Four years ago, J.R. Lieber fell off the turnip truck in Texas. He hit his head hard.

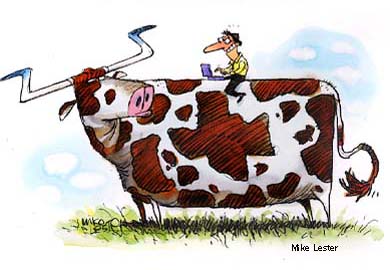

By Dave Lieber | Illustration by Mike Lester

LIKE THE AMERICAN pioneers of yore who headed west in search of freedom and fortune, this loyal Penn man (Class of 1979) and archetypal yuppie of the Eastern Establishment had hitched a ride on a covered wagon — in this case an American Airlines jet — to build a new life in a strange and exotic land. It was a place without the three necessities of life: cheesesteaks, bagels, or home delivery of The New York Times.

How could this penny-loafer-, buttondown-shirt-, and khaki-pants-wearing preppie reared in private schools and New England summer camps survive the harsh wilderness? How could somebody who grew up in the Yankee capital, New York City, someone who never saw a western movie, listened to a country music song, or watched a rodeo learn to say “Y’all?” How could he prevail in the land of the big-haired women?

Similar to the message painted by 19th-century pioneers on the front doors of their abandoned Midwestern homes as they headed for the Lone Star State, J.R. had GTT, short for gone to Texas. Yes, he had gone to the home of the hated Dallas Cowboys, chicken-fried steak, and l0-gallon hats.

This greenhorn had many strikes against him. He was a Jew moving to the buckle of the Baptist Bible Belt. A Bella Abzug liberal settling in a state that had elected and reelected Phil Gramm to the U.S. Senate. A divorcee in a place that supposedly cherished family values. Perhaps most troubling, though, he was the newly-hired columnist for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram — a member of the despised news media. And as Texas’s newest and least experienced newspaper columnist, he was supposed to offer Texans his opinions about how to act, think, and live their lives. In other words, he was supposed to act the way Texans thought Yankees were supposed to act — like a fathead know-it-all.

Not since those brave soldiers attempted to fortify a stone mission structure in San Antonio known as the Alamo had someone in Texas seemed so ripe for failure. By all expectations, the Yankee Cowboy should have been tarred and feathered, lynched from a Texas oak, or chased by a posse all the way back to his old haunt in West Philadelphia. How in the world could J.R. fit in?

And should he bother to try?

IF THIS SOUNDS like a Texas version of the television show Northern Exposure, that’s about right. I’m J.R. Lieber, but my classmates back on College Green knew me as Dave. However, after I arrived in Fort Worth, I decided I needed a nickname. Since the only Texan I knew — or thought I knew — was J.R. Ewing, I borrowed his moniker. Maybe somebody would confuse me with him.

Turns out the only one confused was me.

That first year in Texas was the worst of my life. Intimidated by every facet of Lone Star living — speech, dress, mannerisms, mores, and food — I struggled like General Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto. (He lost, thereby giving Texas its independence.) Without a doubt, I was Texas’s most-ignored newspaper columnist. In a cold blow, a local librarian commented that I wrote “like a Yankee.” Of course, she was correct. The little things threw me off. Was chicken-fried steak a chicken or a steak dish? Why was worshipping the Dallas Cowboys akin to membership in a cult? And how did all those women get their hair to stand straight up?

Living in the Quad had not prepared me for prairie life. The Penn Quakers? My old college team sounded wimpier than Texas Christian University’s Horned Toads. And what was a horned toad, anyway?

ON ONE OF MY FIRST story assignments, the newspaper sent me to Texas Stadium to cover a Garth Brooks concert. (This was long before Brooks packed them in at a concert in New York’s Central Park last summer; an idea, by the way, that I would have found laughable.) Naturally, my first question was, “Who is Garth Brooks?” At the time, he was practically the country music equivalent to Elvis. He sold out every stadium where he performed. And his fans wore the uniform — or costume — of the cowboy. In my penny loafers, buttondown shirt and tan khakis, I found myself lost in a sea of cowboy boots and black hats. When I tried to interview some teenaged girls about their affection for Garth, they looked at me and laughed uproariously. One actually said: “Get a load of this guy!”

During my first visit to Billy Bob’s Texas, the landmark cowboy bar in Fort Worth — which bills itself as the world’s largest honky-tonk — I was probably the only patron among the thousands who had placed a recent order with L.L. Bean.

Despite my efforts to cling to them, the old ties with home were fast disappearing. My beloved Phillies, then marching toward the 1993 World Series, had vanished from my world. Their games weren’t on local television, and the results in the newspaper were reported in minimal box scores. Every reference point, every beacon of familiarity was gone. I was like a head of cattle that got caught in the barbed wire. I was cut and bruised. But were my injuries beyond repair? My desperation apparently showed. One day I received a card from an anonymous reader that said simply, “Hang in there.”

EVER SINCE my heyday as a student columnist at The Daily Pennsylvanian in the 1970s, I had longed to work as a professional newspaper columnist. In my daydream, I lived in an old wood house by a small pond and peacefully wrote my award-winning columns by a window overlooking a rustic view. I was recognized at the supermarket, a popular after-dinner speaker, and a beloved and respected leader in the community.

