One hundred years ago this week, the School of Social Policy & Practice (SP2) was born. Kicking off a two-year celebration of that centennial in September, Dean Richard Gelles booked a keynote speaker not generally known for a congratulatory style.

“It would be a mistake,” Gelles explained to several hundred students and faculty assembled in the Annenberg Center’s Zellerbach Theatre, “to simply bring in a person who would make you all feel good.”

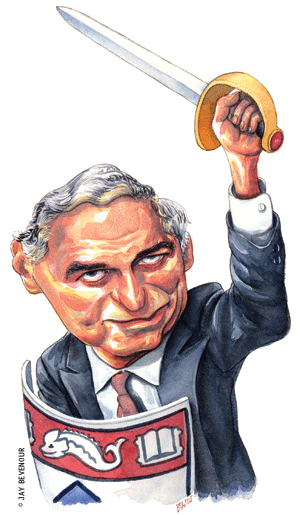

By that measure, longtime citizen advocate and five-time presidential candidate Ralph Nader was a perfect fit. Addressing a student body that contributes more than 250,000 hours’ worth of social and human services to the greater Philadelphia area every year, Nader issued a striking challenge.

“We must discipline ourselves so we don’t feel all that good when we engage in charity,” he declared. “At universities, lots of students spend time volunteering for charity. Not many spend time advocating for justice.”

Students in SP2, which became part of the University in 1948 and has gone through a few name changes, do something that neither word quite describes. “It’s not charitable giving,” Gelles put it afterwards. “It’s sweat equity. They are doing the work of social workers.”

That ranges from case management of children in foster care, to social services in the transplant and oncology units at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, to involvement in programs for immigrants and the elderly.

So in one sense, Nader was preaching to the choir. “Our students’ contribution to social justice is not to write a check. They’ve made a commitment,” Gelles said.

“But what is important for them to see is the other ways people pursue social justice and social issues. Nader was a lawyer, he wasn’t a social worker. He pursued it through the legal arena. He pursued it when it wasn’t popular. He pursued it at personal risk. He continues to pursue it even when people say that his pursuit will damage his ability to accomplish anything. And I think that’s an important message to hear.”

Not everyone was keen on Gelles’ invitation. “Some of our graduates, and some of our board members, and some of our faculty made it known to me immediately that it did not sit well with them,” the dean said while introducing Nader.

“That was my intent,” he added. “Because as I look at the school’s mission statement—and what our students do and what our faculty do—we are in the social-justice business. And being in the social-justice business is not always popular. It’s rare that everyone agrees with everything we do. And in my lifetime, the person who I have seen move the needle more consistently turns out to be a person who in the last eight years has become quite controversial.”

Much of that controversy, of course, stems from Nader’s run at the Oval Office in 2000, which many Democrats believe cost Al Gore the election. One could also contend that Gore’s own campaign was what cost him the presidency, and that these contests are meant to be competitive affairs. Whatever the case, Gelles found that Nader’s recent presidential campaigns have overshadowed what many would consider a more important legacy.

“I had people come up to me and say, I didn’t know he was responsible for seat belts. I didn’t know he was responsible for the Freedom of Information Act,” Gelles remarked. “For a reasonable population of my students, and even some of my faculty, Ralph Nader as a historical figure is an unknown.”

In his 45 minutes at the podium, Nader filled in a few of those blanks. Refraining from politics—he’s running again this year—he focused on the difference between charity and justice, and urged his audience to heed Cicero’s famous assertion that “Freedom is participation in power.”

“Charity has very important results. It helps people in their moment of need,” Nader said. “It also sensitizes the provider of charity. It broadens horizons, gets them out of themselves, and widens their frame of reference in life. But if we don’t move to justice, we will be left with the symptoms to deal with. And they will always grow faster than we can respond to them.

“Look at the food-help groups in cities now,” he added. “They’re running out of food for hungry people, at a fast clip. We’re the biggest agricultural granary in the world. What’s our excuse?”

One of our deepest shortcomings, he contended, can be found in citizens’ creeping alienation from those rights famously described by the nation’s founders as inalienable.

“Rights have to be linked with remedies,” Nader declared. “The right to go to court, the right to seek an injunction, the right to march where the constables don’t want you to march. These move rights into areas of dynamic action.”

