It has history, and it has tradition. Dwight Eisenhower, Desmond Tutu, and Mikhail Gorbachev spoke at its podium; Diana Ross fronted her Supremes on its stage; Dr. Judith Rodin and Dr. Sheldon Hackney were inaugurated there as Penn’s presidents in pageantries worthy of medieval monarchs.

Irvine Auditorium also has the 10,731-pipe Curtis organ, one of the world’s largest musical instruments, and one that has filled the great hall with sonorous blasts on hundreds of occasions.

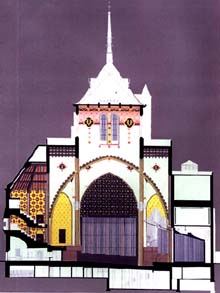

If all goes as planned, the tradition will be preserved and the sonority enhanced. By 1999, the tarpaulins and scaffolding that now clutter the interior will give way to reupholstered seating, a new stage, new heating and ventilation systems, additional performance and practice spaces, and improved acoustics; Irvine’s colorful painted decorations will also be restored. The $23 million restoration and renovation project that got underway in June will, the University hopes, make the auditorium a more effective place for all kinds of performances. The work is part of plans for the Perelman Quadrangle, an academic and activities complex that will serve as a meeting place and common ground for students and student organizations.

The Irvine project has not lacked detractors, however. Some alumni and members of the Curtis Organ Restoration Society, a volunteer group that has overseen the organ’s maintenance and use, had expressed concerns about the potential for damage to the 71-year-old organ during renovations.

Although University officials have addressed those worries with plans to protect the organ, a group calling itself the Irvine Preservation Society continues to charge that the acoustical redesign will impair the organ’s sound and Irvine’s appearance. The group also argues that the creation of three smaller rooms within the building — for a rehearsal studio, café, and recital hall — will “destroy the integrity of Irvine’s remarkable interior by breaking it into a jumble of smaller spaces.”

But Penn officials and the project’s architects, Venturi Scott Brown and Associates, are confident that the acoustics can be upgraded and other changes can be made without destroying the building’s architectural integrity — or the organ’s majestic sound.

One of the challenges, explains Joanne Hanna, G’87, director of development for the Perelman Quadrangle, is that while Irvine’s cross-shaped design creates great resonance for organ music, it causes other sounds to “fly” all over the room rather than be directed to the audience. The project planners hope to address this problem by modifying the shape of the room, removing balconies on both sides of the stage and replacing them with sound reflectors. In addition, acoustical banners that can be raised or lowered will be hung from inside Irvine’s tower, and a shell of acoustical material will be inserted in the new stage.

The Irvine preservation group argues that these changes will be “inappropriate and out of context with the architectural style of the building.” But Hanna says they need not worry: “All you have to do is to look at the other restoration projects we have [on campus], like the Fisher Fine Arts Library … [The architects] bend over backwards to make things as historically accurate as possible and fit into what they would have looked like [when built].” Irvine, whose exterior was inspired by Mont Saint-Michel, was built in 1926; its chief designer, Julian Abele, Ar’02, was the first African-American graduate of Penn’s School of Architecture.

Aesthetics hasn’t been the only concern of some project critics. In one letter posted on the Irvine Preservation Society’s Web site, Michael Rowe, coordinator for the 1998 Organ Historical Society National Convention, wrote that renovations of an auditorium at a Colorado university “sucked” the life out of the historic organ housed there. Change Irvine, he warned, and the same thing could happen.

In a letter sent in August to those who had expressed concerns about the project, Dr. Stanley Chodorow, Penn’s provost, wrote, “The Irvine project aims to preserve the integrity of the organ and the architecture of Irvine, which are certainly among the University’s finest treasures.” On the recommendation of an independent organ consultant, the organ’s pipes have been removed and stored by its original builder, Austin 0rgans in Hartford, Conn. Austin will restore and tune the pipes, renovate the organ’s chambers, and build a new base for the organ console.

“Throughout the design process,” Chodorow wrote, “the architects and their acoustic, mechanical, and construction consultants have been working to obtain optimal acoustical results.” Renovations “will in no way alter the passage of sound from the organ chambers into the hall.”

Above Irvine’s stage, a rehearsal hall will be built, to be named after Emily Sachs, a Penn student and dancer who would have graduated next spring had she not died of asthma her freshman year. There are plans for a two-story recital room seating 100 people on the east side of the building and a two-story café/lobby space on the west side. Both side spaces have been underused, says Hanna, adding that these projects are “truly going to enhance rather than cut up” the building.