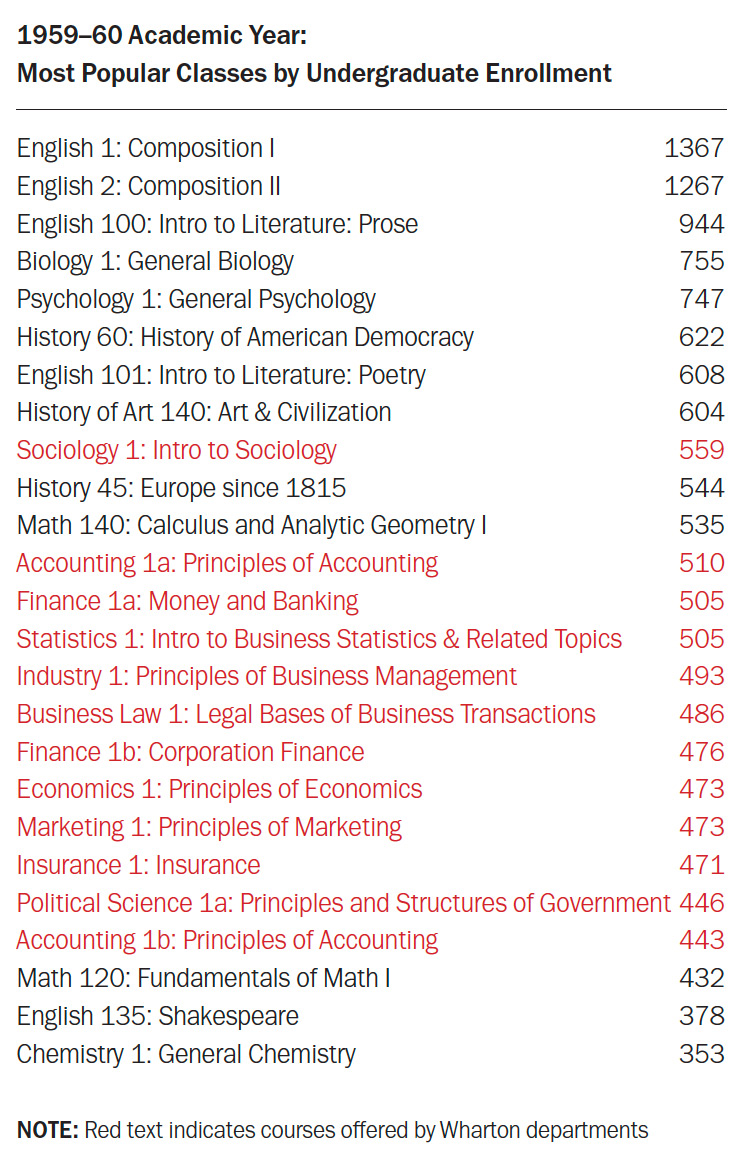

We can guess what he was wearing, too—at least if he heeded the first advertisement printed in the first edition of the Daily Pennsylvanian Guide To Courses. On the inside cover of that inaugural 32-page pamphlet, which cost 25 cents, the Varsity Shop plugged Dacron Blend Suits for $29.90, Dacron Slax for $9.90, and (for the weekend, one supposes) Dacron Bermuda Shorts for $4.90. (The Varsity shared the page with the Original Pagano’s Pizza at 3614 Walnut Street.) And thanks to a pair of exquisitely detailed registrar’s reports that live in the University Archives & Records Center, we know what the most popular classes were at Penn for the 1959–60 academic year:

Eight of the most popular 25 courses in 1959–60 fell within the humanities, and an additional nine belonged to the liberal arts (whose broad definition comprises the natural sciences, formal sciences, social sciences, arts, and humanities). These selections were driven substantially by degree requirements. English 1 & 2, for instance, were mandatory composition-focused classes for students in each of Penn’s undergraduate schools. The College of Arts and Sciences (CAS) required a minimum of five additional humanities courses (plus four of a foreign language), four in specified natural sciences, and two in the social sciences. Wharton also required an introductory course in sociology, a discipline that was then housed within Wharton along with the political science and economics departments. Wharton additionally imposed two literature courses and one course chosen from the College’s anthropology, history, and/or philosophy offerings. Engineering students faced the slightly more flexible demand of six electives within the humanities and social sciences beyond core disciplinary curricula. But Wharton’s liberal arts requirements had an outsized impact on overall course enrollments due to the business school’s size: 1,765 undergraduates, versus 513 in Engineering and 2,446 across CAS, the College for Women, and the School of Fine Arts (which was mostly an undergraduate program in the 1950s). In 1959–60, for instance, Wharton accounted for more than two-thirds of the students in English 135: Shakespeare, and some 96 percent of the students who took Intro to Political Science.

The DP’s Guide to Courses served to alert students to a broader array of academic gems—and stinkers. “For a survey course,” it reckoned that Prof. William Fontaine G’32 Gr’36’s Philosophy 1 was “one of the most penetrating given in the University.” (The Fontaine Fellowships, which were established in honor of Penn’s first tenured African American faculty member, endure to this day.) Zoology 1, by contrast, was “a necessary evil for majors in the science and pre-medical students” on account of Prof. Rudolph Schmieder Gr1922, judged guilty of “entirely failing to stimulate or encourage even interested students.”

The Guide to Courses informed aspiring wordsmiths that English 20: Journalism “employs a ‘learn-by-mistakes’ approach” while English 10: Creative Writing “is the halcyon haven for the fledgling literary dilletante.” History 45: Europe Since 1815 depended on the lecturer: “Case is rated as ‘magnificent,’ while Wolfe is rated as ‘competent, but dull.’” Opinion was “neatly divided” about Edward Sculley Bradley C1919 G1921 Gr1925’s English 184: American Literature Since 1865, with “half believing 184 and Dr. Bradley the two best things since canned beer, half preferring bottled beer.” Chemistry 1 was “generally well-received but for almost total lack of supervision in labs.” Psychology 1, on the other hand was “fortunately undergoing extensive revision” and “any change can only be to the good” for a course “consistently characterized as ‘worthless,’ ‘useless,’ and ‘probably the worst in the university.’”

