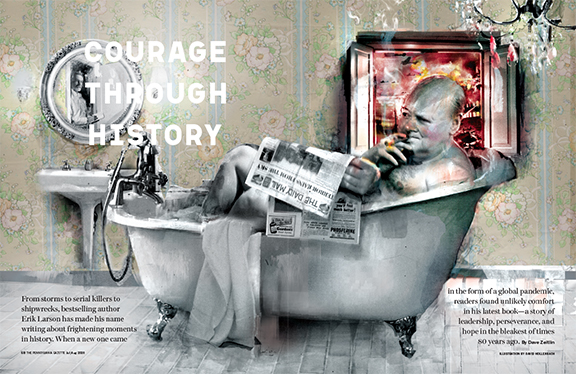

From storms to serial killers to shipwrecks, bestselling author Erik Larson has made his name writing about frightening moments in history. When a new one came in the form of a global pandemic, readers found unlikely comfort in his latest book—a story of leadership, perseverance, and hope in the bleakest of times 80 years ago.

By Dave Zeitlin | Illustration by David Hollenbach

Plus: Excerpt from The Splendid and the Vile by Erik Larson

It was dusk in London when Erik Larson C’76 gazed out of his Egerton House Hotel window. The sky was clear, the weather warm—the kind of evening that would have been perfect for hundreds of Luftwaffe aircraft to suddenly appear on the horizon and pummel the city with bombs.

How terrifying must that sight have been? How did ordinary British citizens mentally cope with relentless air raids for 12 straight months from 1940 to 1941? Or with the more terrifying belief that Hitler would soon unleash a full-on invasion with German paratroopers landing in the heart of one of the world’s great cities?

Larson, a bestselling author known for his gripping works of historical narrative nonfiction, tried to imagine those feelings while in his hotel room that beautiful night two years ago. He did the same during daytime walks through London’s famed Hyde Park. “Suddenly you’re vibrating with a sense of the past,” he says. “And that’s what I try to convey to my readers—that sense of immersion in an era, in a story, to the point where maybe they lose sight of the fact that they actually know how it ends.”

How World War II ends is, of course, well known. The Nazis never invaded Great Britain and instead got bogged down in the Soviet Union, the United States entered the war after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the Allies ultimately prevailed. But before all that, the only thing that stood in Hitler’s way was the United Kingdom and its pugnacious prime minister, Winston Churchill—a man who, despite his faults, Larson says, was a “terrific leader for this particular period, because he was very good at helping people find their courage.”

Although, by Larson’s admission, Churchill is “one of the most heavily written-about people in the history of the planet,” his newest book, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz, delves into the prime minister’s first year in office—which coincided with the German air campaign meant to bring Great Britain to its knees.

Drawing on original archival documents, untapped diaries, and recently released intelligence reports, Larson approached Churchill from a different angle, painting a vivid portrait of what life that year was like on a daily basis for the prime minister and his family, including vivacious daughter Mary, and an inner circle of advisors. A diary entry from one of those advisors, Churchill’s private secretary John Colville, turned out to be the inspiration for the book’s title. During one of the raids, while watching shells explode and fires rage underneath a clear black sky from his bedroom window, Colville “was so struck by the sort of weird juxtaposition, as he put it, of natural splendor and human vileness,” Larson says.

That kind of juxtaposition animates Larson’s book. During the day, Londoners still went to work, shopped in stores, ate in restaurants, sunbathed in parks—but they did so while holding onto gas masks and “their identity discs, in case they got blown to smithereens,” Larson says. Then, at nightfall, they darkened their windows, went to their basements, bedrooms, or backyard “Anderson shelters,” and hoped luck was on their side when the bombs dropped. “As time wore on,” Larson says, “people just said, ‘Look, I can’t predict whether I’m going to live or die. There’s not much I can do about it, so I’m just going to live my life.’”

Released in late February, shortly before cities around the world were flipped upside down due to the novel coronavirus outbreak, The Splendid and the Vile quickly found its audience. Larson says he hears “all the time” from people who tell him they’ve found comfort reading the book while quarantined at home, drawing hope from how people in England 80 years ago strove for normalcy in the midst of terror and uncertainty. “I’m slightly mystified,” he says. “People are turning to this book about mass death and chaos for solace, and they’re finding it. They’re finding it because there is this model of really terrific leadership. And I think people need to be reminded of what leadership looks like.” Also, Larson notes, the story does have a happy ending—even if nearly 45,000 Britons lost their lives in the air raids. “They got through it,” he says. “They went through the gates of hell and came back out again.”

