The elusive creatures known as beaked whales

are facing unique threats to their survival.

By Richard Ellis | My guess is that you’ve never heard of beaked whales. That puts you in pretty good company. When I first proposed writing a book about them, practically every publisher turned me down by saying, “Who’s going to buy a book about whales that nobody’s ever heard of?”

Beaked whales are some of the most fascinating animals on earth. They don’t actually have a beak, of course, but because the skull has a long, pointed rostrum that reminded some people of the skull of a bird, this misleading name was applied. But in a most un-birdlike fashion, the skull of some beaked whales can be four feet long.

Beaked whales are some of the most fascinating animals on earth. They don’t actually have a beak, of course, but because the skull has a long, pointed rostrum that reminded some people of the skull of a bird, this misleading name was applied. But in a most un-birdlike fashion, the skull of some beaked whales can be four feet long.

The beaked whales, technically known as Ziphiidae, consist of 22 species of whales(not dolphins) that are among the least-known large animals in the world. The largest of them is Baird’s beaked whale, which reaches a length of 40 feet (this is the species with a four-foot long skull), while the smallest, the pygmy beaked whale, can be 13 feet long, still considerably longer than the familiar bottlenose dolphin. One of the reasons they are so unfamiliar is their modus vivendi: all beaked whales are deep-water dwellers (and the deepest divers in the world, but we’ll get to that later), rarely coming close to shore except to die—and we’ll get to that later too.

The typical beaked whale has a tapered, fusiform body; wide flukes that are not notched like those of most other cetaceans; and small flippers that lie flat along the body when the animal dives. There is a crescent-shaped blowhole with the horns pointing forward, and a small dorsal fin that is usually located much closer to the tail flukes than to the head. All members of the family have two throat grooves that converge toward the snout, and relatively small eyes, located back and away from the gape of the mouth. All beaked whales have a pair of grooves under the throat that converge toward the tip of the lower jaw.

The family Ziphiidae includes the genera Ziphius (one species); Berardius (two species); Tasmacetus (one species), Indopacetus (one species), Hyperoodon (two species), and Mesoplodon (15 species). Mesoplodon means “armed with a middle tooth,” referring to the two teeth in the middle of the lower jaw of the males. Many of the common names include the name of the person who first described the species, e.g., Longman’s, Sowerby’s, Blainville’s; while others—Hubbs’, Hector’s, True’s, Baird’s, Perrin’s—were so named by the original authors to honor a particular person. Some of the species are known by descriptive common names, such as “goosebeak whale,” “strap-toothed whale,” “ginkgo-toothed whale,” and “pygmy beaked whale.” Although nobody knows why, Mesoplodon grayi is known in New Zealand as the “scamperdown whale.”

The family Ziphiidae includes the genera Ziphius (one species); Berardius (two species); Tasmacetus (one species), Indopacetus (one species), Hyperoodon (two species), and Mesoplodon (15 species). Mesoplodon means “armed with a middle tooth,” referring to the two teeth in the middle of the lower jaw of the males. Many of the common names include the name of the person who first described the species, e.g., Longman’s, Sowerby’s, Blainville’s; while others—Hubbs’, Hector’s, True’s, Baird’s, Perrin’s—were so named by the original authors to honor a particular person. Some of the species are known by descriptive common names, such as “goosebeak whale,” “strap-toothed whale,” “ginkgo-toothed whale,” and “pygmy beaked whale.” Although nobody knows why, Mesoplodon grayi is known in New Zealand as the “scamperdown whale.”

At one point, the beaked whale Indopacetus pacificus was the least-known large animal in the world. Its existence was verified by two skulls: one found on a beach in Queensland, Australia in 1882, and the second in a Somali fertilizer factory in 1955. Random sightings and photographs revealed the existence of a bottlenose whale that was neither the northern nor the southern version; it was indeed a new species, the tropical bottlenose whale—and it was Indopacetus.

