Two 19th-century brothers, raised on their family’s slave-worked plantation, left Penn for very different destinies.

By Joseph N. DiStefano

My niece, who’s applying to Penn, recently asked my son, a College junior, to help put together a list of any family members who had attended the University. It’s one of the questions on the application.

Our list goes back. It includes the brothers John and Philip Hartmann, whose parents, US citizens and coffee plantation owners in Baracoa, Cuba, sent them to Penn before the Civil War, when the University was still located at 9th and Chestnut streets in Center City. Philip is my ancestor, five generations gone.

The brothers left Penn for very different careers.

John Jacob Hartmann C1828 G1831 (who sometimes Hispanicized his name to Juan Santiago) took his degree and headed home to Cuba to help his father manage their slave-worked farms. Baracoa, on a bay Columbus praised for its beauty, was an isolated port, once favored by seagoing pirates and then by foreign planters like John’s parents, who used enslaved Africans to work their fields of luxury export crops: coffee, cocoa, and sugar. One of John’s uncles had been mayor of Philadelphia, and the family maintained its useful connections. In 1843 Secretary of State Daniel Webster named John the town’s US consul.

After his father’s death in 1850, John and the family left Baracoa. The port’s trade had fallen with the price of coffee. Killer cholera spread that summer. Baracoa’s historian, Alejandro Hartmann Matos—a distant cousin via Haiti (it’s complicated)—tells me the family slaves abruptly disappear from church records at this juncture. Whether they were sold, seized for debts, or freed, as one branch of the family maintains, we don’t know. Hartmann Matos suspects they were sold.

John, now head of the family, moved to Philadelphia with his mother, sisters, and brother-in-law. He went into the cigar and Cuban imports business, and lived as bachelor-patriarch of the clan in a big house on Vine Street. He served on the city Board of Trade and Board of Education, and as an officer of the Union League club, which backed the victorious North in the Civil War. He died in 1892 and left $140,000, mostly to his sister’s sons.

If his father had chosen Penn to prepare John for the transition from two-fisted colonial slavemaster to civic-minded Republican merchant, the son’s career made the tuition look like money well spent.

But how, then, can we explain his kid brother’s very different career?

Philip Charles (Felipe Carlos) Hartmann M1849 studied at Penn’s Medical School under pioneering anatomist and public-health advocate Dr. William Horner. Philip wrote a treatise titled “Gun Shot Wounds,” returned to Cuba after graduation—and went native. Instead of joining his brother and the rest of the clan back in Philadelphia, he married a descendant of another Hispanicized Philadelphia family—Isabel Carman, of Buenos Aires—then built his practice and raised their large family, first in the plantation country around Guantánamo to Baracoa’s south, and later in Santiago, 700 miles east of Havana.

Philip’s practice went beyond the planters. As head of the local medical society, he treated patients of all classes, even curing wounded rebels in defiance of the Spanish military government. He campaigned for clean city water, against the temporal power of the Church, and pressured French humanist Victor Hugo and ex-President Ulysses S. Grant to back the cause of Cuban independence. According to his friend, the rum distiller and Santiago mayor Emilio Bacardí Moreau, Hartmann laughed at French-descended Guantánamo planters who lamented being “ruined” by the loss of their runaway slaves in the long independence fight: “You sang them the ‘Marseillaise’ and the ‘Ça Ira.’ They’re doing as you did!”

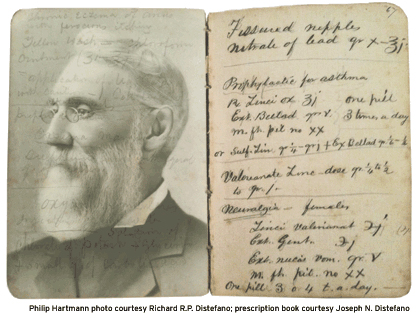

Philip declined to be a Philadelphia gentleman, but he didn’t abandon the city entirely. He sent sons and daughters to schools there, and his hand-written prescriptions book from the 1880s—in colored inks and leads mixing English, French, and Spanish—listed over 200 remedies for conditions ranging from fevers and tumors, to sexual and children’s ailments. He used quinine and yuca, opium and hemp, phosphorus and silver nitrate, and the whole homeopathic trans-Atlantic herb garden. His notes cite Philadelphia pharmacists and articles in Philadelphia medical journals. My grandfather said Philip took them home to Santiago, to read by candlelight.