Has the story of “The Blitz” even helped Larson, who’s known by his three adult daughters as the “Prince of Anxiety” because he’ll text them “Dad Alerts” if it’s a windy day or there’s ice on the ground? Had he been alive in London in 1940, he admits he probably would have been a “drooling mass of quivering anxiety” at first. But eventually, he says, “I’d like to think I would rise to the occasion. I think one becomes emboldened if one sees people around them being courageous.”

Thinking some more about how Churchill taught the British people what Larson refers to as “the art of being fearless”—and how important it is today to come together again, during a global pandemic—he adds another thing:

“I feel courage is infectious.”

Larson has found different kinds of courage throughout his life, making decisions both impulsive and risky to go from what he calls a “shiftless, haphazard guy” to an author whose five books before Splendid have collectively sold more than nine million copies worldwide.

Undecided about where to go to college, the Long Island native settled on Penn because that’s where his girlfriend was going. They broke up soon after arriving on campus, but he had a good time anyway. As a freshman, he was “transfixed” by a Russian history class taught by the late Alexander Riasanovsky, a longtime University faculty member and, notes Larson, “an exiled Russian prince.” One night, Larson says, Riasanovsky came to a campus party to “teach us how to drink vodka the Russian way.” It was a different time, he laughs, adding, “I will tell you that I’ve never been drunker in my life.”

Riasanovsky turned Larson on to Russian history and literature, which he studied the rest of his time at Penn. He had other great history professors too—so much so that he wanted to become one himself for a while. He also thought that he’d like to become a prosecutor, or maybe a New York City cop. “I went in thinking I was going to do one thing with my life, left thinking I was going to do another, and did neither of those,” he says.

Writing, he says, “was always sort of my background thing.” When he was 13, he wrote a novella that mirrored the Nancy Drew books he liked to read growing up. At Penn, he kept writing, but not much that was published—mostly short stories and “failed novels” in between schoolwork and vodka drinking lessons. Another memorable Penn course taught him to appreciate Ernest Hemingway, whose writing style—“in terms of clarity and simplicity and the conservation of words”—became a lifelong resource.

After college, he got a job as an editorial assistant at a publishing company in New York, but it was a trip to the movie theater that proved most formative. Upon seeing All the President’s Men, the 1976 political thriller about the Watergate scandal, he “decided then and there, this is what I wanted to do with my life—I wanted to bring down presidents.” His wish to become the next Woodward or Bernstein was short-lived, but it did lead him to the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism, then to the Bucks County Courier Times in suburban Philadelphia. “I was not a natural reporter,” he says, but he tried his hand at longform investigative features on top of the daily grind of covering cops and laying out the newspaper. After being passed over for a promotion, he shopped his résumé around and in 1980 landed at the Philadelphia bureau of the Wall Street Journal.

From Philly, he accepted a transfer to San Francisco, where he sought out light, funny things to write about, “always finding better ones than the rest of us,” says Carrie Dolan, a friend and former colleague. Dolan figured Larson would move on to “great glory,” but given what she knew about him, “thought he’d write funny stories or mystery novels.” Larson wasn’t sure about his career trajectory either when, in 1985, the Journal’s managing editor offered him the Atlanta bureau chief’s job and Larson told him that not only was he declining the promotion, he’d be leaving the paper entirely.

After Larson married a neonatologist named Christine Gleason, whom he had met on a blind date in San Francisco, the couple moved across the country to Baltimore, where she started a new job at Johns Hopkins. There he did some freelance magazine writing, raised his three daughters with his wife, and in 1994 published his first book: The Naked Consumer: How Our Private Lives Become Public Commodities. A collection of essays about how companies were spying on individual consumers, “I thought it was going to be a huge bestseller,” he says. “And nobody bought or read it. But I did get the bug, and I loved the process. I loved the pace. It suited my personality.”

His next book, Lethal Passage: The Story of a Gun, was about the country’s gun culture, following one model of a handgun and using the life and experiences of a school shooter to frame it. Though not a bestseller, that book did better than the first, and perhaps more importantly, helped him determine that the secret to his success might be rooted more in narrative storytelling than hard journalism.

So he went to the library, took out the Encyclopedia of Murder, and went down several rabbit holes in search of the wildest damn stories he could find.

