The first century of Penn’s alumni magazine

by John Prendergast

On November 14, 1902, the first issue of what is now The Pennsylvania Gazette appeared.

In a lot of ways it bore little resemblance to the current incarnation. For one thing, it had a different name: Olde Penn. And it wasn’t a magazine at all, but a newspaper, eight more or less tabloid-sized pages long, published every Saturday during the academic year and available by subscription for $1 annually or for 5¢ a copy. In other respects, it was pretty similar. The story lineup would be familiar to any current reader—articles on new campus buildings and an archaeological expedition, sports news, book reviews, etc. (For more details, please see “Decade by Decade.”)

The University was already a century-and-a-half old when its alumni magazine was born, but just 30 years had passed since the move to West Philadelphia. The creation of the campus we know today can be traced in the Gazette’s pages—along with some projects that fortunately never got beyond the drawing board, like the “University Tower” at 36th and Locust proposed in 1948. Along with that physical expansion came the University’s development into an institution of true national and international stature, with a faculty and student population to match. Perhaps most of all, the magazine is a treasure trove of information about Penn traditions and rituals, student attitudes, and daily life on campus over the course of a tumultuous century.

Though it’s admittedly a cliché, examining the back issues of the Gazette is like paging through an old photo album—a bit of embarrassment, quite a few surprises, and, mostly, fascination with all that has changed and stayed the same.

Here, some pictures from the album.

The founding editor was an enterprising graduate of the Law School named George E. Nitzsche L1898, who remained at the helm for most of its 15 years as Old Penn (the e was dropped by the second volume). Nitzsche’s position as editor was not constant—not surprising, since he was also the University’s Publicity Agent (later Recorder), and at one point served as Registrar and Bursar of the Law School. But Nitzsche was continually involved, and during his tenure, the paper evolved into a magazine format, with smaller dimensions and better paper stock, eventually numbering as many as 64 pages per issue.

It shrank from newspaper to magazine size in 1909. By then, in addition to extensive football coverage, photos of and articles about the many new buildings and academic departments, and letters from and notes about alumni, Old Penn also ran scholarly articles by faculty members and other leading thinkers, as well as accounts of archaeological expeditions, intercollegiate debates, and various theatrical productions.

In 1909, the magazine published two poems by Ezra Pound C’05 G’06, saying that “we are jealous of the fact that England should have discovered and honored his genius rather than his own native America, but we are duly proud of him as a son of Pennsylvania.”

Occasionally, campus events of national importance played themselves out in the pages of Old Penn, such as the politically-charged firing of an assistant professor named Scott Nearing C’06 in 1915, which eventually led to the development of the modern tenure system at the University. A 1913 article, “The Evolution of Moving Pictures,” included a series of photographs by Eadweard Muybridge, who had worked on his landmark study, Animal Locomotion, at Penn’s veterinary school in the 1880s.

June 24, 1916 marked the last issue edited by “George E. Nitzsche and members of the University staff.” The first issue of the 1916-1917 year didn’t come out until December 22, 1916. The cover was redesigned, with a list of “Leading Articles” and a sketch of Benjamin Franklin at the bottom. The new editor was one Edward R. Bushnell C1901, who (two weeks later) explained to puzzled alumni that “the University Trustees temporarily suspended the publication of this magazine, and it required more time to get it under way than expected. It is our hope that the new features introduced will make amends for those lost.” The first issue listed five ways that the magazine “aims to serve Penn,” including “To interpret editorially the spirit and attitude of the university and to strengthen the bonds between the University, its students, graduates and friends.”

Following America’s entry into World War I, stories of the many faculty and students serving appeared. In October 1917, Wharton Allen wrote, in “First Impressions of the War”:

“Life does not seem the same over here. I can’t explain it, for we are all changed men. We had been here only three days and had only learned the roads to our posts when the Germans started a bombardment. I hate to recall it. It seemed as if all Hell was let loose.”