You may know that only the male narwhal sports that incredible ivory tusk, but you probably didn’t know that only male beaked whales have teeth, and most of these guys have only two, which they (like the narwhal) do not use in eating. (Like female beaked whales, female narwhals have no teeth at all.) We’re still wondering what Mr. Narwhal does with that spiral tooth, but we have a pretty good idea what the male beaked whales do with their teeth: they fight with them. Adult males are almost always heavily marked with scars that (probably) correspond to the paired teeth of rival males. Nobody has ever seen beaked whales fighting, but the females are unscarred, which seems to support the theory that the males scar one another.

Almost all adult beaked whales—male and female—are also adorned with oval-shaped, lemon-sized scars, which have been inflicted by small sharks known as “cookie-cutters.” The sharks’ common name comes from their feeding strategy of taking scoop-like bites out of large prey, such as dolphins, billfishes, tuna, and especially beaked whales. The cookie-cutter is a small, skinny shark, with teeth that differ in the upper and lower jaws; the uppers are small and thornlike for getting a grip, while the lowers form a continuous, sharp-edged band that removes the plug as the shark rotates on its long axis.

Whatever they’re used for, the teeth of male beaked whales are among the most unusual in the animal kingdom. Each of the 22 species can be identified by the shape and position of the two mandibular (lower jaw) teeth in the males, sometimes located at the tip of the lower jaw, sometimes in the middle. It is possible to imagine the species with teeth at the tip using them to scar their rivals, but those middle teeth might be a problem. The so-called saber-toothed whales have a pair of large teeth rising from the lower jawbone, which is often so strangely shaped that it must have been designed for no other purpose than to hold these weird teeth. (The jawbones of female saber-tooths are not so exaggerated, because they do not support any teeth at all.) One species has teeth shaped like the leaves of a ginkgo tree; another has a full mouthful of teeth like a dolphin; and in the strap-toothed whale ( Mesoplodon layardii), the male sprouts two teeth that grow upward and then close over the upper jaw, essentially locking the animal’s mouth shut.

The explanation for the male strap-tooth’s strange dentition is that all beaked whales (including the strap-tooth, the ginkgo-tooth, and Tasmacetus, the species with a full complement of teeth), are suction-feeders. They all have a pair of grooves under the throat that can be expanded when the hyoid bones inside the throat are pushed downward and the tongue pulled back, creating suction just the way you do when you slurp up something through a straw. When they echo-locate a food item in the depths—almost always squid—they approach it head-on, create the necessary vacuum, and slurp it up.

Like dolphins, beaked whales are echo-locators. They send out bursts of sound that bounce off objects in front of them, read the returning echoes to determine if the object is edible, and then gobble it up. Because they are breath-holding, oxygen-dependent mammals, whales can only remain submerged for a limited time before they have to return to the surface for a breath of fresh air—so they have to be able to capture enough food on each dive to justify the energy spent in diving so deeply. (Cuvier’s beaked whales now hold the record for deep-diving; radio tags have clocked them at depths of 11,000 feet.)

Squid breathe water through their gills, and spend their entire lives submerged, so they never have to surface, and can devote themselves to escaping from hungry whales. It is not immediately obvious how feeding whales can capture enough of the fast-swimming, darting squid to sustain their prodigious energy requirements, but the same question has plagued sperm-whale researchers ever since they discovered the loud sounds generated from the sperm whale’s gigantic nose. (Sperm whales are also suction-feeders, and feed primarily on squid, but not necessarily giants.)

Sperm whales can be found in almost all oceans, and narwhals only in the high arctic, but the various beaked whale species occur around the world in deep-water, offshore locations.

Until the 20th century, when scientists began searching for them at sea, almost all of our knowledge of beaked whales has been dependent on the finding of beached carcasses, or even skeletons, because they only venture into shallow water to die there. There are still a couple of species that have never been seen alive. It might be said that we know more about where beaked whales die than where they live. We are just now beginning to find out why some dead beaked whales are appearing on beaches around the world, and it’s not a pretty story.