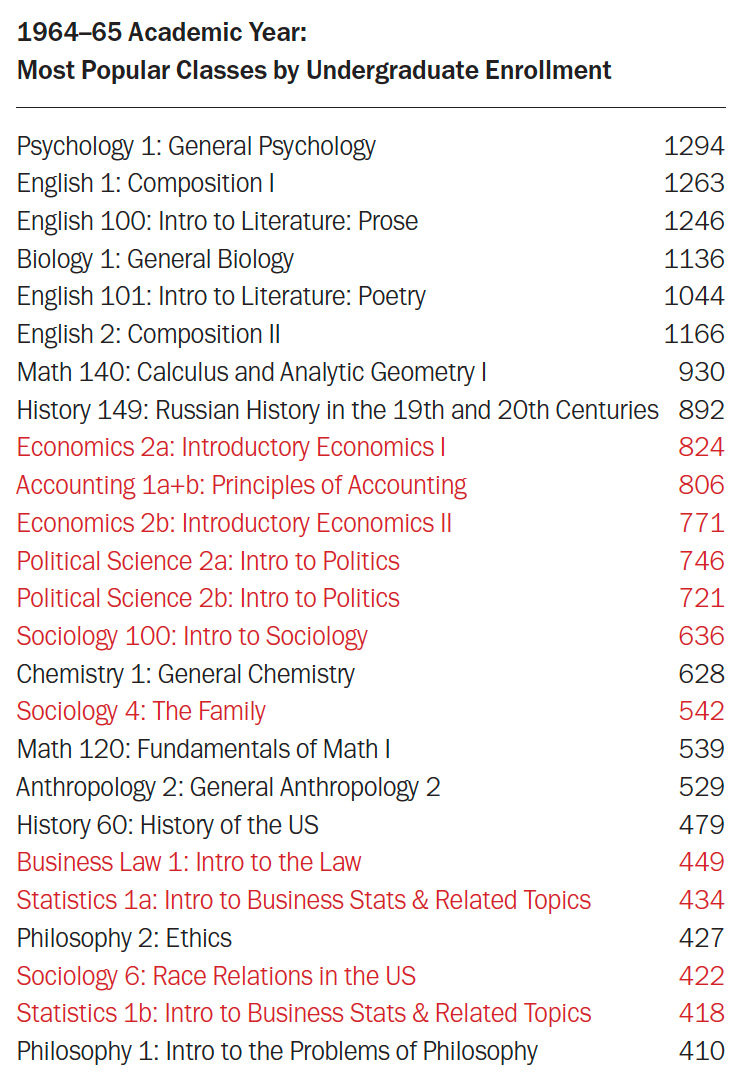

The Fall 1959 Guide was followed by a Spring 1960 edition. It was again 32 pages but its cost increased to 35 cents—even as the Varsity Shop had slashed Dacron Slax by 20 percent and was offering “Polish Cotton Bermudas” for a mere $3.90. Semesterly publication soon gave way to annual editions whose methodology grew more comprehensive. The 1964–65 Course Guide based its judgments on 20,000 questionnaires distributed through campus and the mail.

The good news in 1964–65 was that Psychology 1 appeared to have been resuscitated—depending on who students got. Prof. James Diggory G’43 Gr’48 was “hailed as the new Psych Messiah by most of his enthusiastic students.” Yet the Guide had contrasting “advice to those in [Dr. William Shaw’s] section: ‘Get out!’” Whatever the case, the department had gotten it right enough to make Psych 1 the most popular course of that academic year.

It surely helped that Wharton now required Psych 1 and Sociology 1—in addition to English 1 and 2, English 100 or 101, Anthropology 1 or 2, Philosophy 1 and 2, introductory political science and physics, two courses from a curated list of seven history department offerings, and two in literature. These beefed-up liberal arts requirements stemmed from an ambitious 1960 curriculum overhaul by which Wharton “transformed itself,” as the New York Times judged a decade later, “from a trade school that had a reputation as an Ivy League basement for sons of business fathers to a rigorous college of both applied social science and business fundamentals.” Penn’s School of Engineering and Applied Science (SEAS) also continued to require English 1 & 2 (along with six courses in the humanities/social sciences); CAS students were now able to test out of those introductory English composition classes but had to take at least four courses within the humanities.

Requirements aside, the Course Guide likely had a hand in vaulting two particular history classes into that year’s Top 25. Reviewing History 60: History of the United States, it described Wallace Davies as “a humorous and iconoclastic professor who is determined to burst some [students’] idealistic bubbles,” especially regarding “Uncle Sam’s checkered career from the Reconstruction period until the recent past.” Yet American history was no match for arguably the most praised professor in the annals of University life. About History 149: Russian History in the 19th and 20th Centuries, the Course Guide reported that “rumor has it there is a movement to rename this course to ‘Riasanovsky 149.’ His lectures are nothing less than captivating … spiced with jokes about his father, the Czars, the administration, and especially the Soviets.”

Alexander Riasanovsky—or “The Great One, as at least one quarter of his students refer to him”—was a bona fide phenomenon. The 1963–64 Course Guide reckoned that “Riasanovsky had about as many students in his Russian history class as his grandfather owned serfs.” By 1968–69, it reported that the “historian-entertainer” was such a juggernaut that “early pre-registration has become almost mandatory owing to the high student demand.” (His popularity with students continued into the next decade and beyond, with author Erik Larson C’76 telling the Gazette that Riasanovsky once came to a campus party to “teach us how to drink vodka the Russian way” [“Courage Through History,” Jul|Aug 2020.])

