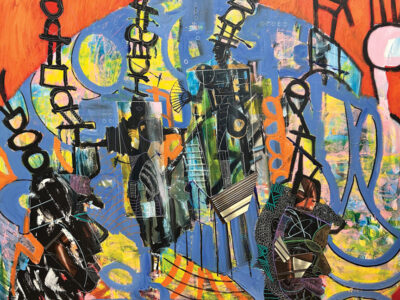

Curtis, by Jon Sarkin, 1994.

A literal stroke of fate transformed Jon Sarkin from a chiropractor and sometime-doodler into an artist who creates out of an obsessive fervor.

By Susan Lonkevich | Artwork by Jon Sarkin C’75

The nearly incoherent babbling of a drunk man filled the diner where Jon Sarkin, C’75, was eating breakfast one morning: “The free cheese is in the trap!”

To the rest of the customers, those rasping words must have sounded like gibberish, but to Sarkin, an artist for whom ideas often come flooding in unfiltered, they were a source of inspiration. “I loved that,” he says, “So I made a poster that says, ‘The free cheese is in the trap.’ What does that mean? The free cheese is in the mousetrap. Looking for the free cheese? Guess what. It’s in the mousetrap. It’s going to kill you! “

Sarkin

used to have a successful, if more conventional, career as a

chiropractor, often traveling around the country to give lectures. And

then his life took a “decidedly interesting turn.” A massive stroke

eight years ago, he believes, unleashed the unconventional artist

within. Since then, The New Yorker, GQ, and — according to recent reports — a Hollywood film production company, have taken notice.

“I’m free of the fetters of social convention that keep most people in tow,” Sarkin says, from his Gloucester, Mass. studio, explaining his changed world view. “Now I don’t give a hoot what people think. That is really very powerful for an artist.” Out of that sense of freedom, Sarkin creates colorful patchworks of cactuses and Cadillac tailfins and pointy-haired people, and a talking sculpture from a cab door. He arranges magazine clippings, photocopies, and drawings on posterboard collages. He takes quotations and inverts them so their new meanings are sharper or quirkier than the originals. At the beach, with no paper, he draws on rocks. “I don’t care. I just need to create.”

Sarkin originally wanted to be an artist, but decided an architecture

career sounded “more professional.” He changed his mind again during his

sophomore year at Penn and went pre-med. Medical school plans evolved

into dental school plans, which he later dropped.

Upon graduation, equipped with a biology degree from Penn but unsure of what he wanted to do professionally, Sarkin enrolled in graduate school at Rutgers University to study environmental science. Residents of the house he lived in at the time were interested in natural medicine; influenced by this, Sarkin decided to go to chiropractic school, and by 1982, he had established his own practice in Hamilton, Mass. “I was good at it,” Sarkin says now. “I worked hard, and I really loved what I was doing. I was successful financially, and I taught courses all around the country and was well respected in my field.”

Then came the ringing.

It

started with a golf game in October 1988. “I bent down to pick up the

golf ball, and I felt like this explosion had gone off in my head,”

Sarkin recalls. “I developed a ringing in my left eartinnitus

— and it was highly severe.” He suffered with this unrelenting,

unexplained condition for nearly a year while he sought the opinions of

specialist after specialist. Finally, a neurosurgeon traced the pain to a

swollen blood vessel pressing against the acoustic nerve in Sarkin’s

ear. He performed surgery in August 1989, which ended the tinnitus, but

caused a massive stroke and put Sarkin in a semi-comatose state for two

months.

After

a lengthy hospitalization and rehabilitation (a part of his cerebellum

had been removed), Sarkin returned to his chiropractic practice in 1990,

but sold it four years later. “I felt that my abilities were still okay

or else I would never have gone back to work and subjected my patients

to that, but I felt like it was time to try something else,” he says.

Sarkin won’t discuss how he now supports himself and his family.