The overall decline in large-whale populations, along with passionate objections to whaling per se, were the driving forces behind the passage of the International Whaling Commission’s 1983 moratorium on commercial whaling. The whaling nations that voted against the moratorium, and who wanted to continue the slaughter indefinitely, paid no attention to the beaked whales, because with the exception of Baird’s beaked whale and maybe the northern bottlenose, they were too small, too rare, too hard to find, and simply not worth the effort. Besides, we knew so little about their numbers (or even where some of them lived) that they came in, as it were, under the radar, free to live their deep-water, pelagic lives outside the threat of grenade harpoons. But in recent years, in our never-ending search for new and more efficient technologies, we have found new ways to threaten all kinds of whales, especially the beaked ones.

The Allies introduced sonar during World War II to track German U-boats in the Atlantic. Sonar locates submerged objects by sending sound waves through the water, and reading the range, bearing, and nature of the target by the returning echoes. Surface and submarine vessels use low-frequency active sonar (LFAS) as a navigational aid. Military ships use mid-frequency sonar (MFS) by firing bursts of sound through the water and listening for an echo off a ship’s hull. Blasted from subsurface loudspeakers, and aimed not unlike like a powerful searchlight on land, sonar powerfully—noisily—scans the surrounding depths. Some mid-frequency sonar can put out more than 235 decibels, as loud as the launch of a Saturn V rocket. Such blasts can affect the sensitive hearing apparatus of whales and dolphins in the vicinity, injuring them, causing them to beach themselves or otherwise behave strangely, and perhaps even killing them by cranial hemorrhaging.

On May 12, 1996, 12 Cuvier’s beaked whales stranded and died along the shore of Kyparissiakos Gulf in Greece. Necropsies revealed no evident abnormalities or wounds, but it was learned that LFAS “sound-detecting system trials” had been performed by the NATO research vessel Alliance the previous day. Volunteers managed to push five of the whales back into the ocean, but seven died. From March 15 to March 20, 2000, 15 beaked whales, a spotted dolphin, and two minke whales stranded or became trapped in the shallows of the Bahaman islands of Abaco, North Eleuthera, and Grand Bahama. During this period, US Navy warships were conducting sonar tests and maneuvers in the area.

Because they depend on sound to earn a living, the hearing of cetaceans has to be much more sensitive than that of all land mammals but bats. Injury occurs when there is a permanent threshold shift (PTS) that results in loss of hearing, likely to occur before non-hearing pressure injuries (barotraumas) caused by sound.

In a 2009 discussion of beaked whales and sonar, Taryn Kiekow, senior policy analyst for the Santa Monica-based Marine Mammal Protection Project, wrote: “Postmortem examinations of the beaked whales that stranded in the Bahamas revealed bleeding around their eyes, ears, and brains, which is consistent with acoustic trauma.”

Beaked whales are among the deepest-diving species, so sonar blasts might cause them to change their normal diving pattern and come to the surface faster, which would cause nitrogen bubbles to form in the tissues and lead to internal injury and possibly death. Indeed, when scientists necropsied 11 beaked whales that stranded four hours after mid-frequency sonar activity in the Canaries in 2002, they found that the animals “showed severe, diffuse vascular congestion and marked, disseminated microvascular haemorrhages associated with widespread fat emboli within vital organs. Intravascular bubbles were present in several organs, although definitive evidence of gas embolism in vivo is difficult to determine after death.” In other words, the sonar probably killed them.

For a thousand years, men killed whales for their oil, baleen, meat, and—often as a side industry—their ivory teeth. Although a few retrograde nations persist in the anachronistic business of commercial whale-killing, for the most part, whaling for profit has come to a merciful end. Yet large or small, beaked or beakless, by intention or by accident, people—military and civilian—are still killing whales. Now, just as we are beginning to unravel the mysteries of the living beaked whales, we find ourselves with an unprecedented number of dead ones.

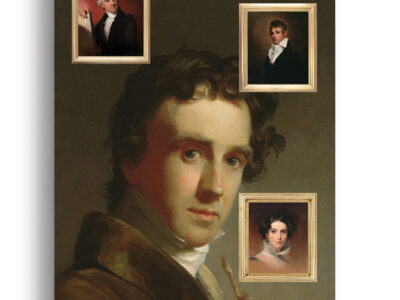

Richard Ellis C’59, a writer and painter, has written and illustrated 23 books about marine life, and is working on a book about beaked whales.