Contrary to his reputation, the writer was a warm, generous man—an exceptional friend in a time of trouble.

BY JILL HABER PALLONE

The writer Philip Roth, who died in May [“Obituaries,” this issue], taught creative writing and comparative literature at Penn in the 1960s and 1970s. An additional reminiscence of Roth in the classroom can be found here.—Ed.

His death hit me like a punch in the face. I suppose I had assumed he was immortal. He had been a presence in my life and mind for over 40 years, beginning with my last undergraduate year at Penn.

Much has been written about his challenging brusqueness and impatience, but the Philip Roth I knew had another, very different side.

There were about seven of us in his creative writing class. We felt like the chosen ones, for he spoke to us as familiars, as coconspirators in the counterculture of “bookishness.” We were in on his fascination with Kafka, his wry contempt of Nixon the trickster, even hints of his troubles with his first wife. And, of course, we talked about writing.

My friend Georgia and I were often invited to lunch with him at La Terrasse, which in the early 1970s was seen as the one place on campus fit for people like him. Most of what I remember is laughing together. And his jokes about how little I ate became a leitmotif that lasted years.

When the fall semester ended, he went back to New York and Connecticut to face his real work. But he and I kept in touch by mail. He supported me as I tortured myself over decisions about graduate school, then my difficulties at Stanford University, studying in the writing department.

I was an anxious mess, and as time passed, my condition got desperate. Stanford felt utterly foreign, and my intimations of psychic collapse translated into a stunning terror of earthquakes. He consoled and encouraged me, writing, “I remember my own lostness when I first got out to Chicago to be a graduate student, so I sympathize with your current plight. If it’s any consolation, I feel now I should never have left the South Side of Chicago, which turned out to be the only neighborhood to which I still feel connected, outside of the square mile I grew up in in Newark.

“Keep writing—you may wind up being more rooted to that than to any place. I hope things get better; I would think they will.”

They didn’t, and he was there for me again when I fell apart and flew back to Philadelphia, sobbing all the way, and was placed immediately in Penn’s hospital psych ward. Trapped in a haze of thorazine, nothing heartened me more than the kindness of his unexpected visit. My parents, also visiting, were shocked that the author of the reputedly salacious and “anti-Semitic” Portnoy’s Complaint (which they’d never consider reading) could be this warm, generous guy.

Philip and I kept writing through the nightmare years of my living back at home, then entering graduate school at Penn, still paralyzed by both anxiety and pharmaceuticals. I would be moved to tears by a package from him containing the gift of a colorful scarf, or his most recent book, inscribed with a written chuckle.

I felt I was a shadow of my former self. I felt slow and dull and entirely uninteresting. Still, he continued to invite me to sit in on his comparative lit classes (he had had enough of teaching creative writing by then) and sometimes back to La Terrasse. He would write, “I’d be delighted to see you in class or out. I do hope you come along and the nicest surprise for me would be to see your face.”

I managed, barely, to finish graduate school and was poised for even more trouble. Now, for various reasons, I was off of all medication and without a psychiatrist, and as numbing as the antipsychotic drugs had been, life without them was to become even more disabling. If I had shuffled through my days before, now I was running madly in circles. I didn’t eat or sleep, and I fell in love with self-destruction. Philip was one of the few sympathetic people in my life.

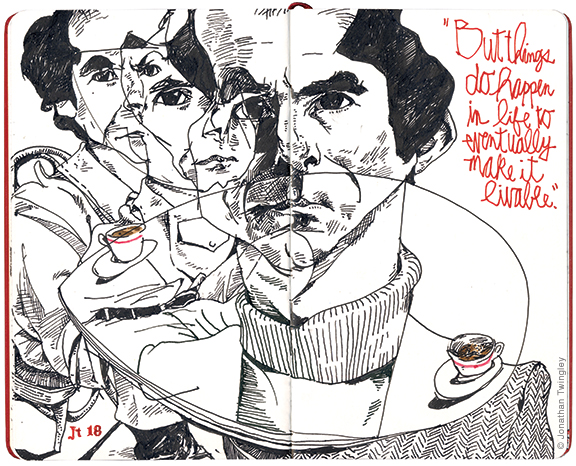

He wrote from London, “I’m not happy at all to hear of your rough times. They sound awful, yet your capacity for renewal is somewhat staggering. You do come back. Don’t try to kill yourself again, though, will you? At least not till I get back. It just isn’t the solution—not that endless pain is. I don’t underestimate the pain one bit. I’ve had a little touch of it and I can imagine what the full-scale thing is like. But things do happen in life to eventually make it livable.”