But even remedies aren’t enough. “The next sequence is what I call facilities,” he went on. “Facilities are ways to make it easy for us to band together in our respective roles: whether it’s parents dealing with schools; whether it’s consumers of electric/gas utilities, and water services; whether it’s depositors in banks; whether it’s insurance-policy holders. That’s where we have failed, and that’s where most democracies fail.

“And the power structure knows this,” he continued, singling out corporate influence in the halls of government. “They know that they can give us rights. They don’t like the remedies, because they don’t like to be sued, but they have ways to keep that to a minimum. Where they can strike is to prevent us from having facilities.”

As an example, he cited laws in Illinois, Wisconsin, and California requiring utility companies to include inserts in their billing envelopes giving customers the option to band together to represent their interests before utility commissions in court. In 1993, one such consumer group got Commonwealth Edison to refund $1.3 billion in excessive charges in a settlement. Yet the Supreme Court has ruled such inserts unconstitutional, even when paid for by consumer groups themselves, arguing that a corporation’s “right not to speak” trumps other concerns.

Nader called for a “university requirement of civil practice” aimed at bolstering the ability of ordinary citizens to protect and advance their interests.

“How do you get legislation drafted? How do you get it through? How do you get a court challenge to be brought in a proper way with standing to sue? How do you start civic institutions?” Nader asked by way of outlining a curriculum. “That is something that one can study—we have strong civic personalities in our history,” he said. “But nothing can substitute for actual experience in the civic arena.

“When I speak to college students, to drive that point home I ask them, How many people have never been to a shopping mall? Nobody raises their hand. I say, How many people have never been to McDonald’s or Wal-Mart? Almost nobody raises their hand. And then I say, How many people have never been in a court of law as a spectator? Lots of hands go up. How many people have never been in a city council meeting? Lots of hands go up.

“Youngsters do not see that arena as part of their education. And as a result, the lack of understanding of it, the lack of familiarity, the lack of wanting to shape it—freedom is participation in power—it becomes the heritage of people who graduate from high school and college. And even, I might add, graduate school.”

Universities excel at the production of knowledge, Nader observed, but lag when it comes to putting it into practice. It is therefore no coincidence, he concluded, that “our country is full of problems we don’t deserve and solutions we don’t apply.”

Reflecting on the speech several days later, Dean Gelles said it had given him just as much food for thought as he hoped it would give everyone else. The SP2 student body may be in the field 250,000 hours a year, “but that does not rise to the level of what Nader means by full civil engagement,” Gelles said. “You can go to a field placement three days a week, but if you’ve never been to a city council meeting, that’s a problem. If you don’t know how a bill is really passed, that’s a problem. If you’ve never been to a Congressional hearing, or a mock-up, then you’re not seeing the world as it really works.” SP2 addresses some of these areas with its master’s of social policy degree, and the political science department offers a semester in Washington, but Gelles said that Penn students could be better served in this regard.

Indeed, that notion dovetails with what he hopes to accomplish by means of SP2’s centennial celebration, which will feature public lectures, panel discussions, and other events this year and next.

“We vie with Annenberg for the right to be smallest school at the University of Pennsylvania,” Gelles jested. “To be truthful, in the 60 years [that it has been a part of Penn], the school has had a reputation of marching to the beat of its own drummer. You could even go so far as to say that it was co-located at the University of Pennsylvania, but wasn’t necessarily part of it. And that really deprived our students and faculty of the full benefits of being at Penn: the ability to collaborate with the other 11 schools on campus, the ability to become involved with some of the social-policy and civic-engagement activities.”

Since becoming dean in 2003, Gelles has put an emphasis on strengthening SP2’s connections to other parts of the University. For example, the school now offers a dozen joint degree programs in collaboration with other schools and centers, including Wharton, the School of Design, and Penn Law. Gelles hopes the centennial will increase the school’s visibility and value to the rest of the Penn community. In that context, his choice of speakers for the kickoff event furnished an opportunity to reflect not only on SP2’s mission but on the question of how that mission might best be fulfilled. “Nader takes the position of being unwavering, stubborn, and unwilling to compromise. In my work, it’s almost always about compromise,” Gelles observed.

“It makes you stop and wonder,” he added. “Am I on the right side of this line?”

—T.P.