(A note in the January 1, 1918, issue reported that the honorary degree awarded—in absentia—to Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany in 1905 had been revoked by the trustees.)

The Association of Alumnae, founded in 1912, used the need for trained personnel in wartime to press its case for admitting women “into all departments upon the same basis as men” in an open letter to the trustees: “Can you as a patriotic citizen and a Trustee of the University, refuse to hear the appeal of the young women for this necessary preparation? … We ask you to use your great influence in opening wide every avenue of instruction in the University to women on equal terms with men.”

Old Penn was born again as The Pennsylvania Gazetteon February 1, 1918, reviving the title of a weekly newspaper published by Benjamin Franklin from 1729-1748 (the dates still appear on our contents page with the copyright notice). “The reasons for the change of name will be immediately obvious,” the editor wrote. “The publication which represents the University of Pennsylvania should, if possible, carry its name, so that a reference to it will instantly call to mind the University itself. As The Pennsylvania Gazette, this will now be possible.

“Likewise, it has always been our conviction that Pennsylvania should overlook no opportunity to do honor to Franklin.” Under its new name, the editors wrote, “The Pennsylvania Gazette will redouble its efforts to serve the University and its alumni.”

The tradition of publishing interesting lectures and articles continued. In its second issue as the Gazette, a four-page article on “The Russian Revolution” by Dr. William E. Lingelbach of the Department of History included his own first-hand observations of the events of the previous year. The following month saw a lengthy article by Law Professor David Werner Amram titled “A Jewish State in Palestine.”

Though published for the alumni, the Gazette was not, strictly speaking, of the alumni until 1925. Before that, the magazine was published by the trustees of the University. With the 1925-26 volume, though, responsibility for the Gazette was transferred to the General Alumni Society, which already put out a monthly publication of its own, called The Alumni Register.

In the October 2, 1925, issue, the first under the new arrangement, an editorial noted that the Alumni Registerwould have its name changed to The General Magazine and Historical Chronicle (in imitation of yet another of Franklin’s publishing ventures) and would become a quarterly that “will endeavor to express the literary and scholarly attainments of Pennsylvania’s faculty and alumni.” The Gazette, meanwhile, “will continue to be a news magazine, although improved, we hope, by the added cooperation it will receive from its publication board and as the official spokesman of the Alumni Society.” GAS members would receive both publications with their annual dues of $5. (By then, the subscription price of the Gazette had tripled to $3, though a single copy was 10 cents, only twice the cost in 1902.)

In practice, the change of ownership had little impact. Bushnell continued as editor and the magazine continued to offer the same mix of University and alumni (mostly club) news, reports of faculty research and publications, and lots and lots of sports—especially football.

When Penn beat Yale 16-13 in the first meeting of the two schools since 1893, the victory was announced in banner type on the first page of the October 23, 1925, issue, and the Bushnell-bylined story began: “There have been many brilliant constellations in Pennsylvania’s athletic firmament, but certainly not within the last thirty years has any Pennsylvania eleven ever illumined the intercollegiate gridiron with such a bright light as the collection of stars that compose this year’s football team.”

The 1920s Gazette also included a regular student column—which, under several names and with occasional interruptions, has been a regular feature of the magazine ever since. These informal reports mixed discussion of sports and the round of campus rituals and more general essays. “The student body is at the present writing immersed in the sea of doubt and disaster known commonly as midyears. The greater portion of the campus is engaged in the pastime of stretching the minimum mental preparation over the maximum number of exam book pages,” wrote G. G. Gordon Mahy Jr. C’24 in one representative sample from the February 15, 1924 issue.

The University Museum’s archaeological expeditions continued to be a staple of the magazine’s coverage. In “Oldest Examples of Writing Uncovered in Babylonia,” published January 25, 1924, expedition director C. Leonard Woolley wrote about the resumption of work “in the beginning of November [on] the excavations at Ur of the Chaldees, which had been interrupted by the summer months. The most laborious task that is being undertaken is the clearance of the masses of debris surrounding the ziggurat, or staged tower.” The following month, “Museum Excavations Confirm Biblical Story,” dealt with the latest finds from the Beisan site in Palestine, “known in ancient times as Bethshean and mentioned in the Book of Kings.”

