The biggest buzzword in disability rights is undermining intellectually disabled people.

By Amy S. F. Lutz

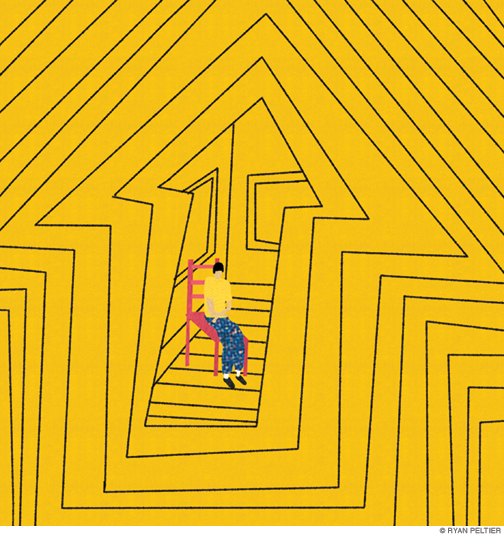

When my severely autistic son, Jonah, was first diagnosed at the age of two, we were so hopeful. How lucky we were, to live in the 21st century! Instead of being institutionalized in snake pits like Willowbrook, Jonah and his intellectually and developmentally disabled peers now had the right to educational, vocational, and residential services in “the community”—the biggest buzzword in disability discourse for the past 50 years. It all sounded so warm and fuzzy—until Jonah broke a teacher’s nose when he was in kindergarten and it quickly became evident that his cognitive and behavioral challenges would require intensive, specialized services. Over the years, these have included autism schools, special needs summer camps, and now, having just turned 21, a disability-specific day program. Although Jonah is thriving, his future is still terrifyingly uncertain. Disability rights advocates are fighting to close such programs, as well as others—like sheltered workshops, farmsteads, and campuses—they consider not in “the community.” It wasn’t until I returned to Penn to pursue my doctorate in the history of medicine, seeking to better understand the trajectory of these debates, that it occurred to me to ask: What, exactly, does “community” mean, anyway?

This is neither a rhetorical question nor an example of academic hairsplitting. Consider this statement by the National Council on Disability: “Living independently and in the community are preconditions for the enjoyment of human rights by people with disabilities and represent core values of the American disability community.” In the first use, community refers to a geographical location, like a neighborhood. In the second, it means a group of people that share certain characteristics, even if they don’t know each other.

There’s yet a third meaning, one that goes back to the beginning of community-based services. During World War II, psychiatrists discovered that soldiers suffering from shell shock—what today we would call post-traumatic stress disorder—were much more likely to recover if, instead of being separated from their units and sent to distant psychiatric hospitals, they were permitted to stay with their comrades. This conception of community—a set of meaningful relationships—would prove influential in civilian practice after the war.

Ideally, community would fit all of these definitions: a local neighborhood filled with like-minded people who really knew and cared about us. This is the romanticized version offered by disability rights advocates such as Ari Ne’eman, founder of the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network (ASAN), who has described the owner of a pizzeria who called to check in on an autistic man who typically ate in his establishment every day, but who had missed several meals due to illness.

Such moments of kindness doubtlessly occur—along with many complaints from the neighbors of autistic individuals banging their heads against the wall at 2 a.m.; NIMBY protests over the location of group homes; and, mostly, profound indifference. Today’s actual US communities are made up of strangers: according to economist Brian Bethune, 50 percent of Americans don’t even know their neighbors.

As these different meanings of community have unraveled, disability rights activists have latched on to place as the one that matters most. In a joint policy paper, ASAN and several other self-advocacy groups argue that “genuine community happens in inclusive, diverse and mixed neighborhoods” populated by “people who don’t have disabilities, and this does not mean staff.” Day habilitation centers, gated communities, clustered group homes, and virtually all settings that serve more than four disabled people at one time are emphatically rejected as “not community.”

The perverse result is evident in a comparison of two sample days at real programs currently serving intellectually and developmentally disabled (I/DD) clients:

Program A: Client spends the day feeding horses, collecting eggs, and picking tomatoes at a farm-based program. At lunch, he joins 32 peers for a meal they have helped prepare using ingredients produced at the farm.

Program B: Client spends 1.5 hours in a van with two peers and one direct support professional (DSP) driving to a mall 70 miles away. The group walks around the mall for two hours, buys nothing, then returns.

According to an increasing number of policies, only Program B is considered “in the community.” In a statement issued last year, groups including The Arc, Autism Society, and others urged Congress to pass legislation stipulating that disability services funded through Medicaid be “provided in the community in inclusive and integrated settings.”

