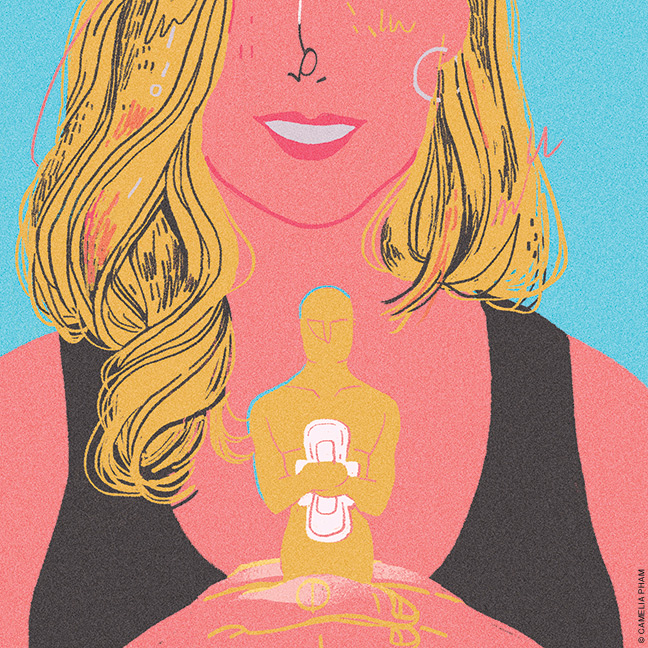

Penn student nabs an Academy Award—while raising “period poverty” awareness.

Claire Sliney C’21 needed to grab her sweater.

She was headed back into Hollywood’s Dolby Theatre to find it when she passed a sobbing Lady Gaga, who had just won the Oscar for Best Original Song. “Congratulations!” Sliney called out. Gaga thanked her, still crying, and continued on her way. Sliney got her sweater. Soon after, she flew back to Philadelphia and took a French exam.

It sounds like the start of a fever dream, but this very real story sums up what the past few months have been like for Sliney—a philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) major who has been balancing life as an Academy Award-winning documentary producer with life as a sophomore at Penn.

On February 24, about midway through the 91st Academy Awards, Sliney and the team with which she created Period. End of Sentence. rushed to the stage to accept their award for Best Documentary (Short Subject). As the film’s lead producer and director spoke their thanks into the microphone, Sliney and her two best friends—college students who, like Sliney, share executive producer credits for Period—showed their gratitude with joyful hugs and huge smiles behind them.

“That was just the most surreal experience, truly,” Sliney says, remembering seeing both Melissa McCarthy and Jennifer Lopez smiling at her from the audience. “It was a crazy role reversal to see the best of the best in Hollywood looking at us, cheering for us, excited that we won. That’s when we realized that we deserved to win.”

She suspects that the reason it all felt so strange—and why she and her team never imagined they’d be standing on stage together accepting an Oscar—is because they didn’t set out to make an award-winning film. “Our intention was never to get to the Oscars,” says Sliney, the first Penn student to ever win—or even be nominated for—an Academy Award while still in college. “It was to do the work we were doing and spread awareness as far as we could.”

Period documents a rural village in India where menstruation is simultaneously enigmatic and stigmatized, and where a new machine that makes low-cost sanitary pads arrives to provide local women with both necessary supplies and a new source of income. It was through Sliney and her friends that the machine got there.

Six years ago, as a freshman at the independent Oakwood School in Hollywood, Sliney joined a club focused on girls’ access to education. When Sliney and her friends learned that in some communities, girls were dropping out of school when they began getting their periods—and that someone had invented a low-cost machine to make sanitary pads accessible—they decided to take action.

“Period poverty and the stigmas around periods aren’t discussed very often,” Sliney says. “Realizing there was this issue that I had zero awareness of compelled me to learn everything I could about it.”

Extensive research and a series of partnerships led Sliney’s group to Kathikera, a village about 70 miles from India’s capital. Their club began fundraising through bake sales and backyard yoga fundraisers, and eventually executed a $45,000 Kickstarter campaign to fund “The Pad Project.”

At some point along the way, the idea of a documentary film came up. Coming from a private school in Los Angeles, minds went straight to movies the way they might to a book or viral video or website elsewhere. Plus, several of the kids’ parents had film industry connections.

More importantly, by creating a short film, “we thought we would reach more people and educate people all over the world about the work we were doing and what we had discovered,” Sliney says. Soon the project had a director—a recent USC film school alum named Rayka Zehtabchi—and other key production staff in place. Sliney watched as it “turned from high school lunchtime meetings once a week to becoming an actual, tangible project and an actual film.”

Sliney estimates that she’s seen Period in various iterations roughly a hundred times now—including the final 26-minute, Oscar-winning version that’s currently streaming on Netflix.

Aside from giving her opinion on various cuts, she also helped ensure that the story stayed authentic and accurate. “I think it’s really easy for projects—especially when they pertain to other communities—to not be conveyed properly,” she says. “A lot of the work I did was making sure that the content we were going to end up releasing was representative of the actual partnership and the work that was being done.”

She believes that authenticity also explains the documentary’s success. “There was never an ulterior motive,” she says. “The fact that high school students were able to come together and make an Oscar-winning documentary just goes to show that our commitment to the project was palpable.”

From actress Emma Stone at the Oscars to male friends back at Penn, Sliney says everyone who talks to her about watching Period. End of Sentence. sayshow much they loved it. She’s proud not only to have helped improve life for the women of Kathikera but also to have sparked a broader conversation about periods and the stigma around them.

Almost a full month after her Oscar win, Sliney says other Penn students were still flagging her down on campus to congratulate her. “For so long, this was such an individual project that I was working on with my Oakwood community and our partners,” she says. “To have people from my Penn community coming up to me has been so incredible.”

Interest in the Pad Project, of which she’s a cofounder, has also skyrocketed thanks to Period’s success. “Our email and website have just been blowing up,” she says. “Now that we have all this attention, we’re excited to harness it and do all the work we can moving forward.”

The Pad Project has already installed several more pad-making machines in other Indian villages, and Sliney says they are continuing to strengthen the infrastructure in Kathikera while also looking for new communities to assist.

While her experience with Period hasn’t changed Sliney’s own plans—she’s still pursuing a PPE major and gender studies minor—it has shown her how effectively film can help spread the political and social messages she cares about.

“I’ve never taken a formal film class,” the Oscar winner says, “but now I’d love to dabble in cinema studies a bit.”

—Molly Petrilla C’06