By the time his sixth or seventh book proposal was rejected, Larson was getting ready to dump his literary agent, David Black. Looking back on it more than 20 years later, the author is glad he didn’t. In fact, he credits Black with helping him shape the narrative arc of a story of a hurricane that struck Galveston, Texas, in 1900. The result (after the eighth proposal was finally accepted, and a publisher found) was Larson’s 1999 breakthrough book: Isaac’s Storm: A Man, A Time, and the Deadliest Hurricane in History. “What was clear from the very beginning,” recalls Black, still Larson’s agent today, “was that he had something really special that he was working on.”

Finding the idea for the book wasn’t exactly a straight line either. It can be traced back to 1994 when Larson read Caleb Carr’s The Alienist. Though it was a novel, Larson was fascinated by the real-life characters set in 1890s New York and the serial killer genre. So he thought maybe he’d like to try to write about a real-life murder.

Very quickly in his research digging through The Encyclopedia of Murder, he came across serial killer H. H. Holmes, who would go on to become one of the two central characters in his next book, the monster hit The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair That Changed America. But at the time, he says, “I didn’t want to do crime porn, and he was too over-the-top bad.” Instead, he homed in on the murder of a Texas businessman named William Marsh Rice, which led him to Galveston, where he was amazed to learn of the destruction caused by the hurricane the same year Rice was killed. So he thought: Forget about the murder for now.

While digging for information about the storm at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration library, he pulled out a dusty leather binder and found a newspaper article written by the US Weather Bureau meteorologist Isaac Cline, “in which he said that no storm could ever do serious damage to the city of Galveston,” shortly before the storm killed as many as 10,000 people in Galveston alone. Just like that, his antihero was born. And Isaac’s Storm—what he refers to as his first work of narrative nonfiction—was critically well received. (It also remains his wife’s favorite, 20 years and five other books later, as hard as he tries to unseat it.) The New York Times, in its book review, called it a “richly imagined and prodigiously researched” book that “pulls readers into the eye of the hurricane, and into everyday lives and state-of-the-art science. It is a gripping account, horridly fascinating to its core, and all the more compelling for being true.”

Of all the “horridly fascinating” events and people through history, H. H. Holmes—American’s first modern serial killer—would rank high on any list. After Isaac’s Storm was published, Larson remembered a reference made to the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 in something he had read about Holmes, and was drawn back in. He submitted what Black calls a “stunning” proposal that weaved together two parallel storylines—one on Holmes building his hotel of horrors and the other on the architect Daniel Burnham leading the design of the fairgrounds just blocks away.

Devil in the White City went on to win the Edgar Award for best fact-crime writing, was a finalist for the National Book Award, and is now being developed as a Hulu series with Leonardo DiCaprio and Martin Scorsese attached. But on the night before it was published in 2003, Larson was convinced his career was over. “I thought it was going to crash and burn,” he says, unsure of how critics would react to one book with two distinct storylines that rarely intersect.

Instead, many marveled at how a work of nonfiction could feel so much like a novel, and how something like the invention of the Ferris Wheel could be almost as suspenseful as Holmes wooing and torturing his victims. “I knew that was going to be either the biggest thing ever, or people would be like, ‘What is this guy thinking?’” laughs Dolan.

Although Devil proved to be a “really amazing thing in terms of my life and my career,” Larson notes it didn’t make it any easier to find or sell his next book. “Being of Scandinavian origin,” he says, “I’m a pessimist at heart.” He once again went the dual storyline route for the 2006 book Thunderstruck, which is about a criminal chase and the parallel careers of wireless inventor Guglielmo Marconi and serial killer Hawley Harvey Crippen. “Right away, people were assuming, ‘Oh, this is Erik’s shtick,’” he says.

It wasn’t. Following Thunderstruck, his next three books—In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin (2011), Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania (2015), and Splendid—didn’t rely on dual storylines and were about subjects more widely known. What did remain the same, however, was the novelistic feel of his historical explorations. It’s a testament to his writing skills, but the real reason he’s able to do that is because of his “extraordinary attention to detail and his extraordinary amount of research,” Black says. “We thought we knew about the Lusitania. We didn’t. We thought we knew about the coming of the Nazis in 1939. We didn’t. We thought we knew everything there was to know about Winston Churchill. We didn’t.”

For Larson, hunting for new things about old subjects, in far-flung archives and libraries, “is the fun part” of the process—which, aside from more overseas travel, hasn’t changed much over the last two decades. That’s why he’s never employed a research assistant to help.

“I don’t know what I’m looking for,” he says. “But I know exactly when I find it.”

Before deciding to write a book about him, Larson didn’t have a “deep abiding interest in Winston Churchill,” he admits. “He was actually, believe it or not, an afterthought in the idea process.”