The year 1929—the 100th anniversary of Franklin’s Gazette—opened with the announcement of several changes at Penn’s magazine: “With this issue the GAZETTE appears in a new and distinctive dress, with an altered format and under new direction.” From then on, the magazine would be published “fortnightly” during the academic year and monthly in June, July, August and September.

“Editorially, the Gazette will seek, not merely to make itself a formal medium between the alumni and the University, but a link of living interest to all alumni.” The editorial promised more attention to athletics, and that articles by “well-known sports writers and coaches will appear throughout the year.” It also pointed to the color (blue) cover, explaining, “until the middle of the 19th century the ‘colors’ of the University were blue.”

Another story noted that, “in view of plans for an enlarged paper,” a “separate editor” for the Gazette had been hired: George Brian Hurff Jr. C’24. Before being promoted, he had been “Assistant Editor to The General Alumni Society publications,” which had put him in a good position to guide “the GAZETTE into new fields.”

Two years later, Hurff was gone—a casualty of the deepening Depression. The first issue of the 1931-32 academic year announced that the General Alumni Board “embarking on a policy of necessarily rigid economy,” had decided that separate editors for the Society’s publications was a luxury they couldn’t afford; one would have to do.

He was Horace Mather Lippincott C1897, who would remain as editor through 1945. Also apparently as a result of economies, the magazine abandoned the cleaner, modern three-column format adopted by Hurff and reverted to a more historical look, with two columns and colonial-style type for the title.

The University was tightening its belt everywhere. The December 1, 1931, issue noted the “general disturbed financial conditions of the country” in an article about tuition receipts and requests for financial aid. “Every effort has been put forth to make it possible for needy and deserving students to continue their courses … The aid funds have also been used liberally to tide students over periods of emergency. Unfortunately, these funds are not as large as they should be, even in normal times.”

Ten months earlier, on February 4, 1931, the magazine had printed the text of what became known as “the Gates Plan,” named for Thomas Sovereign Gates W’93 L’96 Hon’31 Gr’46, who had become Penn’s first president in 1930 (before that, the provost was both the chief executive and academic officer). The article described a reorganization of Penn’s athletic programs, replacing the alumni-controlled University Council on Athletics with a “division of inter-collegiate athletics” within the University. The section on football began: “The mere fact that football contests produce the bulk of the revenue required to maintain inter-collegiate sports will be regarded as little more than incidental, and not be used as the basis for the placing of exaggerated importance upon this sport, those engaged in it, or special treatment and concessions.” Among other changes in practice, “protracted ‘rest’ trips to resorts, involving considerable cost and of doubtful benefit, will be discontinued.”

The Gazette was a staunch supporter of the Gates plan and, more generally, pushed the idea that college was serious business and not “an amusement park.” As one of several editorials put it, approvingly, “Members of the faculty say that they have no longer any apprehension whatever about disorder or disturbance in the classroom.”

The Depression continued to cut into the Gazette’s budget. The March 15, 1934, issue notes that pages had been cut from 32 to 16 due to “lack of funds and reduction in the stock of paper purchased” and the following issue—mentioning that membership in the GAS had fallen from 9,771 in 1928 to 4,657 in June 1934—announced a 50 percent cut in the alumni publication budget, with no money for illustrations.

Finally, the July 1, 1937, issue announced that the magazine would be published 10 times yearly starting the next year. (In an October 1939 editorial on the limits of the magazine’s news coverage, Lippincott testily reminded readers to “Please remember that the Gazette is now a monthly, whereas it was formerly a weekly when the alumni more widely responded to its support.”)

Either Lippincott, who was also editor of the General Magazine, kept the best scholarly stories for that publication or budgetary exigencies limited coverage in the Gazette beyond regular departments for University, alumni, and athletic news. One innovation in the late 1930s was “Prominent Pennsylvanians,” the first regular section devoted to short pieces on alumni, aside from self-reported alumni notes. It was made up of four head shots and bios of men (almost always), defined by their profession.