Perhaps the most striking thing about the 1964–65 list is that 23 out of 25 courses fell within the liberal arts (which encompass statistics and economics), and eight of those belonged to the humanities. This would soon change. Liberal arts would continue to dominate, especially the natural and social sciences, along with the mathematics underpinning them. But even as the ratio of CAS to Wharton students had doubled between 1959 and 1964—reaching a roughly 3-to-1 relationship that has gradually drifted closer to 3.5-to-1—humanities enrollments were about to drop like a stone.

A comparison of departmental enrollments in the mid-1970s reveals some unmistakable trends—which appear to be directly traceable to shifts in degree requirements. CAS dropped its minimum humanities requirement from four courses to three, yet those fields remained popular majors. SEAS mandated seven electives within the social sciences and humanities. But at the decade’s outset Wharton overhauled the curriculum that had powered it through the 1960s, slashing English requirements from three courses to one while replacing the comprehensive (and proscriptive) liberal arts curriculum with a more flexible system requiring two courses in the natural sciences, four in the behavioral sciences, plus two more within the liberal arts and sciences that could be satisfied without taking any humanities at all.

Wharton’s stated rationale for “streamlining” the curriculum was to enable students to more easily pursue a second major (outside of Wharton) as well as a minor. Yet the plan, which also reduced the number of course credits needed to graduate from 40 to 36, sparked some faculty dissent. “Opponents of the reforms,” the Daily Pennsylvanian reported in 1973, “said they feared that given too much flexibility, students would either concentrate all their courses in business or business-related fields, or else avoid business courses whenever possible.”

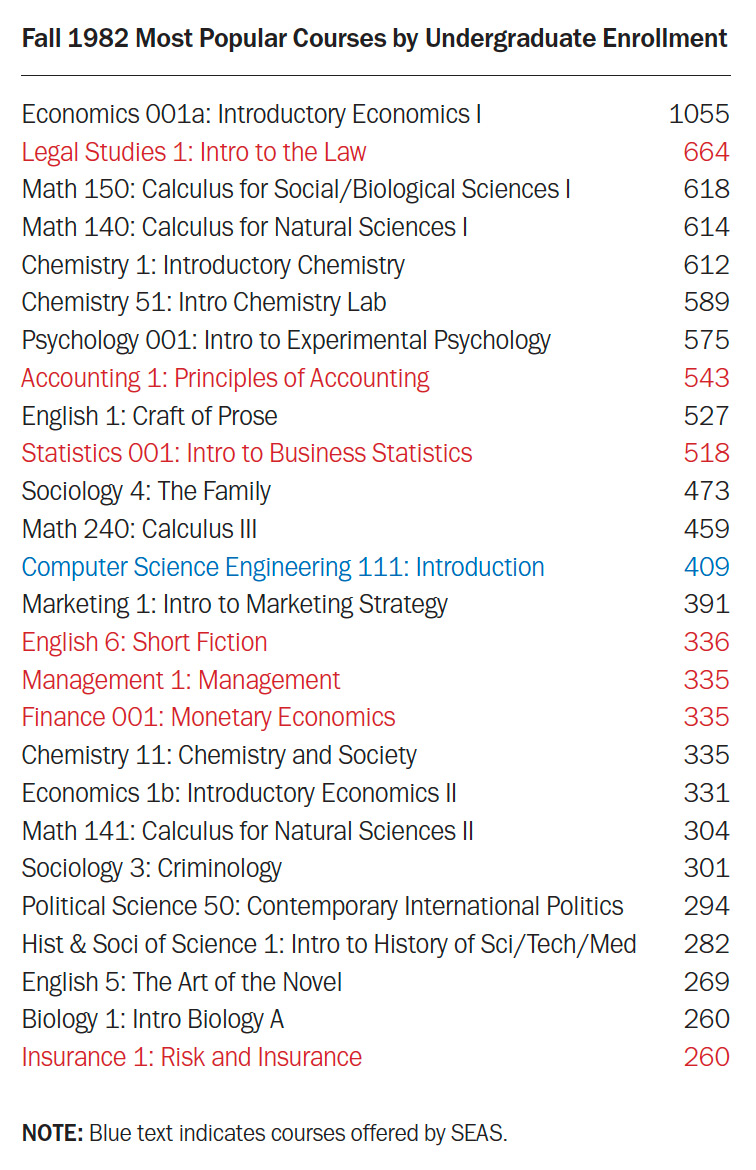

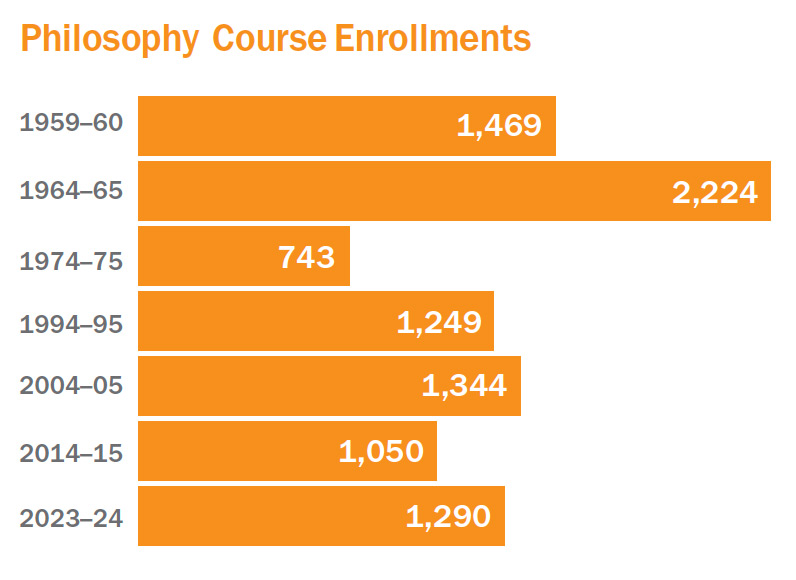

Both sides appear to have been farsighted. The 1973 reform, whose broad template remains recognizable in today’s curriculum, set the stage for a rise in Wharton double-majors. Some 28 percent of Wharton undergraduates now pursue more than one degree, and 21 percent take a minor. Meanwhile, humanities enrollments cratered. Total participation in English, Classical Studies, and Religious Studies had plummeted by 1974-75. Philosophy course enrollments fell by 65 percent. History courses initially held on, but fell precipitously between 1974 and Fall 1982, when the University registrar produced another detailed report on course enrollments.