The book’s roots can be traced to a recent move he and his wife made to Manhattan from Seattle (where they had lived for a couple of decades after Baltimore). Upon arrival, he thought about what 9/11 must have felt like for New Yorkers—the smoke, the sirens, the shock—versus what it was like for him watching the horror unfold on CNN, nearly 3,000 miles away. Then he thought about another major city attacked from the sky—and how The Blitz began with 57 consecutive nights of bombings. Or, as Larson puts it, “57 consecutive 9/11s.”

Initially, he thought it could be powerful to follow a typical London family during this time of incessant fear and horror. “Then I thought, Wait a minute, why don’t I do the quintessential London family?” So that’s how one of the most influential historical figures ever became the centerpiece of the story.

Larson had no way of predicting it, but Churchill’s World War II leadership would come into sharper focus just as his book was released. As various world leaders struggled to prepare for and respond to the global pandemic, it seemed many people longed for someone known to inspire and motivate in a time of crisis. Yet while Churchill might be best known for his “rousing bits of rhetoric that we’re all familiar with,” Larson points to his honesty at the beginning of those eloquent speeches as one reason why he was such a steady hand. “What Churchill was very good at doing,” the author notes, “was giving a sober assessment of the situation without sugarcoating it, but then following with real grounds for optimism.” (For Larson, that presents the most glaring contrast with American political leadership in the age of the coronavirus.)

Churchill’s bravery was unmatched, too. Despite increasing fears for his personal safety, “no raid was too fierce to stop him from climbing to the nearest roof to watch,” Larson writes in Splendid. “Even near misses seemed not to ruffle him.” That combination of fearlessness and honesty made his frequent visits to bombing sites to speak directly to English citizens “a very powerful thing for the public,” Larson says. “They knew he was with them. They knew he was moved. And they knew he was hell-bent on doing something about it.”

The book also captures Churchill’s delicate diplomatic balancing act in his frequent correspondence with US President Franklin Roosevelt. And it includes chapters from the Nazi perspective, showing how Hitler’s brazen confidence in swift English capitulation slowly diminished as the UK’s Royal Air Force (RAF) fought back the Luftwaffe and waged bombing campaigns of their own on German cities. Near the end of The Blitz in May 1941, Larson recounts a diary passage from the Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels that said of Churchill: “This man is a strange mixture of heroism and cunning. If he had come to power in 1933, we would not be where we are today. And I believe he will give us a few more problems yet.”

Perhaps the most poignant portions of the book, though, are less about war strategy and more about the daily horrors of ordinary British citizens. Mostly using diaries that had been collected by the Mass-Observation social research organization, which he calls “the most amazing reservoir of compelling material,” Larson depicts cinematic details from the ground when The Blitz began on September 7, 1940 (see accompanying excerpt). “For Londoners, it was a night of first experiences and sensations,” he writes. The sound of a bomb crashing to the street. The skies glowing red. Billows of dust engulfing the city. “Survivors exiting ruins were coated head to toe as if with gray flour.”

The following day was just as dreadful, as people dug through the wreckage and saw corpses for the first time. But as time went on, many learned to live with it. Despite the foreboding of possible Nazi rule, Mary Churchill—who Larson calls “incredibly articulate” and “an astute observer”—still longed for love. In her diary, which Larson notes only he and one other scholar have ever been granted permission to see, “she talked about war events. But she also talked a lot about her personal life and just the normalcy of it and the fun and snogging with RAF pilots.” One particularly harrowing chapter recounts her arrival at Café de Paris just after a bomb fell on the club, killing at least 34 people, including the musician Snakehips Johnson.

“The raids generated a paradox: The odds that any one person would die on any one night were slim, but the odds that someone, somewhere in London would die were 100 percent,” Larson writes. “Safety was a product of luck alone. One young boy, asked what he wanted to be when he grew up, a fireman or pilot or such, answered: ‘Alive.’”

For the vast majority of people, it’s likely that the unease felt during a pandemic doesn’t compare to what the British had to endure during The Blitz. After all, says Larson, “we’re not going to have a bomb fall on us in the middle of the night while we’re sleeping.” But there are similarities, from minor things like toilet paper shortages to grander ideas like uniting to defeat a common enemy. “In London at that time, everybody had to pull together,” Larson says. “We have to pull together now. Everybody has to do this to get this virus to subside, or we’re screwed.”

If a leader like Churchill were alive today, Larson believes we might have an easier time finding that kind of solidarity—and also, perhaps, do a better job putting the pandemic into historical context. That, Larson notes, was another one of Churchill’s greatest strengths. “He was such a student of history,” the author says, “that he understood that this was a moment in time that had come and would go, and that it was one moment in this grand epoch of British history. And he helped make people feel like they were part of that epoch.”

