Class of ’09 | Abdi Farah C’09 is everything you’d never expect from a reality-television contestant. Yet when we spoke with him in early May, he was sitting in his mom’s house in York, Pennsylvania, counting down the days until his small-screen debut.

“I think I’m a little too excited,” he was saying with a laugh. “Everything thus far has gone super fast, but this last month of waiting for the show to air is kind of excruciating.”

The premise behind Work of Art: The Next Great Artist, which made its Bravo debut June 9, should be vaguely familiar to those who have watched any of Bravo’s other reality-competition offerings (Project Runway, Top Chef, and the like). In this case, 14 aspiring visual artists, each specializing in a different medium, face a challenge every (television) week to create a masterpiece within the constraints they’re given. One by one, week by week, they’re whittled down until a winner is selected. According to Bravo, that lucky artist receives a solo show at the Brooklyn Museum as well as a cash prize of $100,000.

As the youngest contestant, Farah says competing and working alongside other artists, all at different stages in their careers, “definitely changed who I am as an artist.” The competition structure and challenges, he adds, “make you realize how many crutches you have and how many excuses you make on a daily basis, but it also makes you realize you can do some pretty cool, impressive things given some pretty strenuous confines.”

Though it lacked lights and cameras and boom mics, Farah’s childhood wasn’t so different from his time on the show; it featured lots of art supplies, and he maintained a razor-sharp focus on his craft.

“I can remember drawing before I can remember anything else,” he says of his toddler years. “I would always have markers or crayons or colored pencils; that’s what I did—I drew.” He wound up in a Baltimore art magnet middle school, followed by an art high school. While his experiences there reinforced his conviction that art could be a career, not just a hobby, “my world just got so small,” he says, “to a point where I was just this art fascist who didn’t see the point of doing anything other than art.”

Farah eventually realized that he “wanted to be around people who were doing other things, who were just as interested in writing or history or science as I was in art. I felt that was necessary for me to grow as an artist.” The solution was Penn, where he majored in fine arts and minored in religious studies. He took plenty of studio art classes, but other ones, too: psychology with Andrew Shatte; “The Devil’s Pact in Music, Literature and Film”; printmaking; art history.

“I had amazing art professors, but then I also had a lot of professors outside of art who got me thinking in different ways, which wound up helping my art more than art classes did,” he says. “That’s why I wanted to go to Penn—to be around these people who were just as weird about what they were focused on as I was about art.”

Over the years, he’s received numerous accolades for his work, including a 2005 Scholastic Art & Writing Portfolio Gold Award; a 2008 Yale Norfolk Summer School of Music and Art fellowship award; and several first-place awards from the Columbia Scholastic Press Association for his editorial cartoons in The Daily Pennsylvanian. Still, he insists that art isn’t about fame or trophies, or even reality-TV stardom.

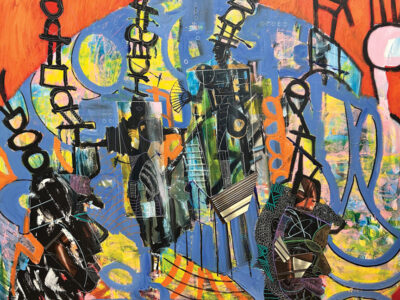

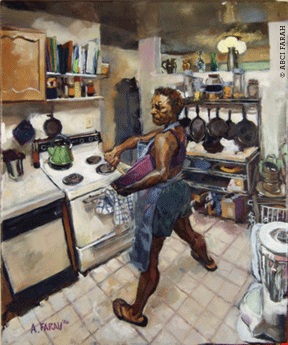

“I always hope to make art that brings people in and that they can enjoy and wrestle with and experience,” he says. “If I see a void in the visual world, I feel like it’s my role to fill it. I usually work in paintings or sculpture, but mediums don’t really matter to me. I love people and portraits and the human body, so my work is usually figure-based—it’s always spurred by an initial reaction to the physical beauty of people.”

The summer after he graduated from Penn, while working with the Philadelphia Mural Arts program and contemplating his next move, Farah came across an email from Joshua Mosley, the chair of Penn’s fine-arts department, about an open casting call for Work of Art.

“When I heard about it, I was just like, ‘This is it,’” he recalls. “I was freaking out, jumping up and down, telling my friends, ‘We have to do this, we have to get our portfolios together right now.’”

It turned out his friends didn’t quite share his enthusiasm, so Farah went to New York alone last July, portfolio in hand. He arrived early, certain he’d be one of the first ones there—then saw hundreds of people wrapped around three giant city blocks.

“My heart just sank,” he recalls. “I thought, ‘There’s no way they’re going to notice me in this sea of people.’ But I had nothing else to do, so I stayed in line for seven hours and they passed me on to the next round. It just snowballed from there.”

Farah hopes that after they see the show people will no longer consider the visual-art world “secret and mystical.”

“I think this show is going to help put the art world back into relevance,” he says. “If you ask a regular person, ‘Who’s a famous living artist right now?’ they’re going to struggle to tell you. If you ask them, ‘Who’s a relevant actor?’ they’re going to name 50. Visual artists have become fairly unknown people, which is sad.”

For now, he’s soaking up his last few weeks as one of those unknowns. He’s transformed his mom’s basement into a studio and her garage into a wood shop, and has been “making my art and trying to avoid the TV,” he says. “I’m going on with how my life would have been if I hadn’t gone on the show.” The one exception? He was hoping to get a TV before the show starts airing.

—Molly Petrilla C’06