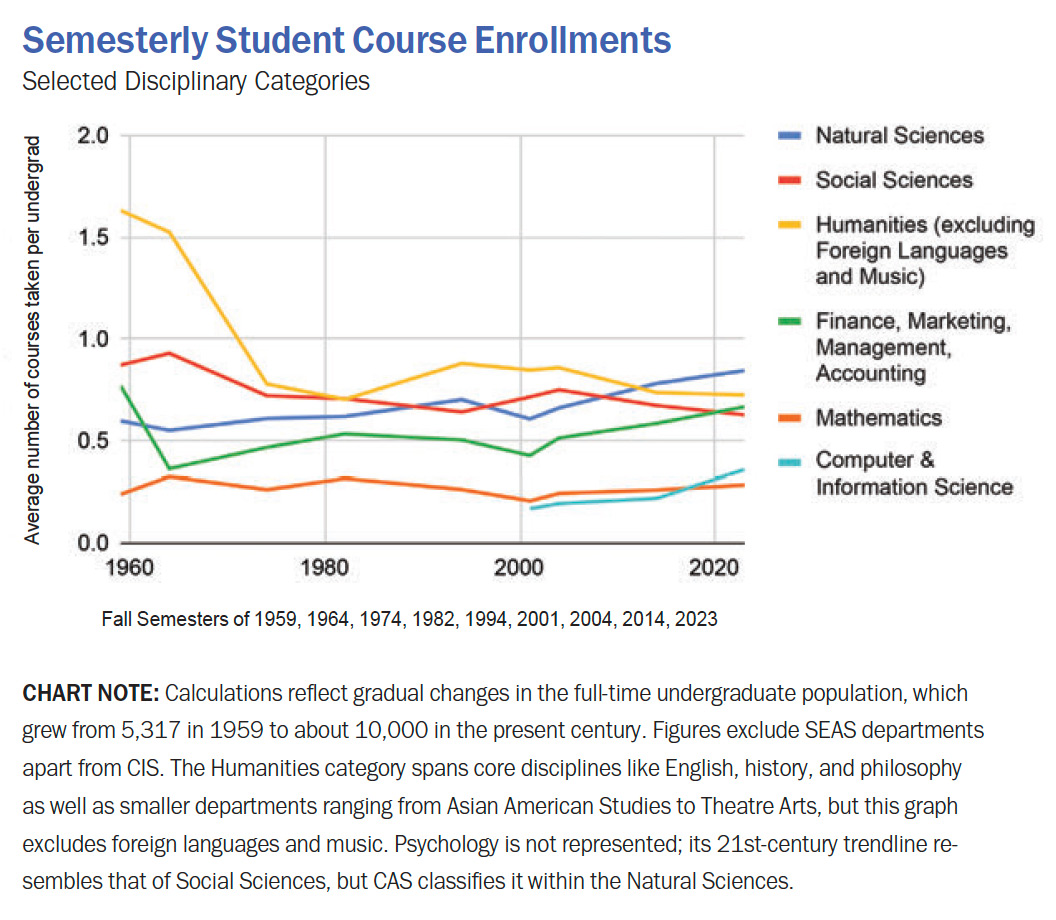

The liberal arts still accounted for the lion’s share, but the average Penn student of 1982 took fewer than half as many core humanities courses as their mid-1960s predecessors. (See chart on page 34.) The dynamic spanned all four undergraduate schools, though the rates of attrition were steepest within SEAS and Wharton. Students in those schools appeared to shift toward the social sciences to satisfy distributional requirements while all but abandoning certain humanities departments. On a per capita basis, for instance, Wharton’s history and philosophy enrollments fell by 78 and 85 percent, respectively.

Education historian Jonathan Zimmerman, the Judy and Howard Berkowitz Professor in Education in Penn’s Graduate School of Education and author of books including The Amateur Hour: A History of College Teaching in America, suggests that there’s a simple way to explain shifts like these. Namely, that students respond swiftly to curricular changes. “It may be that what we imagine as a decline in a particular discipline is really the function of some administrative decisions” around distributional requirements and the like, he observes. “And when we make these decisions, the ultimate question is always: What are the consequences for people’s education?”

This period was also marked by a wholesale drop in course enrollments, again driven by graduation requirements. In 1964, CAS curricula envisioned that undergraduates would take between 34 and 40 total course units, Wharton specified 43, and SEAS outlined the credit-hour equivalent of roughly 47 courses. By 1982, CAS and Wharton expected students to take 36 total courses, while SEAS departments mandated 40 or 41 for a Bachelor of Science in Engineering. Currently Wharton and SEAS students must take a minimum of 37 courses to graduate, while CAS students can get a diploma with between 32 and 36, depending on their major. Yet in recent decades Penn undergraduates have tended to exceed those minimums, as multiple majors and minors have become more common.

It bears noting that total enrollments, be it by course or department, are only one measure of student engagement—and not necessarily the best one. The 1975 Penn Course Guide (compiled by the Student Committee on Undergraduate Education, which wrested the publication away from the DP in 1971 and was eventually succeeded by the Penn Course Review student organization) combined increasingly detailed survey data with descriptive reviews that underscored the impact that smaller niche courses can have on individual students. English 190: Topics in Women and Literature drew only 23 takers the previous year, but some deemed it the “most stimulating course I’ve had at Penn” thanks to Nina Auerbach, “by far the best professor I’ve had at Penn” notwithstanding the “tough, heavy workload.” Other students maintained that Jack Reece’s History 546: Europe in the 20th Century (124 students) was “without question … one of the finest this university has to offer.” Just 15 undergraduates took Introduction to African American Studies, but they gave it stellar marks as a “great intellectual experience” thanks to the “brilliant” professor Houston A. Baker.

