“There is no Constitutional right to vote.”

So declared Seth Kreimer, the Kenneth W. Gemmill Professor of Law and self-designated “ghost of Christmas past” at a Penn Law forum on the state of ballot access and voter suppression in America today.

The 36th annual Edward V. Sparer Symposium, which commemorates the late professor of law and social policy, set its sights on an issue no less consequential than “The 2016 Presidential Election and the Future of American Democracy.” Its highlight was an examination of the impact of voter disenfranchisement on the most recent national and state elections.

It featured panelists drawn from the front lines of battles over voting rights and gerrymandering. Nina Perales, who has successfully argued two voting-rights cases before the US Supreme Court and is currently vice president of litigation for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, discussed her recent legal actions in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder, which invalidated a key part of the Voting Rights Act. Civil rights attorney Caitlin Swain detailed her own work supporting a suit brought by the NAACP against the State of North Carolina, which a federal court last July found culpable of issuing voting restrictions whose primary purpose was to disenfranchise minority voters via provisions that “target[ed] African Americans with almost surgical precision.” And journalist David Daley, author of Ratf**cked: The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy , delved into the unprecedented technology and sophistication of 21st-century gerrymandering.

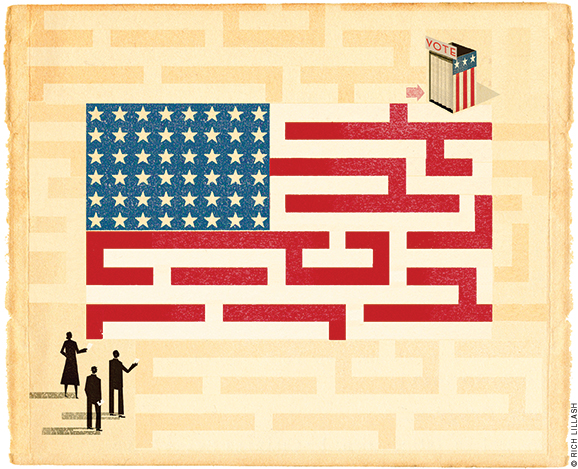

But first, Kreimer, an expert in constitutional and civil-rights law, illuminated an under-appreciated aspect of a country predisposed to see itself as a beacon of democracy: from the very beginning of our republic, mere citizenship has not guaranteed the right to vote—and the path to universal suffrage has been slow, tortuous, and full of reversals that continue to the present day.

“The Constitution,” Kreimer continued, “simply said that the right to vote in federal elections—and there were only elections for Congress at the time—was to be allocated on the basis of the same way that the states chose the most-numerous branch of their legislature.”

In all states, that meant the ballot box was the exclusive preserve of men. Most states further restricted the vote to property-owners, though these qualifications varied from place to place. (By some estimates, these restrictions disenfranchised half the white men in America.) And no state, of course, granted suffrage to people who were themselves owned by other Americans.

“That was the state of affairs for the first 80 years of the republic,” Kreimer said, before detailing its fitful evolution. Property-ownership qualifications were largely eliminated during Andrew Jackson’s presidency. The 14th Amendment, adopted in 1868, stipulated that states that barred male citizens above the age of 21 from voting, except on the grounds of “participation in rebellion, or other crime,” would face reductions in the size of their Congressional delegations. The 15th Amendment, adopted in 1870, mandated that the right of citizens to vote could not be denied on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

But that progress ran straight into a buzz saw of reaction and retrenchment. In 1875, the US Supreme Court ruled in Minor v. Happersett that the constitutionally protected privileges of citizenship did not include the right to vote—sought, in that case, by a Missouri woman who was denied on the basis of her sex. It would take another 45 years for the 19th Amendment to overrule that decision.

In the meantime, Kreimer said, many states set about reinstating the old racial impediments by alternative means.