At the state level, many agencies have already moved to restrict disability-specific settings like Program A—either prohibiting them outright or creating nearly insurmountable financial obstacles, such as reimbursing “community-based” programs, like Program B, at a much higher rate. These sweeping policy changes often fail to acknowledge the challenges experienced by many I/DD adults. The very behaviors that preclude many of them from participating in the supported work programs overwhelmingly favored by Disability Rights advocates—such as aggression, self-injury, property destruction, and elopement, all of which Jonah has suffered for much of his life—also make many public spaces inappropriate or even unsafe. Program B is just one example of the logistical contortions many providers go through to meet community requirements for their most impaired clients. The mall—wide-open and not very crowded on weekday mornings—is fairly safe. But a trip to the local mall won’t take up nearly enough of the day, so staff members are directed to drive to the mall five towns over.

The same fight has unfolded over residential settings. Consider these two programs:

Program A: An apartment building for autistic adults in a major city. Rent payments include a suite of supports, including life skills and vocational training. Social skills are practiced during scheduled events, and more informally in communal spaces such as a gym, swimming pool, and game room.

Program B: An individual apartment in the same city. Client lives alone, supervised by rotating DSP staffers paid $10.50/hour.

As a parent, nothing scares me more than Program B. My son is intellectually disabled and minimally verbal, so he could never tell me whether he spent his morning hiking through a state park, or whether his aide opted to let Jonah sit at home all day, watching the same 30-second clip of “Big Bird Doesn’t Fly” over and over again on his iPad. I also think Jonah would be safer from abuse—a scourge for I/DD adults—in a larger setting, with many eyeballs on him. Nevertheless, Program B meets the criteria of even the states with the strictest inclusion requirements, but Program A was the target of a campaign by ASAN to keep the state of Arizona from supporting it.

Jonah loves going to restaurants and amusement parks, and shopping at Big Box stores with his father on the weekends. But, importantly, the physical community is a means to many ends, including pleasure, fitness, and employment. The mistake advocates make is treating community as an end unto itself, and collapsing all the diverse factors that make life meaningful into that narrow measure.

A better policy would focus on maximizing ends: happiness, health, safety. Perhaps most importantly, interpersonal connection.

Disability rights organizations have rallied advocates, academics, and many policy-makers around the flag of community, to the point that virtually all services have come to be judged by this single standard. But the reason community has resonated so deeply with so many stakeholders is because the word still carries connotations of warmth and connection—even if, in practice, it now solely refers to a geographic location. Perhaps we need a new set of terms: public space or commons to describe the brick-and-mortar buildings where those of us with and without disabilities may or may not live, work, shop, eat, and play; and social network when speaking of the number and strength of the relationships that sustain us all. Too much is at stake to build our disability infrastructure on a foundation as amorphous, imprecise, and misleading as community.

Amy S. F. Lutz C’92 is the author of We Walk: Life with Severe Autism (Cornell University Press, 2020).

Thank You so much for this article!! Sometimes I feel that my thinking goes against the so called “best practices” that now dictate how programs and services need to be run and how people with I/DD need to be treated. The movement supported by Federal & State statutes, agencies, and advocates is to reject anything that is disability specific. How refreshing and reassuring to know that others feel as I do! This section of the article sums up my feelings: “As these different meanings of community have unraveled, disability rights activists have latched on to place as the one that matters most. In a joint policy paper, ASAN and several other self-advocacy groups argue that “genuine community happens in inclusive, diverse and mixed neighborhoods” populated by “people who don’t have disabilities, and this does not mean staff.” Day habilitation centers, gated communities, clustered group homes, and virtually all settings that serve more than four disabled people at one time are emphatically rejected as “not community.” ” Adhering to this model disregards the ability, and need of individuals to access the most appropriate, and often the most successful, approaches. It does not mean total isolation and exclusion from settings with people without disabilities. Rather it promotes the inclusion of people in the community while still providing the safety and supervision, along with the happiness and sense of belonging that their preferred relationships provide. My adult daughter has Down Syndrome. She lives in a 4 person group home in a regular residential neighborhood in our town. She attends a day program with other adults with I/DD. She works in 2 community settings with a job coaches. But her’s the thing. She has worked at one of those settings for 20 years. Everyone knows her and it is a great working environment, where she has very appropriate, very positive, very friendly working relationships there. But in 20 years she has never been invited to take part in any social activities outside of work. Not once. But with her peer group she is active and engaged as she frequently participates in community as well as in disability specific activities. Her group home setting andher day program settings are very well suited to address many of her needs. Also she spends a lot of time participating in community activities in community settings, with home as well as day program support. She is happy and engaged and productive! The goal must be to provide the settings where the individual will most successful in every aspect of life. Not to force them to conform to someone’s idea of how their life is supposed to be.