The November 1939 issue included “Executive” William S. Palely W’22, the president of the Columbia Broadcasting System. The photograph shows him in profile, looking considerably more glamorous than the “Diplomat,” “Engineer,” and “Physician” with whom he shares the page.

Even as the University and the magazine struggled with the hard economic times, however, the Gazette was an enthusiastic proponent of an expensive, ambitious—and from this distance, strikingly wrongheaded—plan to create a new undergraduate college campus in Valley Forge, using land donated by an alumnus. The issue was first raised in the 1920s, and several Gazette articles reported on aspects of the plan.

In the early 1930s, the idea seemed to fade away—“Nothing but battered feelings and discouragement came of it,” sighs an editorial in the April 15, 1934, issue—but before long, in addition to verbal support in editorials, the Gazette was running numerous photos of the bucolic site, including a fold-out map with the crowded West Philadelphia campus on one side and the open spaces of Valley Forge on the other.

But dissenting views were also allowed, such as an editorial by DP Editor-in-Chief G.G. Della-Cioppa reprinted in the May 15, 1937, issue—which gives a vivid picture of the campus in the years before World War II:

But what has this Valley Forge plan to do with the present undergraduate body? We who are now attending the University will not be affected it is true, but we are perhaps more pointedly cognizant of present campus conditions than many of our alumni. We are living NOW with the flying waste paper of Woodland Avenue, the roar and rattle of traffic at all hours of the day and night. We must keep appointments with certain members of the English Department who are disgracefully housed in a dilapidated store. We are the ones who must contend with the eyesores which now dot the campus,—the repellent parking lot at 37th and Woodland Avenue, the shacks which serve as stores along 37th Street, the old dormitories familiarly known as the “barracks.” We know directly of the lack of a real Chapel, the inadequate facilities of Houston Hall which do not allow for a campus “commons.” Ancient boarding houses face fraternities; “beer joints” are just around the corner. Anything and everything uses our campus as a thoroughfare.

As the 1930s drew to a close, attention turned toward celebration of the University’s Bicentennial in 1940—increasingly, to the question of whether worsening conditions in Europe would force the cancellation of festivities. (In the end, they went off as scheduled.)

The January 1942 issue—the first after Pearl Harbor—includes a message from President Gates exhorting “each and every one of us at the University of Pennsylvania to stand behind the President and Congress.” From digging foxholes behind the University Museum (pictured on the cover for October 1942) to on-campus air-raid precautions and ROTC classes in hand-to-hand combat (“Here they learn how to break a man’s arm at the elbow with a maximum of certainty and dispatch and how to kill a man with your bare hands merely by grabbing a fellow by the head and snapping his spine.”), as the conflict deepened the focus shifted to reports of alumni in action, in letters dated from around the world—and to those who died in battle.

Among the most dramatic accounts in the magazine is “Thirty-One Days Adrift,” published in November 1943, the firsthand report by Midshipman Morton Dietz on his survival at sea after his ship was torpedoed by a submarine:

“On the eighteenth day the bos’n, who had been acting peculiarly, died and we buried him at sea. All during this time we prayed constantly, each man in his own way and in any prayers that he could remember.

“After the bos’n death many of our shipmates followed him. Of the 24 men who started out in our lifeboat, only eight finally managed to reach safety.”

Other accounts included fighting in the Libyan desert, in the Philippines, and on Iwo Jima—and from Munich, Germany, where Captain Joseph T. Marnell D’43, quartered in Hitler’s private apartment, wrote a letter to his wife on the Fuhrer’s stationery. He also reported finding two wine bottles from the Spanish dictator, Generalissimo Francisco Franco, on Hitler’s desk.