Reality was quite different. One letter to the editor asked, “What right does Dave Lieber have to judge us?” Another chastised me as “ungodly.” The lowest moment, however, (aside from the Garth Brooks concert ) came during a speaking engagement at the Richland Hills, Texas, chapter of the American Association of Retired Persons. When one member asked, “Where exactly are you from?” I foolishly answered the question truthfully. Thus, this New Yorker came a little too close to becoming the first after-dinner speaker drawn and quartered by the AARP. Heck, a life sentence in prison could hardly have seemed worse to these seniors.

Penn man that I am — which means that despite evidence to the contrary, I’m no fool — I realized by my second year that there were some things that I couldn’t do, questions I could never ask if I wanted to thrive in this frontier environment:

1) Do you sell Nova lox here?

2) What’s the big deal about hunting?

3) Why don’t we enact some tough gun-control legislation?

And, I embarked on a multi-part plan of assimilation.

Bought cowboy boots.

Bought a cowboy hat.

Bought a belt with a big buckle.

Learned that chicken-fried steak was actually steak with a fried-chicken exterior.

Rode a bull in a rodeo (yes, really!).

Created the persona of J.R. Lieber.

One day it dawned on me that hating Yankees is the last acceptable form of bigotry in Texas. U.S. law prohibits discrimination based on race, creed, color, and now, sexual orientation. But nobody said anything about geographic bigotry. J.R. Lieber — the Yankee cowboy that everybody loves to hate, as he calls himself — founded a civil rights organization called yanks which stands for You Are Not Kind Southerners.

By learning to laugh, at myself — and indirectly at Texans — I managed to find myself. Plus, the more the locals learned about me, the more comfortable they felt with me. The turning point came on October 2, 1994, when newspaper readers opened their Sunday paper and read a column by me that began: “Here in Texas I’ve met the woman of my dreams. Unfortunately, she lives with the dog of my nightmares.” The story went on to describe my burgeoning romance with Karen, a local woman, and her two wonderful children. The problem came with Psycho Dog, Karen’s pooch, who detested me. It was a funny story about how the dog tried to drive me away from Karen, but in the end, the dog and I reconciled (somewhat) when I apologized on behalf of humanity to Psycho Dog for her previous owner, who had brutalized her. The story ended with me realizing that I couldn’t live without Karen, her two children, and the doggone little dog. The last line was, “Karen, will you marry me?”

Reaction was swift. The newspaper received so many calls at the switchboard asking about the outcome of my proposal that the publisher ordered a message put up on the electronic signboard over the highway. The sign flashed:

TIME 2:32

TEMPERATURE 59 DEGREES

KAREN SAID YES

DAVID LIEBER IS GETTING MARRIED

TIME 2:33

From then on, I had a new corps of readers suddenly curious about me, my new family, and my thoughts on their lives in Texas. I had the core audience I dreamed of, but what would I do about it?

THE NEWSPAPER columnist is, perhaps, a dying figure in our society. As television newscasts, the Internet, and talk-radio enjoy this era of dominance, as daily newspaper circulation continues to decline, the chances of another Jimmy Breslin exerting strong influence on a big city is fading. In the past year, iconic columnists such as Mike Royko, Herb Caen, and Murray Kempton have died. They will not be replaced.

I realize that I will never attain the status of my own columnist heroes, whom I read as a boy 30 years ago. But I also understand that I have an important opportunity to explain the inexplicable to my readers, even if they are different in outlook and background than me. Once they grew to know me and understand our differences, they began to watch my evolution from Penn man to Yankee Cowboy to fledgling Texan. All the jokes aside, I now understand that an outsider can bring a new perspective to a settled place filled with old-timers who sometimes need to be reminded of their own positives and negatives by someone with fresh eyes.

I’ve joined local historical associations, performed charity work, donated my time to area schools to help youngsters gain appreciation for reading and writing. I’ve fought dishonest politicians, honored local landmarks knocked down by developers, and tried to remind Texans that what they have is worth saving.

The many hours I spent in my old American Civilization classes at Penn, making mistakes — or “learning errors,” as I prefer to call them — at the DP, and practicing my craft at The Philadelphia Inquirer as a young reporter have paid off. You can go west, find a new life, and build a better one.

A few months ago, Karen and I gave birth to a son. We named him Austin because he’s something that his daddy can never be — a native Texan.

Yet all is not perfection. Psycho Dog still doesn’t trust me. The summers are a little too hot, even by the humid standards of Philadelphia. And I still can’t buy a pound of fresh Nova lox. But my victories come in small ways, usually in brief conversations with people I don’t know who stop me at the supermarket. (My daydream come true!) These readers tell me that they didn’t much care for me when I arrived. Some say they began reading my column, grew disgusted, and quit on me. But they confide that they eventually came back. These Texans gave this darn Yankee one more chance.

Maybe J.R. Lieber, the Yankee Cowboy, made them laugh. Maybe the story of Psycho Dog touched their heart. Possibly the birth of baby Austin won them over. For whatever reasons, I’ve found a new home — and happiness that I’ve never known before.

I have one wish, though. I’d like to find whoever sent me that “Hang in there” card and take them to a thank-you lunch.

The menu would be chicken-fried steak. With a bagel and lox on the side.

Dave Lieber, C’79, a metro columnist at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, was a student columnist for The Pennsylvania Gazette and The Daily Pennsylvanian. Two years ago, he was named top columnist in a contest sponsored by the National Society of Newspaper Columnists.