Like everyone, Larson has been trying to adjust to being part of a new epoch. He’s been monitoring his anxiety with his now-retired wife at their place in the Hamptons, working on his next book proposal and doing more livestream interviews. His study of Churchill has helped him. Oreos and red wine have too. And yet, “of course there’s always going to be something that shakes your resolve, and you want to just crawl into a closet and whimper,” he says.

“But then you’ve got to dust yourself off and do the Churchill thing and come on back out.”

On a Quiet Blue Day

Life in London was normal and picturesque—until bombs fell from the sky at teatime.

The day was warm and still, the sky blue above a rising haze. Temperatures by afternoon were in the nineties, odd for London. People thronged Hyde Park and lounged on chairs set out beside the Serpentine. Shoppers jammed the stores of Oxford Street and Piccadilly. The giant barrage balloons overhead cast lumbering shadows on the streets below. After the August air raid when bombs first fell on London proper, the city had retreated back into a dream of invulnerability, punctuated now and then by false alerts whose once-terrifying novelty was muted by the failure of bombers to appear. The late-summer heat imparted an air of languid complacency. In the city’s West End, theaters hosted twenty-four productions, among them the play Rebecca, adapted for the stage by Daphne du Maurier from her novel of the same name. Alfred Hitchcock’s movie version, starring Laurence Olivier and Joan Fontaine, was also playing in London, as were the films The Thin Man and the long-running Gaslight.

It was a fine day to spend in the cool green of the countryside.

Churchill was at Chequers. Lord Beaverbrook departed for his country home, Cherkley Court, just after lunch, though he would later try to deny it. John Colville had left London the preceding Thursday, to begin a ten-day vacation at his aunt’s Yorkshire estate with his mother and brother, shooting partridges, playing tennis, and sampling bottles from his uncle’s collection of ancient port, in vintages dating to 1863. Mary Churchill was still at Breccles Hall with her friend and cousin Judy, continuing her reluctant role as country mouse and honoring their commitment to memorize one Shakespeare sonnet every day. That Saturday she chose Sonnet 116—in which love is the “ever-fixed mark”—and recited it to her diary. Then she went swimming. “It was so lovely—joie de vivre overcame vanity.”

Throwing caution to the winds, she bathed without a cap.

In Berlin that Saturday morning, Joseph Goebbels prepared his lieutenants for what would occur by day’s end. The coming destruction of London, he said, “would probably represent the greatest human catastrophe in history.” He hoped to blunt the inevitable world outcry by casting the assault as a deserved response to Britain’s bombing of German civilians, but thus far British raids over Germany, including those of the night before, had not produced the levels of death and destruction that would justify such a massive reprisal.

He understood, however, that the Luftwaffe’s impending attack on London was necessary and would likely hasten the end of the war. That the English raids had been so puny was an unfortunate thing, but he would manage. He hoped Churchill would produce a worthy raid “as soon as possible.”

Every day offered a new challenge, tempered now and then by more pleasant distractions. At one meeting that week, Goebbels heard a report from Hans Hinkel, head of the ministry’s Department for Special Cultural Tasks, who’d provided a further update on the status of Jews in Germany and Austria. “In Vienna there are 47,000 Jews left out of 180,000, two-thirds of them women and about 300 men between 20 and 35,” Hinkel reported, according to minutes of the meeting. “In spite of the war it has been possible to transport a total of 17,000 Jews to the south-east. Berlin still numbers 71,800 Jews; in future about 500 Jews are to be sent to the south-east each month.” Plans were in place, Hinkel reported, to remove 60,000 Jews from Berlin in the first four months after the end of the war, when transportation would again become available. “The remaining 12,000 will likewise have disappeared within a further four weeks.”

This pleased Goebbels, though he recognized that Germany’s overt anti-Semitism, long evident to the world, itself posed a significant propaganda problem. As to this, he was philosophical. “Since we are being opposed and calumniated throughout the world as enemies of the Jews,” he said, “why should we derive only the disadvantages and not also the advantages, i.e. the elimination of the Jews from the theater, the cinema, public life and administration. If we are then still attacked as enemies of the Jews we shall at least be able to say with a clear conscience: It was worth it, we have benefited from it.”

The Luftwaffe came at teatime …

Excerpted from THE SPLENDID AND THE VILE by Erik Larson. Copyright © 2020 by Erik Larson. Excerpted by permission of Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.