“The 1901 Alabama State Constitutional Convention explicitly said: What we’re trying to do is minimize black political power, consistent with the 15th Amendment. We can’t take away their basic rights explicitly, but we have other ways to approach it. We can require literacy tests. We can require payment of a poll tax. We can require that there be ‘good character’ as determined by registry boards.” Combined with “grandfather clauses” that awarded the right to vote to citizens whose grandfathers had exercised it prior to Emancipation—providing poor and/or illiterate white men with an end-run around these restrictions—the results were unambiguous. According to historical records, Alabama and numerous other states stripped the right to vote from hundreds of thousands of African Americans, cutting the number of registered black voters by as much as 95 percent from their Reconstruction-era levels.

By the middle of the 20th century, Kreimer noted, “29 states had literacy tests—not just in the South. States increasingly had onerous registration requirements, taxpaying requirements. And the right to vote essentially rests with the states.” The Supreme Court agreed, upholding the poll tax in 1937 and literacy-test requirements in 1959.

“Only in the 1960s do things begin to change,” he continued, citing a case that finally established a principle that might be seen as a sine qua non of democracy, yet remained unrealized until the Reynolds v Sims decision in 1964: one person, one vote. “When Alabama has a disparity in voting power where in a rural county, every 6,731 voters can elect one representative, when in Mobile it takes 104,767 voters to elect one representative,” Kreimer summarized, “the Supreme Court holds that that sort of inequality violates the Equal Protection Clause” of the 14th Amendment.

A year later, the Voting Rights Act prohibited denial of the vote on the basis of race, and, importantly, required that jurisdictions with a history of doing so obtain “preclearance” from the US Department of Justice before making any changes to their voting regulations—“so that states can’t play whack-a-mole,” Kreimer said, imposing new discriminatory restrictions every time an existing one was ruled illegal.

That remained the main bulwark against voter suppression until the Supreme Court struck down the preclearance provisions in Shelby County (2013). “The Voting Rights Act still imposes limitations on actions that have the purpose or effect of limiting the right to vote based on race,” Kreimer said, “but now it’s up to plaintiffs to prove it. And once one limitation is struck down, the states can come back with another.” Which, since 2013, they have, “in a whole series of varieties. And now, rather than having the burden on states that exclude people from the vote to show that there are no racial intents or effects, the burden is on the plaintiffs to show that there is.”

That meant a substantial amount of new work for Nina Perales.

Shortly after the Shelby decision, she recounted, “the mayor of Pasadena, Texas, which is right outside of Houston, got a glorious idea to change the city’s election system. In the city of Pasadena, Latinos had been mobilizing in greater numbers. They had been registering and turning out, particularly in the most recent [municipal] election … and the mayor, who had been in office for many, many years, saw that his city council was now balanced evenly between Latino-selected candidates and Anglo-selected candidates. And that perhaps one more election cycle would see the council tip away from his control over the city.”

Latinos, she continued, felt that their side of town had been neglected in the distribution of municipal resources. They suffered pothole-ridden streets, on which many children had to walk to school for lack of sidewalks, and sewage-overflow flooding that presented a “stark contrast to the very beautiful conditions and maintenance by the city in primarily Anglo-Saxon parts of Pasadena.”

“The mayor advocated a plan to change the way city council was elected, in a way that was pretty obvious to everybody would make it impossible for Latinos to be able to elect a majority of council. It was a technique we’ve seen in many, many places where there’s a minority community: at-large elections. Instead of having eight neighborhood-based districts, the mayor suggested having six neighborhood districts and two at-large seats.”

When asked by SCOTUSblog why he was advocating this tactic, whose use dates to the Jim Crow era, Pasadena Mayor Johnny Isbell referred directly to the invalidation of preclearance in Shelby, responding: “Because the Justice Department can no longer tell us what to do.”

Electorally, the mayor prevailed—by a razor-thin margin of 87 votes cast on a ballot initiative.

“We argued to the court [that] not only were these changes dilutive in effect,” Perales said, “but that it was also intentional racial discrimination under the 14th and 15th amendments.