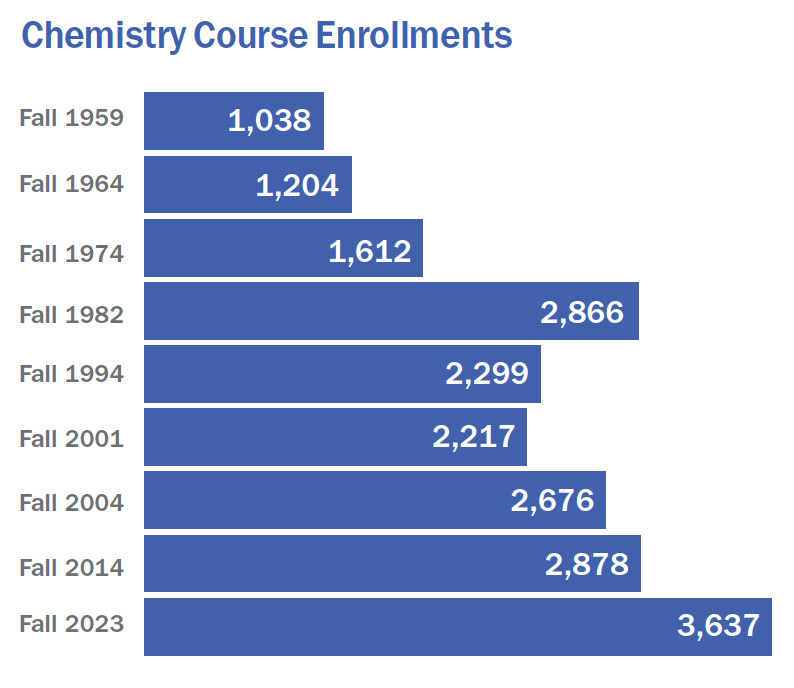

It’s also worth emphasizing some of the other ways Penn was growing during this period. For instance, the 1974–75 Course Catalogue listed 66 courses in biology and six (plus a lab) in bioengineering. By 1982, the biology department was offering 85 courses (including 225: Neurobiology and 530: Electron Microscope Techniques), while Bioengineering listed 36—sextupling in just eight years to address topics like Lasers in Medicine and Ionizing Radiation. Meanwhile SEAS listed 30 classes in computer science—28 more than it offered in 1964–65.

This was also an era of rapid growth in the University’s foreign language offerings. From a mid-20th-century baseline made up of Romance and Germanic languages, Russian, Chinese, Arabic, Hebrew, Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit, Quakers in the 1980s could try their tongues on everything from Hindi to Hausa, Armenian to Swahili, Ukrainian to Yoruba. By the early 1990s that list had expanded to include Korean, Vietnamese, Amharic, and too many others to list. Nevertheless, Penn students by and large responded to this explosion of options by piling into Spanish classrooms.

In 1964–65, more students took German than Spanish—yet both those departments combined still trailed the number of undergraduates who studied French. Spanish caught up to French in the early 1980s, and by 1994–95 Spanish enrollments doubled French ones (the linguistic runner-up). That relationship has held steady ever since, the only real change being falling enrollments in both languages over the last decade or so. The College of Arts and Sciences still mandates completing the “fourth-semester level” course in a foreign language (Wharton reduced its requirement from four to two semesters in 2017), but approximately half of today’s incoming students satisfy that by testing out of one or both years.

The dynamic evident in foreign languages—an expanding menu of courses, from which students often select a rather narrow subset—exemplifies a longstanding tendency that has occasionally sparked faculty concern. As dean of the College in the late 1980s, sociology professor Ivar Berg attempted to counteract that trend with a reform designed to promote “educational breadth.” A College study had found that students generally ignored many of the 1,700 courses then available, instead crowding into 129 popular offerings. In response, a committee replaced the three old distributional divisions—Humanities, Social Sciences, and Natural Sciences—with a requirement of 10 courses spread between six new panels: Society; History and Tradition; Arts and Letters; Formal Reasoning and Analysis; the Living World; and the Physical World. This formed the basis of the “Sectors of Knowledge” that College students must still satisfy today, later bolstered by a parallel “Foundational Approaches” distributional requirement.

Be it for that reason or some combination of others, humanities enrollments recovered significantly in the 1990s and stabilized in the early 2000s. The philosophy and history departments saw especially sharp gains, roughly doubling their course enrollments between 1982 and 2001. Alumni from the latter era may associate the rise of history with one man: Thomas Childers. The Sheldon and Lucy Hackney Professor, upon whom the Class of 2000 bestowed the Senior Class Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching by popular vote, was, per the 2001 Penn Course Guide, “an unbelievable, dynamic lecturer.” His justly famous HIST-430: The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich and HIST-431: The World at War attracted loads of students with lectures likened to “a really good TV episode.”

More common, though, were professors who attracted students in modest numbers but made deep impressions. The 135 students who took HIST-020: History of the US to 1865 gave high marks to the “absolutely brilliant” Richard Beeman, a former chair of the Department of History and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Eighty-four took ENGL-090: Topics in Women & Literature with the “inspirational” Rita Barnard, “a treasure who genuinely cares.”

In 2001 SEAS reimposed the English composition requirement it had done away with in the late 1960s, realigning with Wharton and the College in that regard. Had the schools steered all students into the same many-sectioned course, as in the mid-20th century, then English composition would have topped any list of the most popular classes. But undergraduates could instead choose from about a dozen thematic writing seminars. Today’s students can choose between roughly 30 discipline- and genre-based writing seminars offered through Penn’s Critical Writing Program (rather than the English department).