Philip is supposed to have been an innovative surgeon. An article on Cuba’s EcuRed (Cuba’s state-run online encyclopedia) by two Guantánamo historians says he was the first on the island to operate on ovarian cysts. An article he published in a California medical journal, in 1888, is an efficient, damning indictment of the colonial authorities in the previous year’s Santiago smallpox epidemic. He documents the city’s lack of sanitary drainage, neglect by the Spanish government of the black majority population, the governor’s failure to vaccinate the poor and isolate the first smallpox case—or any others, despite Philip’s urging—and the apparent spread of the disease via wastewater drained from a hospital into “an alley inhabited mostly by colored people.” The fatal result: “In the month of June, two hundred and six died; July, three hundred and sixty-four… In the portion of the city inhabited by the wealthier and better-educated classes, there was not a single case.”

His granddaughter and assistant Katie Woodcock Hartmann was a blond 17-year-old when the US Navy bombed Santiago during the Spanish-American War of 1898. An eyewitness account by the journalist Joaquín Navarro y Riera shows her amid the refugee evacuation leading the white-bearded Philip in a horse cart to the guerrilla lines toward her fiancé, a captain in the Liberation Army of rebel General Calixto García.

When Philip died the next year, after the victory of the rebellion, he was honored with a public procession and buried near the grave of fellow Cuban patriot José Martí. One of the central avenues in Santiago was renamed Calle Hartmann. His tomb and his modest office remain points of medical pilgrimage. Bacardí wrote a long eulogy praising him as a democratic doctor who showed “the same diligence [for] the slave in his physical and moral suffering as the master,” and as a man “idolized by the oppressed.”

Philip’s effusive death report from the General Alumni Society (now Penn Alumni) says Hartmann’s “charity knew no bounds, and that he was called ‘el Medico de los Pobres’”—the Doctor of the Poor. “The question of money never crossed his mind, and even the rich had difficulty in obtaining a bill from him. He died poor, but his death was very much regretted.”

What did the Hartmanns learn at Penn? John was a member of the Philomathean Society, which in those days focused on the Greek and Latin classics, ancient examples of men forming and executing moral and practical ideas and using them to manage people and property. To us these old ideas of liberty and community seem incompatible with slavery; indeed the Whig party John supported split beyond repair, around the time he left Cuba, on this issue.

There’s no evidence John ever admitted a contradiction. There were plenty of Southern slaveholder sons who came home from Northern colleges with new arguments for justifying injustice. If he chose Philadelphia, trade, and civic service, over trying to expand his father’s slave-based fortune in Cuba, that was a trend of the times, and perhaps the easier course. He left his heirs comfortable.

I’d like to see the origins of Philip’s philanthropy in his mentor William Horner’s humane and scientific values, and to believe that Penn Medicine gave him the moral tools to realize that his schooling and his station in life had been made possible by the forced labor of others, a debt he might address by serving others.

Yet Philip’s public generosity came to some extent at his children’s expense. Bacardí quoted him on the meaning of human suffering: “Only with pain do we grow and strengthen; it is not possible to build without destroying. It’s the great work of humanity … To die is to evolve.” How does one apply such sacrificial values at home? My mother recounted a story of how Philip once whipped a grandson publicly, without stopping to dismount from his horse, when he found the boy gambling in the street during school hours. It’s easy to imagine the effect of his ferocious idealism and demanding standards on youngsters who may have had their own, different goals.

Eight of Philip’s children reached adulthood, but three of his adult sons died before him, at least two of them in tragic circumstances after frustrations in love or career. The fourth left Cuba for the United States. Three of Philip’s daughters applied to the Cuban Senate after his death, begging a pension, citing their poverty and noting he had given his resources to Cuba, leaving them poor.

From similar backgrounds the Hartmann brothers made very different choices in their lives. I pray my children find among their professors and fellow scholars people whose ideas and examples will help them, not only in their careers, but in the moral choices they will make in life, and in their ability to bear the consequences.

Joseph N. DiStefano C’85 writes a daily business column for The Philadelphia Inquirer, and the PhillyDeals blog for philly.com.