A revival of W. E. B. Du Bois’s pioneering children’s magazine is sending out a “bat signal of resounding Black love.”

Karida L. Brown G’11 was combing through a W. E. B. Du Bois archive, deep into research for her upcoming book, when she unearthed a surprise: for nearly two years, the distinguished scholar had put out a magazine for kids.

Brown paged through letters that Du Bois had sent to potential contributors in the early 1920s. “He would tell them, ‘I’m asking for a piece of your best original work so that I can put it in The Brownies’ Book and Black children will know that they are thought about and loved,’” she says.

A hundred years later, Brown found herself and her husband, fine artist Charly Palmer, making the same request of prominent Black creatives and scholars. Brown had told Parker about her archival discovery back when they were newly dating, and the idea to resurrect The Brownies’ Book became a refrain between them. “We used to always say somebody needs to do this,” Brown says, “and over time that evolved to we need to do this.”

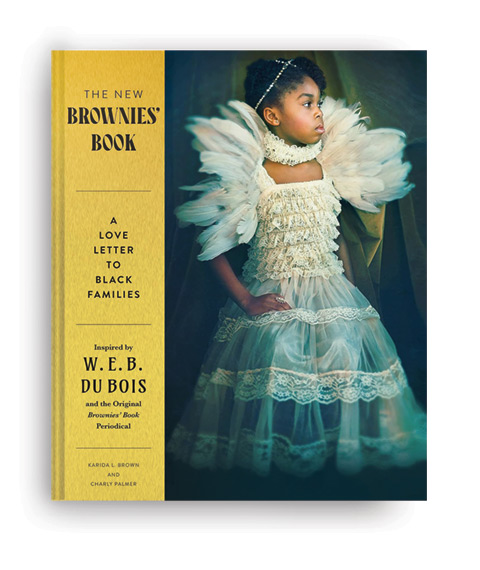

The New Brownies’ Book: A Love Letter to Black Families came out in October and by early November had already received a Publishers Weekly starred review, become an Amazon Editors’ Pick, and landed a slot on one of Oprah’s holiday gift lists.

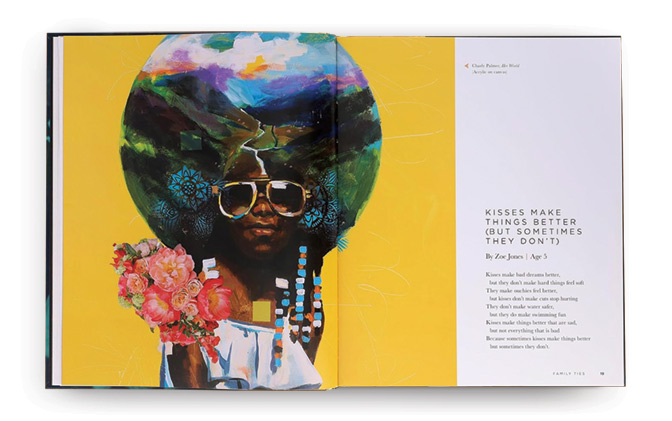

In a departure from Du Bois’s original magazine format, Brown and Parker’s Brownies’is a 208-page coffee-table book. It kicks off with a poem by five-year-old Zoe Jones. “Kisses make bad dreams better,” she begins, “but they don’t make hard things feel soft.”

From there, the anthology is filled with photos, plays, essays, comics, songs, games, poems, and paintings. Many pieces are warm and lighthearted, others more serious, and Brown contributed 21 mini-biographies of notable Black women, accompanied by illustrations from Palmer. Along with contemporary creatives, there’s a collection of writings from Langston Hughes—his first published works, all of which appeared in the original Brownies’ Book—including this short-but-sweet selection:

The little house is sugar

Its roof with snow is piled,

And from its tiny window,

Peeps a maple-sugar child.

“This was supposed to be like a bat signal of resounding Black love,” Brown says of the anthology. “Black people, including Black children, are still underrepresented or negatively represented via stereotypes in the mainstream media. We need as many positive and broad representations of the fullness and heterogeneity of Black people as possible. Du Bois knew that then and we know that now.”

Aside from requesting that contributors send an original work, “we gave them no rules,” says Palmer. The couple was shocked that almost everyone they asked agreed to participate—and surprised again by many of their submissions.

When Marcus Anthony Hunter—a sociology professor at UCLA who is credited with coining #BlackLivesMatter (about a year before the hashtag went viral in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s killer)—signed on as a contributor, Brown says she expected “some kind of history lesson for kids.” Instead, a free-verse poem titled “The Children of the Sun” hit her inbox, and “I was just on the floor” in shock, she says.

Another scholar sent in a playful story about a third grader discovering he’s lactose intolerant. (After the child’s sister suggests he has a tapeworm: “I also kept thinking…[i]f he was in there, could I talk him into coming out? Couldn’t he go find his own food instead of eating mine?!”)

Brown says she and Palmer enjoyed opening each submission and discovering these new sides to people they’d already admired. The couple embraced the genre-jumping spirit, with a poem from Brown and two pieces of prose by Palmer.

“I’ve never tried my hand at poetry before,” Brown admits, but diving into the unknown hasn’t stopped her before. In fact, it’s how she wound up at Penn and, ultimately, as a sociologist curating this book.

Brown majored in risk management and insurance at Temple University and was working as an underwriter on Wall Street during the global financial crisis in September 2008. “It was just an awful, confusing, jarring time,” she says, “and I didn’t want to be a part of it. I quit my career because of that.”

A friend suggested Penn, and she enrolled in the Master of Public Administration program at Fels, also taking Wharton and School of Arts & Sciences courses while at the University. “It was at Penn that I decided that I wanted to pursue a PhD, go into academia, and be the professor that I wish young Karida had had when I was in college,” she says.

After her “hyper-focused” undergraduate experience, “I knew that in pursuing a PhD, I wanted to find the broadest discipline possible,” she says. “With sociology, you can do anything. Nothing is outside the bounds of my field, which I think is beautiful and exciting. It keeps me interested every day in what I do.”

After receiving her doctorate from Brown University in 2016, she taught at UCLA and now Emory University. When the Obama Presidency Oral History Project launched at Columbia University in 2019, Brown joined its advisory board, helping to oversee the 400-interviewee endeavor, and even conducting the project’s first interview. In 2020, she became the Los Angeles Lakers’ inaugural director of racial equity and action, spending two years helping the NBA franchise develop a six-point racial equity action plan.

She’s published two books of scholarship so far: Gone Home: Race and Roots through Appalachia (2018) and The Sociology of W.E.B. Du Bois (2020). “I’ve been researching and writing on Du Bois’s scholarship for almost a decade now,” notes Brown, who was fascinated to learn about the sociologist’s brief teaching and research stint at Penn in 1896. “I just feel so connected to him, and I can’t explain how or why that happened. He is a part of me. His spirit lives with me.”

Discovering Du Bois’s original Brownies’ Book only deepened Brown’s interest and admiration. “I saw a different side of Du Bois,” she says. “I saw this commitment to children and how beautiful and sweet that was.” Necessary, too. Du Bois’s idea for a wide-ranging publication that would entertain and inspire young Black children “was so important then,” adds Brown, “and it’s still so important now.”

—Molly Petrilla C’06