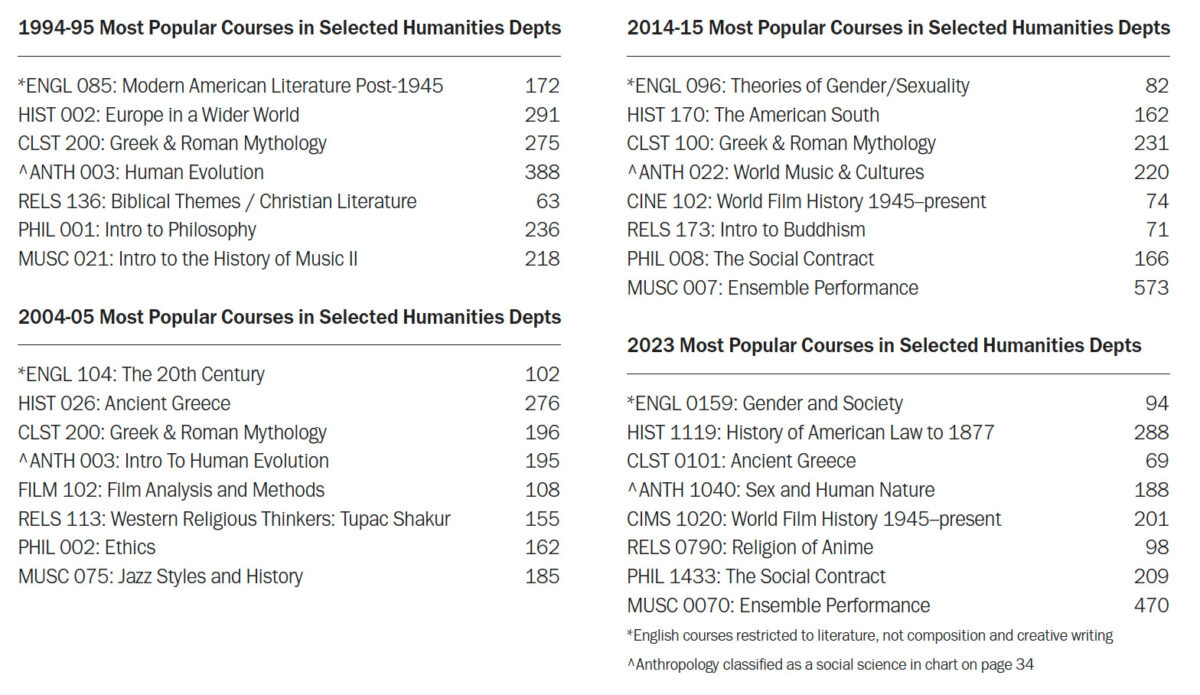

The dispersal of rising humanities enrollments across a larger number of courses meant that no single humanities course (other than Intermediate Spanish) made a top 25 list from 1994–95 onward, in the years the Gazette sampled. (An argument could be made that Wharton’s Legal Studies 101: Intro to Law and Procedure falls within the humanities—or that it is more properly regarded as a professional subject. Readers will surely make their own interpretations.)

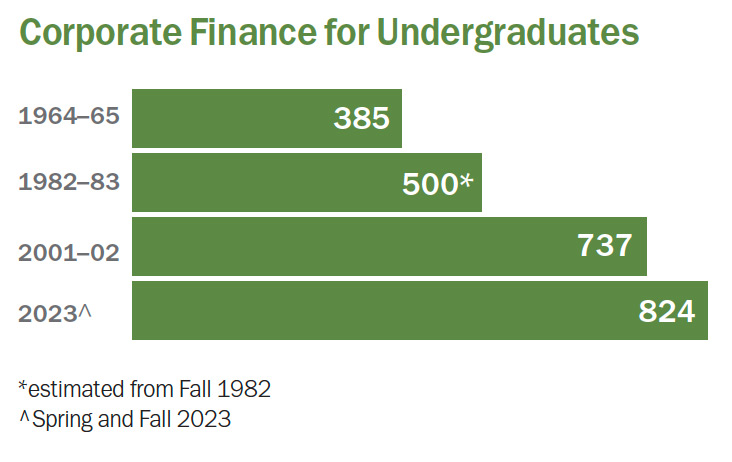

The turn of the century was also an inflection point in the relationship between liberal arts and vocational training at Penn. Wharton exemplified the trend. For decades the school had described its curriculum as offering undergraduates the chance to “take approximately 55 percent of courses in business, or up to 70 percent in liberal arts.” By 2001–02, this longstanding phrase had been removed from the course bulletin, which now specified a business-heavy program supplemented by a writing seminar; seven courses in the liberal arts categories of Social Structures; Language, Arts, and Culture; and Science and Technology; plus two more non-business electives that could be taken pass/fail. No student who took 70 percent of their courses in the liberal arts could come close to satisfying the business requirements.

In 1994–95, nine of the 10 most popular courses were classic liberal arts—biology, chemistry, math, foreign language. That dropped to seven in 2004–05. By 2014–15 six of the top 10 slots were occupied by pre-professional offerings from Wharton.

(No registrar course enrollment reports could be found in the Penn Archives from after 1990, so data for subsequent years derive in part from enrollment statistics collected by Penn Course Review, which became a web-only resource in 2002. In its digital incarnation run by the Penn Labs student group, the Review sadly no longer features written comments about courses and professors, which had previously been collected and edited by the now-defunct Penn Course Review student club. But it does feature ratings on the traditional 1 to 5 scale along with detailed enrollment data going back to 1994–95. The University registrar’s office declined to assist the Gazette, referring us instead to individual schools and departments whose responsiveness and data-reporting conventions varied widely. All figures from 1959 to 1982 are definitive, as are CAS and Computer & Information Science figures from 1994 and later; Wharton figures depend solely on Penn Course Review data, however, which are prone to specific errors. Painstaking efforts have been made to correct for data eccentricities stemming from courses with multiple teachers or cross-listed in multiple departments, but occasional mistakes may remain—albeit chiefly among less-popular courses whose enrollments would have minimal impacts on the trends observed.)