“War’s End Comes With a Bang,” was the headline in September 1945, following the announcement of Japan’s surrender in August. “Joined by thousands of celebrating townspeople, the students staged an old-fashioned ‘Rowbottom’ for more than two hours at the intersection of 37th Street and Woodland Avenue.” (“‘Incendiary Bomb’ Falls on Familiar Corner” reads the caption of a photo showing a blazing crate and stalled trolley and car traffic.) The crowd was dispersed by the use of firehoses and police who “gently tapped a few heads with their nightsticks.” Following a special chapel service a few days later, “Many of the undergraduates quietly left Irvine Auditorium with the realization that for the first time in their college careers America was no longer involved in the holocaust of war.”

A few months later, the March 1946 issue carried a story about war project PX, better known as ENIAC: “Fabulous wonder brain designed and constructed at the University’s Moore School for the Ordnance Department. Mathematical robot is the first all-electronic general purpose computer ever to be developed,” noted the subhead to a more sober article on the device.

The 1940s would be Penn’s last hurrah as a national football power. In January 1948, the Gazette published a retrospective piece, “The Munger Coaching Decade,” by Edward Bushnell, by then editing The Franklin Field Illustrated. Noting that he’d seen his first game in 1899, “With no intent to make unfavorable comparisons with any of the ten able coaches preceding the present regime, it is my conviction that … the present coaching staff has made a record which is certainly without a parallel in Pennsylvania’s football history.”

In November 1946 “‘Old Penn’ is Bursting at the Seams,” reported on the intense crowding as returning veterans and recent high-school graduates packed campus restaurants and classrooms, fighting for scarce seating space in the library and parking spaces along curbs and in lots. Two years later, the Gazette reported on the release of expansion plans that included the closing of five blocks of Woodland Avenue, construction of several new structures, and razing of others. The University’s recently appointed president, Harold E. Stassen, called it “a plan for a generation” and the Gazette article described the changes as “the most ambitious since the University established itself on the present site in 1872.”

Lippincott had retired as editor in April 1945. His successor, Leonard C. Dill Jr. C’28, who was also business manager and general secretary of the Alumni Society, was still in the editor’s chair in 1951-52, when the Gazette marked its 50th anniversary with a new cover design and a series of articles “describing the history and development of a facet of the University since the turn of the century.”

But elsewhere in the Gazette, the focus was on the future. In the post-war era, the University’s role in a Cold War intellectual competition with the Soviet Union was a running theme, especially after atomic physicist Dr. Gaylord P. Harnwell, then chair of the Physics Department, became Penn’s president in 1953. Typical of a series of presidential reports the magazine would publish during Harnwell’s 17-year presidency was “Our Future in Science,” in January 1955. It used the occasion of the opening of the new Physical Sciences Buildings to detail Penn’s plans to “achieve a stature in scientific fields comparable to that of the great technical schools.”

The November 1958 issue introduces a Gazette “new in format and larger in scope”—the result of the folding into the magazine of the old General Magazine and Historical Chronicle. New features included a redesigned contents page and the first color cover illustration—of (who else?) Benjamin Franklin. Two columns from the General Magazine—“The Case for Books,” by Charles Lee C’33 Gr’55 (which would continue well into the 1960s) and “Gazebo,” a miscellany by Ruth Branning Molloy Ed’30—also found a new home in the Gazette.

Following Penn’s entry into the Ivy League, the football team’s fortunes had suffered, to put it mildly. (See “Harold Stassen and the Ivy League,” November/December, and “Letters,” this issue). The February 1959 issue wistfully announced that Penn would no longer play Navy, adding that, with the earlier dropping of Penn State from the schedule, “Navy stood as the Red and Blue’s last link with its big-time past.”