Although

he had little formal training, Sarkin had always been artistically

inclined, with a slightly off-beat flair for the visual. “Even when I

was a chiropractor, if I had a party, I would design the invitations,”

he says. “On the phone I would do doodles that were nicer than your

average doodles, and would save them. And I always put more thought into

where things would go in my house, visually, than it seems other people

did.”

That artistic bent mushroomed after his stroke.

“Thoughts of projects and ideas just flood into me,” Sarkin explains. “Let’s say you have an idea. Most people have a barrier to an idea. There’s a filter. Know what I’m saying? Understand? That filter’s been removed for me. I see things. Let’s say you see a pattern in a cloud that looks like a whale. You’re like, ‘Well, that’s really nice and all, but I’ve got to go back to work because I have a deadline.’ If I’m walking down the street, and I see a cloud that looks like a whale, I go back to my studio and make a drawing of the cloud that looks like a whale, I make a sculpture of the cloud that looks like a whale. I get my camera and take a picture of the cloud, and I blow it up…So the things that everybody sort of just casts aside have taken on a significance for me that’s obsessive.”

It was actually Sarkin’s younger sister, Jane, who “discovered” him

several years ago. “She said, ‘Do you still do those doodles you used to

do [while talking] on the phone? Well, I think your doodles are really

good. You should send them in to TheNew Yorker

magazine,'” Sarkin recalls. “I said, ‘Hey, what the hell. It’s like a

lark. I’ll send them in and get a rejection.’ Two weeks later they call

me up and say, ‘We like your drawings and we want to buy some.'” Since

then, Sarkin’s works have been exhibited in New York, Gloucester, and

Rockport, Mass., and he was profiled in the January 1997 issue of GQ magazine, which also reprinted

several of his works. More recently, it’s been reported that Tom Cruise’s film production company has agreed to purchase the movie rights to his life story. (Sarkin says his attorney has advised him not to comment.)

Along

with Sarkin’s emerging artistic gifts have come physical disabilities.

He walks with a cane, sees double, is deaf in one ear, and must speak

slowly and deliberately to avoid slurring his words.

The

double vision actually is an asset for an artist, Sarkin says. “If you

ever look at something, and it sort of looks like another thing, that

phenomenon for me has been increased.” Many of Sarkin’s works, in fact,

look like they were created by someone with a fly’s multiple, fragmented

vision.

But

the after-effects of the stroke that Sarkin believes have enriched his

art have strained his family life. “It has changed my relationship with

my wife and my children tremendously,” he says. “Usually you can go to

the beach, you can run after your kids, carry your kids on your

shoulder, go skiing with your kids, carry your kids up the stairs…”

Sarkin can’t. He says his three children, ages two, five and nine, only

partly understand his condition – “in the ways that kids do.”

Almost

daily, Sarkin does something that frustrates his wife, Kim, because

it’s so irrational. He says, “She’s like, ‘Jon, what am I going to do

with you?’ I’m like, ‘Kim, what am I going to do with me?'” Even

around strangers and acquaintances, Sarkin’s lack of an internal censor

often gets him into trouble. “I say things without really thinking

about the consequences of what I say.” He also often takes things that

others say literally that were intended otherwise. One time, for

instance, a relative who wondered if he had enough money for a cab ride,

asked him, “How’s your financial situation?” Well, Sarkin said, he had

recently met with his financial advisor…

Sarkin

speaks slowly because of his disability, but when he explains his art,

ideas come tumbling out of him. “I get these motifstail fins or cactuses or the Chrysler Building or King Kongand

I just work them to death,” he says. “For some reason, I like Superman,

and I just go crazy doing pictures of Superman. I like the blues, and a

lot of my pieces revolve around the blues. The movie Taxi Driver,

for some reason, just hits me… I made a sculpture that’s a cab door,

and in the cab door there’s a tape recording loop. I recorded the part

of the movie that says, ‘Are you talking to me?’ There’s an actual cab

door that says, ‘Are you talking to me? Are you talking to me? Are you

talking to me?’… I’m into fish. I’ve probably made 20 different

drawings of fish. Cactuses, I’ve probably made 50. Cadillac fins, I’ve

probably made 20.”