Top 10 and 25 lists have shortcomings. At Penn, for instance, they arguably overstate the centrality of certain courses within Wharton, whose undergraduates share many more requirements than College students who choose from among more than 60 majors and 160 concentrations. Yet departmental comparisons over time reveal some equally dramatic shifts. In 1964–65, for instance, physics classes drew more than three times as many students as marketing classes. Now they’re neck and neck. Undergraduate finance enrollments, which were less than one-third of math enrollments, have nearly pulled even. History enrollments have roughly halved since 2001–02 and are now far eclipsed by management enrollments, which have almost doubled. Classical Studies and philosophy staged stirring comebacks in the late 20th century and have held more or less steady since then. Cinema & Media Studies enrollments have more than tripled during the 21st century, while fewer students seek out courses focusing on English-language literature. Department of Comparative Literature enrollments have roughly doubled this century, but virtually no one wants to read Shakespeare for homework anymore. In 2001–02, six courses with Shakespeare in the title collectively drew 293 students. In the fall and spring of 2023, four courses whose descriptions referenced the Bard attracted a grand total of 49.

No department has witnessed a sharper rise in interest than SEAS’s Computer and Information Science (CIS). In 2017 the Daily Pennsylvanian reported that computer science majors had more than tripled over the previous 10 years, from 250 to 800. And non-majors were clamoring to enroll in CIS classes in even higher numbers. Sampath Kannan, the Henry Salvatori Professor who was then chair of the department, told the newspaper that 40 percent of Penn’s undergraduate population took at least one CIS course before graduating. In 2018, the DP reported that “painfully high” demand for CIS courses was leading to waitlists that were in some instances twice as large as the enrollment capacity of certain classes. Figures provided by current CIS senior director of academic affairs Lee Dukes show that the department’s undergraduate course enrollments have nearly quintupled since 2004–05. In the spring and fall of 2023, College students accounted for about 27 percent of the total and Wharton undergraduates made up another six percent.

Overall, humanities enrollments have drifted downward this century after peaking sometime around 2004–05. Data provided by the College of Arts and Sciences indicate a roughly 14 percent drop in enrollments spanning all humanities disciplines over the last 20 years. Attrition has been concentrated in CAS; thanks in part to mandatory writing seminars, Wharton and SEAS humanities-related enrollments have remained steadier over that stretch. (Opinions are bound to differ over whether classes like Writing Seminar in Physics or Writing Seminar in Statistics should be grouped under humanities. For the purposes of this article, they are, primarily to facilitate comparisons to the 20th century, when mandatory composition courses were taught within the English department. But this almost certainly understates the magnitude of the humanities’ drop-off.)

Some critics of elite universities blame declining humanities majors and enrollments on the proliferation of courses that filter subjects through the prisms of gender studies, critical race theory, intersectionality, and the like. (Other critics celebrate the decline for much the same reason.) But this argument is difficult to sustain based on Penn’s course catalogue, or the classes that reliably attract students year in and year out. A postmodern or progressive sensibility is evident in a fair number of English department offerings; and a small handful of Religious Studies classes have used departmental cross-listings, contemporary pop cultural glosses, and/or star professors to lure students (notably Michael Eric Dyson’s Spring 2005 blockbuster RELS-113/AFRC-113: Western Religious Thinkers: Tupac Shakur). But a survey of the most popular courses in core humanities departments turns up titles that by and large would have been familiar 50 years ago—only they tend to draw smaller crowds now.

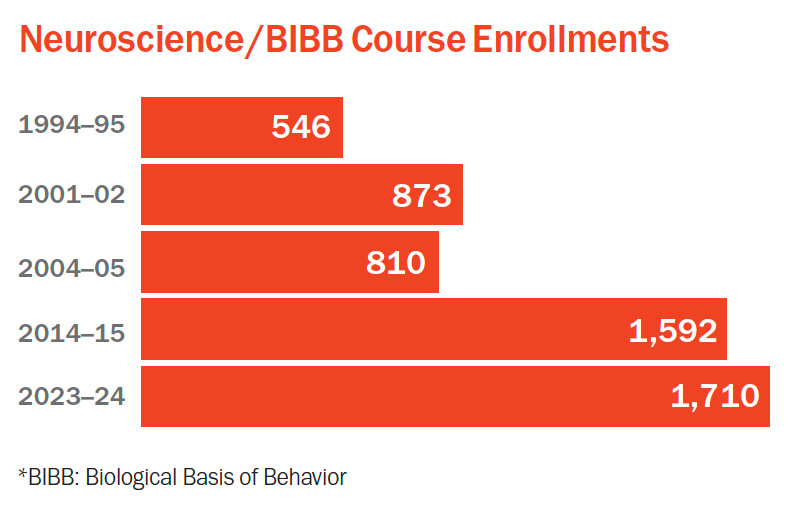

The College’s data suggest another explanation for falling humanities enrollments among CAS students: they have flocked to the natural sciences. CAS students currently enroll in 44 percent more natural science classes than they did in 2001–02. So even as natural science enrollments have fallen seven percent among Wharton students and 10 percent among SEAS students, Penn has seen a 27 percent increase in the undergraduate study of natural sciences overall—driven in part by burgeoning fields like neuroscience. The social sciences have fared less well. These disciplines draw four percent fewer College students than at the century’s outset, while enrollments have fallen 27 percent among SEAS undergrads and collapsed by 59 percent for Wharton.

