When Jonathan “Jack” Warner began collecting 19th-century American art, many people thought it was a frivolous investment at best. It was nice enough, they said—and certainly cheaper than the European works other collectors were fighting over—but frankly, why bother?

“This was the 1950s, and no one was collecting [early] American Art at the time,” says Lynn Marsden-Atlass, curator of the University’s art collection and director of the Arthur Ross Gallery. “It was deeply out of fashion.”

Over the last 60 years, Warner has taught those doubters a valuable lesson in foresight. The 2,000-plus pieces of fine art he amassed for his personal, corporate, and foundation collections are now some of the most sought-after and valuable works in American art, appraising for millions and even tens of millions of dollars. They’ve also become important pieces of the country’s historical record: “Through his collections, [Warner] is telling the story of America,” Marsden-Atlass says. “He’s a proud American, and the art he has collected truly documents the evolution of his country.”

A sampling of 60-plus works from Warner’s deep collections recently hit the road for the first time, heading first to the New Britain Museum of American Art in Connecticut and now to the Arthur Ross Gallery. Titled An American Odyssey: The Warner Collection of American Art, the exhibition features oil paintings, watercolors, charcoal drawings, and other works from more than 30 American artists. The all-star lineup includes Thomas Cole, Albert Bierstadt, Winslow Homer, Thomas Moran, Childe Hassam, Frederic Church, and members of the Wyeth and Peale families.

The works on view were created over the course of 150 years, starting in the early 1820s. The earliest piece in American Odyssey, a two-inch miniature portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart, provides an appropriate jumping-off point for the rest of the exhibition, which Marsden-Atlass describes as “the documentation and evolution of America.” Still-lifes abound, while other works offer glimpses of American life and popular activities from over the years: swimming, boating, farming, child-rearing—even a large colonial wedding and a 19th-century “sewing party.”

Other paintings illustrate the changing scenery around the country: up north in the Catskills and the New Hampshire mountains; down south near the Kentucky River; out west in Wyoming and Colorado. Among those landscapes are a trio of oil paintings from Thomas Cole, the artist who pioneered the first major landscape-painting movement in America and founded the Hudson River School—a mid-19th-century art movement that extolled the American outdoors. Hunters in a Landscape (1824-25) and Autumn Landscape (1827-28) represent two of his earliest works, while a later painting titled Catskill Mountain House (1845-47) highlights an area that he and his Hudson School contemporaries often visited.

Picking Flowers (c.1881) by Winslow Homer.

Washington at Valley Forge (1946) by Andrew Wyeth.

“Cole and the other Hudson River artists painted all the splendor and majesty and unspoiled, untouched nature they saw in America,” Marsden-Atlass says. “And truly, [those qualities] were one of the country’s greatest powers.”

Moving forward in time and sideways in place, four watercolors from Winslow Homer reveal the beauty and strength of the sea and, in Picking Flowers (circa 1881), the simple pleasures of American life. Nearby, three works from iconic American artist Childe Hassam showcase the impressionist style that he helped transport from France to America. (Hassam also helped found a group of American artists known as The Ten—a club that Homer refused to join.)

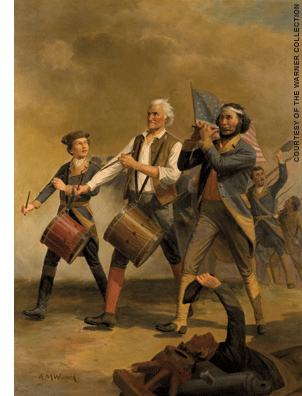

Even in the more recent works, Warner has selected artists who are paying homage to the country’s roots. Andrew Wyeth peers into the past with Washington at Valley Forge (1946), a drybrush watercolor in which he imagines what that moment in history might have looked like. Another 20th-century artist, A.M. Willard, also envisions the country’s founding fathers in his most famous work, Spirit of ’76 (1912). In the painting, three military field musicians—two drummers and one bandaged fife player—march in celebration of their victory in the Revolution.

While all the works on view are important individually, Marsden-Atlass notes that the collection reveals as much about one man’s dedication and eye for art as it does about the pieces themselves.

“These were all selected by Jack Warner,” she says. “It’s his eye, and he has an exceptional eye. The paintings in and of themselves are exceptional, but it’s equally remarkable that [Warner] purchased them so early. I think the depth and breadth of the collection he built is very unusual.”

The source of his prescience is simple, he says now: “I wanted them.” On the phone from his home in Alabama, Warner—who just turned 94—speaks frankly about the artworks in his collection. “I thought they would become important and that people would consider them beautiful,” he says, “but I didn’t have any idea that they would become as valuable as they have.”

Warner says that his collection grew out of an early fascination with wildlife artist John James Audubon. He bought a few Audubon prints first, then slowly amassed the artist’s entire elephant folio (the term for a large-format book) of birds. Before long, Warner found himself in an auction house bidding on Charles Bird King’s paintings—more specifically, his Native American portraits—and after that, rounding up works from the Hudson River School artists and others. Better yet, he says now, he was picking them up for practically a song. “Official art put their thumbs down on [those works],” Warner says. “You could buy them for prices to paper up the walls or keep the rain out.”

Over the course of the exhibition, Marsden-Atlass says she plans to collaborate with Penn’s fine-arts, art-history, literature, and history classes. “American Odyssey offers us a fabulous opportunity for interdisciplinary learning,” she says, “and I’m hoping that professors from across Penn decide to use it as a learning tool.” (To that end, the Ross Gallery will host the third-annual Jack Warner Symposium on American Art on October 21.)

For the students, academics, and anyone else who visits his collection at Penn in the coming months, Warner has a modest wish: “I hope it makes a better American of them.”

—Molly Petrilla C’06