Why tail fins? Why cactuses? Why fish? “I like the way they look,” says Sarkin. Why Taxi Driver? “I like the way it sounds. I like the way it feels. I like the way [tail fins] make me feel. I like the associations with when I was a kid and my parents had a car like that. I just like the whole American ‘can do’ thing of the fifties, which is epitomized by the Cadillac.”

Sarkin says, “I’m very aesthetically drawn to certain things. Often, I’ll thumb through a magazine and say, ‘I like this, I like this, I don’t like that.’ The things I like I tear out and put up on the wall of my studio, and I’ll get my inspiration.”

At any given time, Sarkin may have 50 different works in progress. “My latest project is this: I’m working on this poster with all these colors. I use words a lot in my art. This one says, ‘Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom,’ That’s Kierkegaard. I was at a friend of mine’s house and saw that on the wall, and I thought, ‘Is that cool?’ I also like flipping things around to see how they would sound. Lately I’ve been thinking about, ‘Dizziness is the anxiety of freedom.’ You like that? How about, ‘Freedom is the dizziness of anxiety’?” In Sarkin’s studio, the famous quote from Love Story gets a slightly cynical twist: “I made this thing that says, ‘Being sorry means never having to say you’re in love,'” he says, delighted. Even Shakespeare gets rewritten: “To be or to be. That is the no-brainer.” Lesser-known bards and philosophers, such as the drunk man in the diner, have inspired Sarkin, as well.

Dr.

Martha Farah, a Penn psychology professor who specializes in cognitive

neuroscience, says it is possible that Sarkin’s artistic abilities could

have been enhanced by his stroke. Although she’s not familiar with his

specific circumstances, she says, Sarkin’s comments about losing his

internal censor and interpreting things people say in a very concrete

way “are very common occurrences after frontal lobe damage.” But what

she finds most intriguing is a description of the recurring motifs in

Sarkins’s art. To her they sound like an unusual example of

perseveration. Perseveration has been observed in patients with frontal

lobe damage performing simple motor tasks, Farah says. “Like if they’re

pushing some buttons on a machine and then they need to turn a dial,

these patients will often continue pushing … They kind of can’t stop

themselves from carrying on with what they started. We also see it in

more abstract situations like conversations. Whatever topic the

conversation begins with, they’ll tend to keep coming back to it and

won’t let it drop. Perseveration cuts across all different realms of

behavior, but I’ve never heard of anyone who was an artist experiencing

perseveration of a subject or theme for their art…In general, most of

the effects of frontal lobe damage really are disabling for people in

their work life and in their social relationships,” Farah says. “It

sounds like this man either has truly found this perseveration is

helping him as an artist or is doing a good job of trying to look at

things in a positive light and find some artistic benefit in what must

be a difficult change in life.”

Sarkin saw the movie Shine

recently and felt in some ways he was watching his own story, “the

story of a guy who has artistic yearnings, however, he undergoes some

transformative event [that] changes everything about the way he relates

to his art. It’s very intriguing to me how you bring something to the

table, and then the table is altered dramatically, and then the thing

you bring to the table is altered dramatically, as well.” The aftermath

of his stroke would be unbearable, and his art would be impossible, he

says, were it not for family support, especially from his wife, who has

stuck by him through every exasperating incident, who “handles our

finances and all the driving and all the stuff it takes to deal with a

family.” Sarkin says, “Because my feet are grounded in the earth by my

wife, I’m allowed to have my head in the clouds.”

Despite

his artistic success since his trauma, Sarkin says, “I would give

anything in the world not to have had a head stroke. But I did. And as

my Mom says, ‘When your life gives you a lemon, you make lemonade.’ You

have to use that. Promise?'”

Sarkin’s website.