In the late-1950s, Thomas G. Harris C’49 and William Schramm C’54 G’57 served a few years each as editor. In 1960-61, Robert M. (“Dusty”) Rhodes was hired—the only non-alumnus to hold the post. Under Rhodes, the Gazette consistently began publishing magazine-style feature articles, profiling faculty, students, and alumni. Even more striking is the way he opened up the magazine visually. Rhodes put a strong emphasis on an eclectic mix of documentary-style photo essays that showed readers what was happening in the various corners of campus. They ranged from the self-explanatory “Afternoon Walk on Campus”; to “The Architect and the Building,” on architect Eero Sarrinen and his design for Penn’s new women’s dormitory, Hill Hall; “The Crew Gets Ready,” on the 107th year of rowing at Penn; “Visiting Professor Arnold Toynbee”; and “Pennsylvania’s Legislators.”

Through the decade, the magazine would report on the tension between tradition and change at the University. In October 1961, the Gazette ran the obituary of its first editor, George E. Nitzsche. The cover story of the following issue was on the 15th anniversary of ENIAC, in which it was noted that “in less than a human generation computers have developed from laboratory curiosities to highly sophisticated systems with a universality of applications … in mid-1961, there were 5,371 computers of all types in operation.”

In May 1963, “another tradition of long standing bit the dust when the Ivy Day ceremony, since its inception a male-only affair, became coed,” the subject of that issue’s cover. “Tradition held, however,” the accompanying article added encouragingly, “for the other annual year-end program: Hey Day remained segregated” with separate programs for men and women.

The following year, in March 1964, the Gazette ran a special section on education for women at Pennsylvania headlined: “It’s Agreed: The Coed is Here to Stay,” which included portraits of “Six of CW’s 1,283” photographed by a young photographer named Mary Ellen Mark FA’62 ASC’64 Hon’94. (The editor’s column explained that “she wants to be a magazine photographer,” and concluded prophetically, “I think she just might make it.”)

In 1966, “Pennsylvania’s 6,981 undergraduates”—by then, 2,253 of them were women—“made headlines by electing Barbara Berger the first woman president of an Ivy League student government association.” The article in the February 1967 issue added that the election “brought publicity in no less than 25 newspapers and signaled the beginning of a new role for women on the Pennsylvania campus.” In 1969, the Gazette profiled the first woman editor of the DP, Judith Teller W’71, and, in 1972, the first woman to head the General Alumni Society, Ione A. Strauss CW’54.

Literal walls were coming down on campus, too. The November 1964 issue included a map showing “What’s New Since 1952,” from Dietrich Hall, completed in 1952 to the Richards Medical Research Building (1960), Van Pelt Library (1962), and Locust Walk, which had opened the previous month.

Several new residence halls were rising on land cleared between 38th to 40th Street, dubbed “Superblock.” The resulting destruction of neighborhood housing and businesses would have lasting effects on the University’s relations with the community, but the Gazette celebrated the three new high-rises with “A Skyline of Our Own,” in November 1969.

The October 1964 issue recalled the War on Poverty with a story on a “Six Weeks’ Summer Session—with a Difference,” that described a project in which “one hundred high school dropouts” helped build four playgrounds in West Philadelphia. In December 1965, there appeared the obituary of the first Penn alumnus “as far as we know” to be killed in Vietnam, helicopter pilot Captain Charles F. Kane C’59.

A year later, the campus experienced what the Gazettecalled College Hall’s first “sit-in,” which lasted three days. The protest was over two “Federal government sponsored chemical-biological warfare research contracts at the University,” known as Spicerack and Summit. More sit-ins would follow in 1969 and 1970, prompted by the bombing of Cambodia and the Kent State killings. By then, President Harnwell had announced his retirement.

His replacement, Martin Meyerson, then president of the State University of New York at Buffalo, was featured in a decidedly low-key cover story in October 1970. “It was 8:15 on the morning of September 1 when Martin Meyerson arrived at College Hall for the first day of his new job.” Titled “New Man in College Hall,” it showed the new president in meetings, having lunch with a racially mixed group of students in Houston Hall, and touring the campus.