“Those of you have tried intent cases know it’s very difficult to persuade a federal judge to hold that there is intentional discrimination,” she told the audience, many of whom were lawyers attending to earn continuing-legal-education credits. “But we had a great coming-together of some wonderful evidence, amazing clients, some fantastic witnesses—and some exercise of poor judgment in what the defendants were saying in depositions.” A US District Judge ruled in the plaintiffs’ favor, and ordered Pasadena back in under the preclearance system.

Yet Perales deplored the costs of that victory, which stand to be multiplied by the number of other jurisdictions that pursue similar tactics. “The loss of Shelby County meant that we had to litigate this issue, which meant the city had to spend quite a bit of money, and the plaintiffs had to wait, and it also took a big chunk of our time and resources as well,” she said. “It cost millions of dollars—and we lost an election cycle, the 2015 election cycle, which was conducted under the discriminatory system.”

Caitlin Swain echoed that lament, drawing attention to the thorn on the rose of her clients’ much-heralded July legal victory in North Carolina—where, as late as October, registered voters were being purged from voter rolls by the hundreds through a state law that enables private citizens to challenge other voters’ eligibility ahead of elections. In this case, citizens issuing challenges—sometimes by the hundred—included local Republican officials who overwhelmingly targeted African-American and Democratic voters.

“North Carolinians have lived through at least three illegal election cycles,” Swain said. “That means elections that have been found by either federal courts or state courts to have been operating under either illegal redistricting schemes, or an illegal electoral process.”

Concerns about fraudulent voting, which frequently underlie laws restricting ballot access, are understandable but largely unsubstantiated, Perales added. Although stopping in-person voter fraud was the North Carolina legislature’s ostensible purpose, the court noted that the state “failed to identify even a single individual who has ever been charged with committing in-person voter fraud in North Carolina.”

Redistricting schemes were the focus of David Daley’s remarks, which sought to explain the GOP’s remarkable electoral turnaround after 2008, when the Democrats won the presidency and secured substantial majorities in the House and Senate.

While “despairing Republican strategists” worried that demographic changes spelled permanent trouble for the GOP, Daley said, “a handful of strategists based in the Republican State Leadership Committee” realized that 2010 would be a Census year, and therefore a redistricting year.

“What they realize is that there are fewer than 120 state legislative seats across the country that represent the difference between taking complete partisan control of the House of Representatives—that if they can capture these 120 specific state legislative seats, and tip control of those chambers, including right here in Pennsylvania, to their side, that they would have ability to draw more than 190 of 435 Congressional districts completely on their own.”

What followed, as Daley also detailed in Ratf**cked (a slang term for political sabotage often traced to Richard Nixon campaign operative Donald Segretti), was a $30 million dollar effort focusing on otherwise obscure local races in North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, and a few other states. It paid dividends. The state legislatures of Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Michigan, and Wisconsin flipped from Democratic to Republican control (which was retained in Ohio), setting the table for what may be the most consequential redrawing of legislative boundaries since the civil-rights era.

“In 2011, modern technology—the kinds of computer programs that are used now to draw these districts—have progressed to the point that each and every swiggle of these maps can have direct, specific intent,” Daley explained. “And the knowledge the mapmakers have of who we all are, on many levels—thanks to public records that can be added onto the mapping program, thanks to Census data, thanks to demographic data, thanks to social media and clouds’ worth of consumer preferences—they can all be uploaded into the kinds of programs that draw these lines … to such an extent that what we have seen throughout these last cycles are maps that are virtually impossible for the Democratic Party to win on, in many states—even when they have dramatically more votes.”

“You see this in 2012 at the Congressional level,” he continued, “but you also see it at the state level in North Carolina, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin. What you begin to see are veto-proof supermajorities for the Republican Party in states that are essentially 50-50, or even states where they often get fewer votes.” State election data underline this trend: in both North Carolina and Pennsylvania, for instance, more overall votes were cast in 2012 for Democratic candidates than Republican candidates, yet Republicans secured more than 70 percent of each state’s seats in the US House of Representatives.