And when my parents, friends, and even strangers had taken to blame me for being so impulsive and difficult and I felt like a bad seed, he said, “No more homilies. Just my affection from afar, and my hopes for you, and a reminder to you that you are not a forgettable person, and that I for one regard you and count you as a friend, though a young one and a distant one, for the best of reasons.”

I clung to his encouragement even as I hallucinated and screamed in public places. And as fall became winter, I just got crazier and more self-destructive. In his next, long letter, Philip expressed alarm and urged me to get long-term hospital care and a good doctor. With my annual psychiatric hospitalization coverage completely exhausted, that was hard to do.

But I came up with an idea. Scream therapy. That appealed to me, for obvious reasons. I was bellowing my rage anyway; why not go somewhere where that was just the thing?

As ill-advised as that scheme seemed later, I was now obsessed with going to the Casriel Institute in New York, run by Dan Casriel, a slightly megalomaniacal former psychoanalyst turned psychiatric maverick. Inevitably, letting it all out without proper support or processing led me only to greater mental chaos. But I kept Philip well-informed, writing scores of wordy letters in an acceleration that matched the way I walked. He took it in his stride and with typical, blunt humor, “Just got back from my travels on the continent to find some two or three thousand letters from you … All those letters signify that you have not run out of words! Which is good. Talking is living too, you know. The grave’s a fine and private place/But none I’m sure do have there air mail stamps. Poetry.”

Realizing though that I (and he) could stand a change from my babbling on about my sorry state, one day he proposed an alternative: the “Underground University!” He would assign me books to read, I’d write to him about my thoughts and impressions (however bizarre they may be), and he would respond with his thoughts about mine. The first assignment, which I grabbed on to for dear life, was Solzhenitsyn’s novel Cancer Ward. Philip didn’t think there was any point in shying away from dismal topics.

I finished the book in two days, then scribbled god knows how many pages and sent them off to him in London. I opened his return letter with giddy excitement, only to read funny—and frustrated—comments about how my report had been entirely illegible, due to my microscopic handwriting. Thus, the sad, premature demise of the venerable UU.

Then there was the dramatic demise of my “scream experiment.” In a frenetic escape, I returned to Philadelphia, and after an especially serious suicide attempt, finally got the long-term hospital care Philip had advised all along. Years of struggles and hospitalizations followed.

But things do happen in life that eventually make it livable. I eventually found a psychiatrist who, with her saintly patience, intelligence, and compassion, changed everything. I found a miracle of a man, to whom I’ve now been married for 33 years. We live happily in Switzerland, where I continue to write poetry, grateful for the joy the process brings.

I’d been out of touch with Philip for a long time when he died, but I thought about him often. Many times I considered writing him again, to let him know how deeply thankful I have always been and how I really, truly did “come back.” But I worried about being a bother, remembering guiltily the “thousands” of letters about myself that I’d sent him long ago.

It was only after his death that I pulled out his letters to me and reread them, reminding myself of how exceptional a friend he had been. And now, I’m afraid, I’m too late.

Jill Haber Pallone CW’73 G’76 GEd’77 is a writer living in Lugano, Switzerland with her husband, Robert Pallone C’77 G’83. Her book of poems, I Am Not Myself Today, will be published this fall (www.jillpallonepoetry.com)

Jill, I too remember lunches with Philip Roth at La Terasse . Like you, I thought often of writing him but was worried too that I would be a bother. Would love to hear more from you. In NYC now and still married 44 years to another one of our classmates in Roth’s class, Bill Pollak. Philip Roth was a caring teacher, kind and supportive —and especially compassionate about your struggles. Thanks for writing this article. Georgia Brown Pollak CW ‘73

Beautifully and sensitively written, Jill. It is painful to hear the full extent of your torments; it is also glorious to read of your beautiful friendship and correspondence with your mentor. You clearly captured a place in his heart. How amazing! Thank you for sharing these raw memories. I am utterly captivated by your writing. –Sue Smith, CGS’94, GGS’03

Sono molto orgogliosa di te Jill! Grazie per la preziosa amicizia , ti voglio bene! Desi

I love this too. So generously written — and such a sensitive portrait of Philip, especially his generosity to anyone trying to write. His dry wit is there too. I still think of him when I confront a blank page, trying to think of what to say and how to say it.

Love this, Jill. (I’m an old friend of Mimi’s and a Penn alum.)