The shape of your nose, the color of your eyes, the age at which Rogaine becomes your best friend—these factors have long been attributed to your DNA. More recently scientists have revealed another trait that may be subject to genetic influence: violent and antisocial behavior.

It’s a nifty finding, but should it change the way court decisions are made?

That was the question at the inaugural event of the Scattergood Program for the Applied Ethics of Behavioral Health, a partnership between the Thomas Scattergood Foundation and Penn’s Center for Bioethics. Dr. Paul Applebaum, a professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law at Columbia University, explored the newly discovered link between male impulsivity and an enzyme called monoamine oxidase A (MAOA), whose prevalence in the body is genetically determined. As he demonstrated, transplanting this knowledge from the lab to the courtroom is a fraught task.

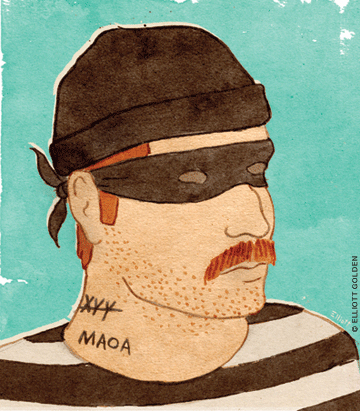

Discussion linking genetics to criminal behavior first blossomed in the 1970s, when studies focused on “XYY syndrome.” The thinking went that males born with an extra Y chromosome are more aggressive, since the Y chromosome triggers testosterone production.

Researchers predicted that increased aggressiveness and impulsivity in XYY men would make them more prone to criminal behavior. When initial studies showed that they were indeed overrepresented in prison populations, enterprising legal scholars were quick to pick up the issue.

“Right away, lawyers—particularly those with an orientation for the criminal defense bar—noticed that these data could have some implications for their work,” said Applebaum. Using the insanity defense as a precedent, lawyers argued that a defendant’s genetic endowment might impair his capacity to choose his behavior, and therefore excuse him from culpability for a criminal act.

Although later studies suggested that the original XYY research had been misinterpreted, current research has given more credence to a genetic link between male impulsivity and violent behavior.

Applebaum pointed to a study by University of Wisconsin psychologist Avshalom Caspi exploring the connection between the MAOA enzyme and antisocial behavior. Caspi and his colleagues showed that low MAOA levels correlate highly with increased impulsivity for males who have been abused or maltreated as children. For men with similar histories of abuse—but genes that produce high MAOA levels—the correlation was less pronounced.

“Interestingly, the courts were not terribly sympathetic” to appeals based on genetics, Applebaum said. “But the law’s skepticism doesn’t come out of the blue. Our Anglo-American legal tradition has generally viewed people as intentional actors [who] should be held responsible for their actions.”

Applebaum suggested that it might be more appropriate to use a genetic defense to mitigate sentencing, rather than to excuse criminal behavior. “If we’re not going to let people off the hook because of their genetic predispositions, you might ask whether we should take this sort of thing into account in sentencing,” he said. Since the decision not to commit a criminal act may be a tougher choice for those with low MAOA levels, perhaps they should not be punished as harshly as others, for whom the choice may be easier.

Yet that raises another thorny problem. “It’s making a rather odd argument, if you think about it,” he said. “In essence, the defense counsel is [saying]: Your honor, I ask you for mercy for my client on the grounds that he is much more likely than other defendants who come before you to do it again.”

“There’s some kind of conceptual non-alignment here that goes along with this argument, which suggests that it is more likely to be effective in theory than in fact before our very pragmatically oriented courts,” Applebaum said.

Whatever the legal implications of their work, researchers are going full speed ahead in investigating the link between genetics and criminal behavior. Their findings have already given birth to a handful of for-profit companies “that have announced plans to introduce a mail-order assessment for individual risk for antisocial behavior,” Applebaum said.

“So if you want to swab the inside of your kid’s cheek, pop that swab in a test tube, and send it back to the lab—they’ll tell you if he has a little Al Capone in him.”

—Leanne Ta C’09