“And what you see from the legislatures in these states after that is an explosion of legislation on voter ID, on voter suppression, on eliminating early voting, on changing the number of polling places that are allowed,” Daley said. This “explosion of intent and technology,” he concluded, has transformed “the gerrymander from sort of an age-old tool into something that has contributed deeply to the fact that we are a 50-50 country, but we are living at all levels [in 2016] under the control of one political party.”

Subsequent discussion touched on the latest battle in the long war over gerrymandering (which Daley quipped has been going on for as long as the US has been a republic, “and perhaps even earlier”). This is the Whitford v. Gill case, in which a federal district court ruled in November that Wisconsin’s state legislative districts had been unconstitutionally gerrymandered to favor Republicans.

“The Court over the years has said that they’re open to a standard that measures partisan symmetry—district plans that treat parties equally,” Daley said. “They have not been especially interested in questions of partisan intent,” he added, “but they’re open to the idea of being sure that votes translate into seats with equal efficiency—which is not the same thing as proportionality.”

The Whitford case provides a methodology dubbed the efficiency gap, which Daley described as “the difference between parties’ respective wasted votes in an election, divided by the number of votes cast.” Wasted votes come in two flavors: lost votes cast for candidates who are defeated, and surplus votes cast for winning candidates beyond the number they need to prevail. Gerrymandering essentially boils down to maximizing an opposing party’s wasted votes and minimizing them for one’s own party.

Consider the simplified example of a county comprising three districts, with a total voting population of 60,000 dyed-in-the-wool Whigs and 40,000 ultra-loyal Federalists. One might draw district boundaries such that Whigs outnumber Federalists by the exact same proportion in every district, in which case every vote cast for a Federalist would be wasted (as would many cast for Whigs). Alternatively, one might create two districts consisting almost entirely of Whigs and one populated overwhelmingly by Federalists: fewer wasted votes, and a higher likelihood that Federalists will get at least one representative. Or, one might create one district numbering 33,000 Whigs, and two where Federalists have a 20,000-to-13,500 edge, leading to the most wasted votes, and the most perverse representative outcome.

In Wisconsin, Daley continued, “political scientists who have worked on this [find] that from 1972 through 2010, the level of gerrymandering as measured by the efficiency gap remains essentially constant. It spikes in 2012 to the highest peak in the modern era, and it’s stayed there throughout 2012, 2014, and 2016. And it does, in effect, lean in one direction.” According to analyses by Nicholas Stephanopoulos and Eric McGhee, who pioneered the measure, in 2012 there were seven states with efficiency gaps representing more than two seats at the Congressional level, all of which favored Republicans. (Nevertheless, over the sweep of American history gerrymandering has been an equal-opportunity affair. The largest efficiency gap Stephanopoulos and McGhee found in an exhaustive 40-year survey was the result of “California’s infamous ‘Burton gerrymander,’” which favored Democrats in the 1980s.)

Whitford is headed to the US Supreme Court. “Essentially it’s aimed at eking out a 5-4 decision that would change the nature of partisan gerrymandering,” Daley noted. “And if you could create a standard like this, states would have to apply it when they are drawing their maps.”

If that came to pass, it would extend what Daley sees as the one bright spot for voting equity in general, and for Democrats in the most recent round of the gerrymandering wars. “In many ways, the only successes the Democrats have had have been through legal strategies that have challenged these maps. Their electoral strategies have not worked very well,” he said—which of course is the very outcome their opponents have tried to engineer by reshaping the districts in the first place. “But in Florida, and Virginia, where they’ve been able to mount legal challenges, they have gotten new districts and won seats.”

Yet that left it to the “ghost of Christmas past” to issue a cautionary word.

“I think it’s tremendously important to understand that over the scope of our history, it has not usually been the case that the struggle for justice has succeeded primarily in the courts,” said Kreimer. “And it’s never succeeded only in the courts.

“Talking to colleagues, organizing, and as President Obama says, grabbing a clipboard and running for office, are some things that you as lawyers can and should do—and if you want a just country, must do.”—TP