There was a new man at the Gazette, too. After a decade as editor, Dusty Rhodes was moving to Providence to edit the Brown Alumni Monthly. Publisher and business manager Michel T. Huber W’53 ASC’61 praised Rhodes for “editing a magazine which reflected the excitement of the 1960s as Pennsylvania grew in stature during the Harnwell era. And as difficult times descended on higher education in recent years, The Gazette reported with balance the manner in which Pennsylvania met its problems.”

A story announcing Rhodes’ successor, Anthony A. Lyle C’61, began by noting that, while editor of the DPin 1961, he had written that the Gazette “is not bringing a true picture of student life to its readers and has a two-word motto: ‘Avoid controversy.’”

Which is not an accusation ever raised against the magazine during his 25 years at the helm.

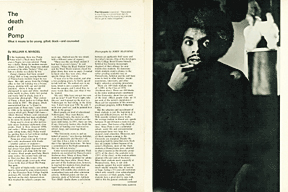

Under Lyle’s editorship, the Gazette enthusiastically continued and expanded its coverage of current issues such as race relations and drugs on campus—in articles like “The Death of Pomp,” in March 1971, on blacks at Penn. The reference is to a College Hall janitor, who “used to clean up after particularly messy freshman/sophomore class pranks (back in those innocent 1890s and earlier).” “Drug Story,” in the following issue, was about a Penn-student heroin addict enrolled in a methadone treatment program. Later, the magazine would tackle feminism and women’s studies, gay and lesbian issues, religious belief, and other hot-button topics.

Visually, the Gazette of the 1970s and beyond widened the magazine’s palette from the documentary photography favored by Rhodes to include striking graphics as well by an assortment of gifted artists, including Sam Maitin FA’51, Arnold Roth (see page 38), and a host of others. The magazine’s writing gained in power, too, thanks to a series of talented staff writers and the freelance contributions of alumni, faculty, and other writers.

By December 1973, a student columnist was writing about the “new old days”—that is, the 1960s—and an October 1975 article on conservative students asked, “Can You Trust Anybody Under 20?” The clock was hardly being turned back, though. A February 1965 article on undergraduate regulations seems to be edging toward the notion of personal responsibility, but a sidebar on “The White Bible” of women’s regulations notes that non-freshman women “may be out until 12 midnight without a late leave, if accompanied.” By the end of the 1970s, the Gazette was running a jokey article on a show called “Roommates,” broadcast on UTV (the student television station) and modeled on the Newlywed Game, that took male-female student cohabitation completely for granted.

The same issue that had announced Martin Meyerson’s selection as president also carried a story on the University’s “fiscal crisis.” Protests over tuition increases (on the order of $300-$400) became an annual event, and class size was increased as well. Nixon’s resignation, the energy crisis, and the U.S. Bicentennial (for which, in June 1975, the Gazette published the Declaration of Independence in Esperanto) also make appearances, along with Transcendental Meditation, “Jews for Jesus”—and, of course, streaking.

In sports, basketball took center stage. The team’s trip to the Final Four in the NCAA tournament in 1978-79 was perhaps the biggest story of the 1970s. An article on Title IX, “Beyond Adhesive Tape,” in March 1975, pointed toward the future growth of women’s sports: “A new federal act may put some muscle into the cause of women athletes.”

Some articles from the close of the decade sound a distinctly contemporary note, having to do with the Iranian revolution and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The December 1979 issue includes a brief story on student reactions to the takeover of the embassy in Tehran. “Shouting ‘Nuke Iran’ and directing obscenities against Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a group of an estimated 150 students rallied in Blanche Levy Park in front of College Hall to protest the seizure of the Americans at the United States Embassy in Teheran last month.” After the Justice Department ordered Iranian students to report to the INS, the article noted, the University notified 115 students to do so. That June’s cover story was an interview with two of the Iranian students occupying the embassy.

When Meyerson announced his decision to step down in 1979, the trustees ultimately selected Tulane University President Sheldon Hackney Hon’93 over campus favorite Vartan Gregorian, then the provost and before that dean of the School of Arts and Sciences. Hackney entered office amid controversy concerning that decision and would leave College Hall 12 years later—to head the National Endowment for the Humanities in the Clinton Administration—in the middle of a national furor. The issue then was the University’s handling of what became known as the “Water Buffalo Incident” and the trashing of 14,000 copies of The Daily Pennsylvanian by a group of black students.

