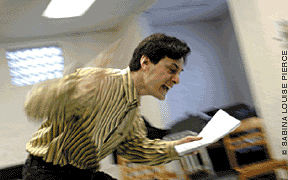

It’s a dreary Friday afternoon in late February, but in the basement of the Music Building on 34th Street, the finale of the Brahms Horn Trio is off to an exhilarating start. The concert is in two days, and coach David Yang C’89 GAr’92, Penn’s director of chamber music, is in his students’ faces: singing, yelling, and dancing. After 37 energetic measures Yang abruptly cuts them off.

“We need an even bigger sound from the violin, Alyssa!” says Yang, running his hand through his unruly black hair. Alyssa smiles and tightens her bow. “Try bowing closer to the bridge. And, Jennifer, the piano needs to land on that downbeat!”

Alyssa Rubinstein C’05, William “Rusty” Guinn W’04, and Jennifer Lee C’06 are studying the Brahms trio with Yang as part of their Music 11: Chamber Music seminar. Each is a highly trained instrumentalist who has chosen Penn over conservatory life. For them, Music 11 is a godsend: a chance to learn a rarely performed piece under the guidance of one of Philadelphia’s most exciting and gifted young coaches.

The students tackle the opening again. In one sense, the seven-minute finale has become as comfortable as an old shoe. They have long since mastered the notes, the dynamics, the intricacies of timing. But Yang’s intensive weekly coaching leads them to a continually deeper sense of nuance and ensemble. It is painstaking work, yet plainly everyone is having fun. This time, Alyssa’s violin blossoms, Jennifer’s piano asserts itself, and Rusty’s horn purrs. All the while, Yang stomps, points, and sings: Dee-ba-DEE-gee-tah-la! Bungee-dah DAH-dah! And he halts them again, right at measure 37.

The fourth time through, Yang peels off his sweater. It’s hot work, all this dancing and singing allegro con brio. By the seventh, eighth, ninth time —20 minutes into the one-hour rehearsal—the opening to the finale is transformed. Onto measure 38. Only 258 measures to go.

As the rehearsal progresses, the students listen closely—to Yang, to themselves, and most of all to one another. (“Above all, chamber music is a conversation,” says Yang. “To have a conversation, you must listen.”)

Suddenly Rusty has an idea. “What if we play this section at 277 a little tenuto? We could slow it down, to set the phrase off, and give it more importance.” Jennifer and Alyssa agree to give it a try.

“I like it,” Alyssa says, tentatively. She raises her violin, gives a nod with her scroll, and they practice Rusty’s idea again. Their coach steps back, smiling. It’s a priceless moment for Yang, the group working together, independently, evolving on its own.

“My value to Penn is as a performer who can coach, as opposed to a coach who can perform,” says Yang, a professional violist who plays regularly with major ensembles throughout the East Coast and has been directing Penn’s student chamber program since the fall of 2002.

Yang speaks with the urgency of a zealot. “Chamber music is democratic in the true sense of the word. You must learn when to blend into the fabric of background sound and when to play out; you must learn how to become part of the group without suppressing your own personality,” he says. “Chamber music is one of the most human activities that we can do. It makes us better people. I guess you could say that chamber music is my mission.”

As a teenager, Yang spent his free time stretched out in his bedroom, listening to recordings and studying quartet scores. Growing up in New York in the mid-1980s, he was one of a cadre of super-elite high-school musicians. He attended the pre-college program at Manhattan School of Music on weekends and played string quartets during the week with the likes of now-world-famous violin soloist Pamela Frank, a classmate of his at The Dalton School. Although he was qualified to audition for any of the top music conservatories, Yang instead decided to matriculate at Penn as an undergraduate architecture student in 1985, following in the footsteps of his parents, John Yang GAr’57 and Linda Gureasko Yang Ar’59. “My family always encouraged me to study what I loved, but it was also tacitly understood that I would pick something practical for a profession,” he says.

Two Penn degrees later, Yang was living in New York and pursuing a lucrative architecture career when he realized that something was absent in his life: chamber music. “I had actually stopped playing for several years while I was doing architecture, and I missed the viola,” he says. “There is a great physical joy in pulling the bow across the strings, and I found myself longing for that joy.”

In 1997 he left New York and architecture for a special chamber-music program at the San Francisco Conservatory and has never looked back. In this, he was once again following family tradition—both his parents have embarked on successful and passionate second careers: John Yang is now a prominent fine-arts landscape photographer and Linda Gureasko Yang is a former New York Times garden columnist who has written four gardening books.

Yang returned to Philadelphia three years later with his partner, Daniela Pierson C’92, a baroque specialist, and their infant daughter. He was quickly assimilated into the local chamber-music scene as both a player and artistic director, and within months he began to change the shape of chamber music in the city. In 2001, Yang founded a chamber-music series at St. Peter’s Church in Old City; by 2002 he had launched the Philadelphia Viola Society, the Main Line Chamber Music Seminar, and the children’s musical troupe Auricolae, as well as the Newburyport Summer Chamber Music Festival in Newburyport, Massachusetts. An ardent supporter of new music, Yang works continually to secure chamber-music commissions from emerging composers, including Penn’s Ann Kerzner Gr’02, Jeremy Gill Gr’00, and Noah Farber C’02. And he sees his coaching work as another natural extension of his life’s mission.

“I know what it takes to put together a really good chamber-music concert, which is why my groups work so very closely on details,” says Yang. “You spend time on technical aspects, yes, but as much time in just figuring out how to interpret a given measure, phrase, motive. And then zooming out and rediscovering the arc, the broad picture. You have to constantly go in and out, back and forth. This is what excites me—making music coherent on many different levels. An instrument in the hands of an accomplished player is capable of saying so much that we cannot say in spoken language, in English, French, or Chinese. That is why we play. To communicate specific thoughts—too specific for anything but the language of music.”

—Karen Rile C’80