Two new books by an architectural historian examine Frank Furness’s exuberantly influential edifices.

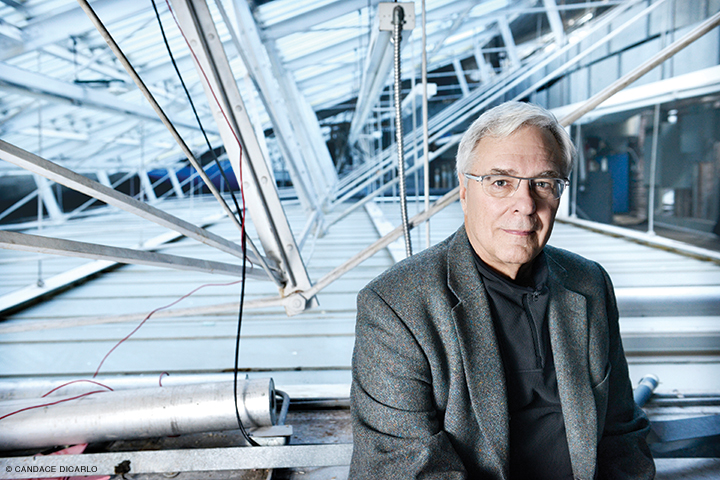

George E. Thomas Gr’75 loves to talk about Philadelphia’s role as the first city to erect a truly modern building in the United States. But the former Penn faculty member isn’t referring to the 1932 International-style PSFS skyscraper, designed by George Howe and William Lescaze. He’s talking about the dazzling, over-the-top Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts by Frank Furness and George Hewitt, which opened on North Broad Street back in 1876, the year the country celebrated its Centennial in Fairmount Park.

Furness, generally regarded as the building’s primary designer, “was working in a city that was the steam equivalent of Silicon Valley—a city where Baldwin Locomotive Works was producing 10 trains a day,” he points out. “And all of Philadelphia’s major civic and cultural institutions, including the Academy, were led by industrialists who were not interested in the past but were forward-looking. So Furness broke boundaries because his clients expected it.”

In First Modern: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, published last fall by the University of Pennsylvania Press, and in the forthcoming Frank Furness: Architecture in the Age of the Great Machines (April 2018, also by the Penn Press), Thomas lays out his case for naming Furness as the key modern architect of the 19th century. He further claims that it was Furness who laid the foundation for modernist structures like the PSFS—not, as common wisdom holds it, the European disciples of Walter Gropius’ Bauhaus movement.

That the Academy’s new home—the third for the museum and art school, which was founded in 1805 by Charles Willson Peale and others—should be put forth as an exemplar of modernism is, to put it mildly, radical. Museumgoers and architecture buffs can easily identify its style: a high Victorian extravaganza of material and color, rife with a mishmash of Venetian Gothic, Moorish, and British Arts and Crafts motifs, exuberantly encrusted with ornament. Arches and pillars, gilding and curlicues—this is not the White City of Tel Aviv, where 4,000 stuccoed and linear apartment buildings and hotels offer the greatest concentration of modernist architecture in the world.

Ahh, but look closer, Thomas exhorts.

“On every surface, exterior and interior, machine-based iconography pervades the Academy fabric,” he writes in First Modern, adding that the decorative details with which Furness furbelowed the Academy’s banisters and lamp posts turn not to nature for their inspiration, as might be expected, but to industry: pistons, ball bearings, and drive shafts. (Next time you ascend the building’s grand staircase, check out the wood railings.) And even when more traditional elements do appear, they are the products of the newest machine tools available, Thomas adds. The striking tour de force of ornament that greets the visitor at the top of the stairs, for example, features little that is hand-crafted: crimson and gold floral plaster florets were cast, leafy patterns on the stone panels were sand-blasted through a rubber stencil, and marble columns were turned on steam-powered lathes and their capitals carved by drills.

Perhaps most significant, suggests Thomas, is the massive iron truss along the Cherry Street façade that both supports the upstairs gallery walls and makes possible a series of skylights that deliver natural light into the ground-floor studios. Instead of relying on the usual load-bearing arches—which would have blocked some of the sunlight—Furness opted for a system more often found in the Philadelphia factories owned by the men who had hired him. And he did so with relish, exposing the bridge-like workings and showcasing them with decorative brick accents. For Thomas, it’s a short leap from here to other, more familiar, talismans of modernism, such as the strip windows of the Bauhaus and the exposed skeleton of the Pompidou Centre (mid-1970s) in Paris.

In his Great Machines, Thomas delves into some other works, looking at a few of the many train stations the architect designed for his railroad clients. He also closely examines another jewel, the Fisher Fine Arts Library, which for years was rumored by Penn students to have been designed as a train station.

Just as the Academy offered a master class in space planning—by fashioning a distinct entry sequence, deftly setting students’ ateliers behind the public entrance, and ensuring natural lighting for both the making of art and the viewing of it—Furness and his team (which included Melvil Dewey, of the eponymous cataloguing system) paid careful attention to the ways in which the Penn library would be used. Its floorplan also directs the visitor through a series of spaces, moving her from the communal porch-like entrance to the privacy of upstairs administrative offices (if desired) or through a pair of leaded glass doors and into the sky-lit library. Behind the scenes, the designers created rows and rows of book stacks within a self-sustaining system of steel columns ingeniously designed to be expanded with additional bays as the collection grew. And, as he did at the Academy, Furness gave prominence to industrial materials like iron and steel, which appear both in the truss work that soars above the reading room and in the ornamentation throughout the building, especially on the distinctive, lacy staircase.

With the back-to-back publication of these two books, Thomas continues a lifetime of work on Furness that dates to research he prepared as a grad student for the catalog of the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s 1973 retrospective on the architect, and which he picked up two decades later with a survey, Frank Furness: The Complete Works (co-authored with Jeffrey A. Cohen C’74 Gr’91 and Michael J. Lewis G’85 Gr’89).

“Hopefully,” says Thomas with a chuckle, “these new titles are my final statement on the guy.”

—JoAnn Greco