The Gazette covered the 1981 and 1993 events, along with other battles—over divestment from South Africa, race relations, feminism, homosexuality, the role of fraternities on campus, morality, pornography, and as a special issue in February 1994 put it “The Great PC Debate.” The magazine also sparked some controversies itself, by running photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe and Sally Mann, and work by Andres Serrano.

In sports, an article in 1981 asked whether the new football coach, Jerry Berndt, “can do it”—this after his first two games (a 29-22 win over Cornell and a 58-0 drubbing by Lehigh). The answer, it turned out, was yes. The December 1986 issue reported on the Quakers fifth straight championship and 10-0 record, only the fifth undefeated season in Penn’s 110 years of football.

The nomination of Judith Rodin CW’66, then Yale’s provost, as Penn president—the first woman to hold the office and the first Penn graduate since Thomas S. Gates—was announced in the December 1993 issue. In the same issue: a student column on a popular new method of communication—electronic mail!—and a note that the University was lifting restrictions on investments in South Africa, in line with the wishes of Nelson Mandela.

A year after Rodin’s formal inauguration as president, the October 1995 issue reported on Penn’s #11 ranking in U.S. News & World Report, “its highest ranking ever.” The Gazette’s November issue featured Annenberg School for Communication Professor Larry Gross on the cover, and also reported on campus reactions to the “not guilty” verdict in the O.J. Simpson murder trial.

In the space usually taken by the editor’s column, “So It Went,” there was instead a column by Senior Writer Samuel Hughes that began: “Earlier this month, on a wet, raw morning, Anthony A. Lyle, ’61 C, called us into his office and informed us (in a voice not entirely devoid of emotion) that after 31 years of service to Penn, 25 of them as editor of this magazine, he was retiring.”

After an issue put out by the staff, Marshall A. Ledger, who had been a Gazette staffer from 1976-1987, stepped in as acting editor. That spring, a new permanent editor—only the 10th in 100 years—was announced to take over as of October 1996: Me.

Over the past five years, we’ve continued to report on Penn’s achievements as an institution (among others, the University’s rise in the U.S. News rankings to #5 as of 2001) and the accomplishments of faculty, students, and alumni, while also reporting fully and fairly on less positive news as it arises—and to receive our share of praise and complaint from readers. We’ve tinkered a bit with the design of the magazine, added some new departments, and continued to attract gifted writers and artists—alumni and others—to our pages.

The Gazette’s frequency, which had been eight issues yearly since 1972, was changed again in 1998, this time to bimonthly (combined with an increase in total pages beyond that in the old schedule). This issue of the magazine will go to about 140,000 alumni around the world, plus another 5,000 or so here on campus. In 1997, we established a Web site (www.upenn.edu /gazette), which includes the current issue’s contents and back issues since February 1997. (You’ll also find some special Centennial-related features there through the year, starting with the complete texts of issues from each of the magazine’s 10 decades.)

By the time the Gazette celebrates its 200th year of publication, there’s no telling what form it will take, but it seems likely that there will be some means of communication to connect alumni with the University and each other.

That first issue of Olde Penn did not include a statement of purpose, but following the summer break, at the start of the second volume, a front-page editorial sounded a note of celebration:

“We desire to take this opportunity of thanking our friends, and of expressing the hope that their interest will continue to grow, and that we may count upon their co-operation in our efforts to make the paper invaluable to those connected with the various departments, and of interest to every alumnus of the University of Pennsylvania.”

After noting growth of more than 300 subscriptions over the summer, “many from remote parts of the country and some from abroad,” the editorial continues, “So gratifying an increase, following the first year of publication, proves the interest of the Alumni in a paper which is endeavoring to present as accurately as possible the news of the week.”

Which is still our goal.

And we’re still grateful.