Ultimately, top 25 lists and departmental comparisons alike tell much the same story as on-campus recruiting trends and post-graduation job data: Penn prepares many students for careers in healthcare, technology, engineering, law, and the like—while over the last 20 years few fields have seemed to lure contemporary Quakers quite like the prospect of finance and consulting. A 2023 Penn Career Services survey found that nearly half of Class of 2022 respondents pursuing full-time employment had taken jobs in one of those two fields. That included nearly 80 percent of Wharton grads and 47.5 percent of CAS grads—a pattern that held up for majors in disciplines as different as philosophy, physics, political science, biology, and Classical Studies.

Any number of dynamics can be discerned in these data, but you’d have to squint pretty hard to see a rash of woke indoctrination. So it’s no surprise that many Penn faculty tend to worry about something else: the proportion of undergraduates whose career anxieties work against the horizon-broadening spirit that has long been the distinguishing feature of a liberal arts education.

“We want our students to have a breadth of education—that’s always the point,” says Peter Struck, the longtime Classical Studies professor and director of both the Benjamin Franklin Scholars and Integrated Studies programs who became the Stephen A. Levin Family Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences in August [“Gazetteer,” Nov|Dec 2024]. “Twenty years ago, when we last redid the general education requirement, there was a strong push to make sure students were taking enough STEM. So we succeeded in that,” he notes.

Now the College is revisiting those distributional requirements in a process Struck foresees taking two or three years and hopes will strike a new balance that bolsters the humanities.

Chart

“Absolutely, it’s important that you be numerate—that you understand data and how it works, and you understand the sciences. It would be foolish to send students out in the world soft-pedaling that,” he says. “But you’re going to be at a great disadvantage if you’re not also literate. You need to understand how to read, how to argue, how to understand conflicting evidence that you get in these kinds of complex texts. [Because] when problems come your way, they don’t look like problem sets. They don’t look like lab writeups. When problems come your way, they’ve got many dimensions. Some of them will be susceptible to a solution through data, but a lot of them are going to require interpretive work, which is the kind of thinking that we use in the humanities all the time. Lots of them are going to require you to understand culture and its legacy and its history and where people are embedded.”

Selling that idea circa 2025 is bound to require sensitivity to the cultural context in which today’s Penn undergraduates are themselves embedded.

“We’re in a different time than we were 20 years ago. Our students are also different,” Struck observes. “And I don’t just mean that they’re all on social media, although they are—so that’s one thing—but they’re different demographically. Twenty years ago, about 80 percent of them came from a kind of uniform cultural background. It was anchored in the upper echelons of the American aristocracy. We still have an extraordinarily talented undergraduate student body, but they’re much more diverse.”

Their economic diversity may be as salient as their cultural diversity. According to Penn’s admissions department, 20 percent of the Class of 2027 qualified for Pell grants. A great many more are acutely attuned to the financial burden their education entails. Tuition, fees, and room and board have more than doubled over the last two decades; the 2024–25 all-inclusive sticker price is $87,860. Even students who receive relatively generous financial aid packages are excruciatingly aware of the sacrifices their families make to send them to college.

“If you’re coming from a background like that,” Struck says, “and a professor in your English class or your history class is sort of tone deaf to your worry about what you’re going to be doing after college—because there might be an urgent need to make sure that things are well taken care of financially with respect to your parents and everyone that you love and people that are investing deeply in you to go do this thing—well, that pressure was different 20 years ago, when the students were more likely to be from very well-heeled backgrounds and in fact their futures were going to be secure.

“So we can’t just assume anymore that what college is supposed to be has been acculturated for generations into our student body—and that the value of humanities just goes without saying,” he adds. “We need to say it, and we need to talk about it, and I want the curriculum to reflect the importance of all of these different modes of thinking.”

Perhaps surprisingly for someone who has devoted his life to the pursuit of “ideas for their own sake,” Struck embraces a somewhat pre-professional attitude as a lever to restore faith in the liberal arts project in general and humanities scholarship in particular.

“That career anxiety of theirs, is my anxiety. I need to co-own that with them,” he declares. “I need to help them with it. It’s part of what an education is going to be for the students that we’re with right now. And if we don’t do that, I think we’re dropping the ball.

“In the current environment, one of the things we’re trying to address is that there’s a misimpression among the students—that runs deep and that’s hard to dislodge—that majoring in the humanities is not a good career move. This is not true,” he says, pointing toward the ranks of CEOs who majored in fields like history, literature, and Classical Studies (a list that includes Apple’s Steve Jobs, YouTube’s Susan Wojcicki, Hewlett-Packard’s Carly Fiorina, Walt Disney’s Michael Eisner, and Chipotle’s Steve Ells, among others).

“We have to do a much better job of linking what they’re doing here to what they’ll do next—and also pushing back against the idea that the major courses of study that don’t seem to give very specific skills that are applicable to specific professions, that those are somehow taking you sideways. Because that’s just not the case. In fact, they’re preparing you not just for that first job out of college, but for a lifetime of leadership in your community, embeddedness in your community, and also in your professions.

“Rigorous thinking doesn’t go out of style,” he concludes. “It doesn’t go out of date. But this or that method of computer programming that you’re going to learn today will go out of date. I can guarantee that. I learned C++ [programming language] when I was in high school, and that’s going the way of the dodo. Focusing in on specific skills is something all of our graduates will do their whole lives. But doing the hard work of learning how to think, within your liberal arts degree, makes you a much more efficient acquirer of skills as you move through your life. And if you don’t take care of that now, there aren’t a lot of opportunities to do it later in your life. That’s the core of what we’re doing in liberal arts.”

And yet as the last 65 years have shown, the boundaries and emphases of a liberal arts education are not fixed. Times change, knowledge grows, and curricula must adapt. And every time a university is moved to renew its mission in this way, it makes an unavoidable declaration. “You know, a curriculum is not just a bunch of courses,” reflects Jonathan Zimmerman, who has been tapped to help shape the next iteration for the College. “It’s a set of statements about what you value, and what you think an educated person is.”