There should be no single idea of what is appropriate for any one individual. I live in a suburb. My sister prefers rural areas. My parents prefer the city. Are 2 out of 3 of us wrong, and needing an intervention or a policy to support our access to a more ‘appropriate’ residence? There are individuals out there that would prefer to live alone, and some that would like to live where they can connect with neighbors.

I appreciate the voices that self-advocates have brought to the table, but their opinions and perspectives are still just that.

I am a divorced, Midwestern woman. I do not presume to speak for every divorced, Midwestern woman.

What about people with anxiety? Should we expect them to be forced into a social situation that we consider inclusive? Most often, we don’t have that expectation. Why are we expecting individuals who often experience anxiety as a co-occurring condition, oftentimes alongside a host of other diagnoses and challenges, to a higher standard of inclusion?

I am leaving out the label/diagnosis on purpose. We need to value an individual’s preferences [both expressed and observed] over a policy.

I found this article useful for so many people whether it is a personal essay or a scholarly article. I work with individuals with severe and profound multiple disabilities. We have no “community” programs for them after completing high school. It is difficult to address transition plans when there are none or very limited post-secondary opportunities. While working on my master’s degree a few years ago, I was astounded at the lack of research being conducted on this population. Her examples are as specific as examples in a textbook. If you want realism, ask an actual parent or public special education teacher. As for community, everyone will have a different definition based on personal experiences. If we want to consider ourselves an inclusive society, we have to include everyone. Also, remember that a disability can happen to anyone at any time. How would you want to be treated? What opportunities would you want? Good job, Amy!

Thank you, Amy, for this article. I wholeheartedly concur. My son was fully included in my other two children’s school. This was tremendously successful until his sudden and unintended bouts of aggression, self-injury and property destruction intensified to a degree that he could no longer safely live at home. After many failed “community” placements ended in a two-week jail time, he was placed in a developmental center. At first, I was horrified. Then I got to know many very caring and skilled staff. Was there room for improvement in that setting? Oh yes, but there was also so much opportunity. Whenever my son and I would walk around the campus, people would wave to him and cheerfully greet him by name. He loved that. That is community! The center was closed and my son was moved to a community-based living situation. The house is beautiful, the staff is caring, and yet he is totally isolated. He is certainly isolated from any neighbor contact as well as from peers beyond his two housemates. It is not safe for him to walk by himself to any place in that area nor is that ever offered to him. I tried to convince the Developmental Department of California to re-imagine the amazing acres of the developmental center. Just like in a Camphill or other farm-based program for people with developmental challenges, the Sonoma Developmental Center used to offer meaningful work and leisure to its residents: it once had a farm, bakery, laundry, swimming pool, shoemaker, school, hospital, post office, store, coffeeshop, campground, and much more all on campus – not to mention acres and acres of hiking paths. It was a true village where it was safe for its villagers to roam around freely. This was until budget cuts started shrinking what was offered.

I keep wondering: Why is it okay to build beautiful senior living communities that are designed to specifically serve that population, but not communities for those like our sons with their respective challenges and needs?

The author claims to be an academic but fails to cite any sources. Her argument is thusly weakened. Actually citing sources and giving *specific* examples — not these vague examples that we have no idea are real or represented accurately — would give us some real substance to latch onto. Instead of academic discourse all we have here is a personal essay. And as a scholar of community geographies, I can tell you the author’s argument that “community” is primarily meant in a geographical sense these days is doubtful, and her presentation of this argument is weak at best.

I just want to say that working in the field of IDD in Ohio, that Amy Lutz is pointing out the weaknesses in the system and find her writing spot on and challenging conventional (and many a times unsuccessful) wisdoms.

She is writing in an alumni magazine for Penn, not a scientific article.

I am not sure what a “scholar of community geographies is, but I am sure you are good at it.

What makes Advocates and Bureaucrats think they know more about individuals needs then there Parents, or their Healthcare profession, every person is different you can’t just say you know this will be better for them. For years structure and consistency was what the healthcare professionals were telling us was needed, Now Advocates that have never met with us or have delt with our family are saying they must be integrated by taking away there shelter workshops, because they are not allowed to be with other disabled people. They can’t even get bullying under control in a regular school, how are they going to keep a disabled individual from being mistreated. All because we must be with in the community.