The Penn Cultural Heritage Center was launched to provide a forum for an “intellectual discussion” of the meaning of heritage and the role of communities in preservation efforts. Then came the Syrian civil war and the rise of ISIS.

BY JAMIE FISHER | Photography by Candace diCarlo

Sidebar | The Peace Children of Syria by Melissa Croghan

Before the barrel bombs, before the sandbags, before great cities had fallen and a great surge of people had fled, when the vocabulary for what was happening was still uncertain, before the mosaic was saved and the museum was lost, and certainly before the BBC started calling, Salam Al Kuntar came to the Penn Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and gave a talk. The title was “Syrian Cultural Heritage in the Crossfire: Past, Present and Continuity.”

This was a topic Al Kuntar understood intimately. A Syrian herself, she had been working with Syria’s Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums for 15 years, participating in excavations up and down the country.

Before the civil war began, she had been working at the Syrian National Museum in Damascus, preparing to collaborate with the Louvre on a new museum. But Al Kuntar, whose politics had tended towards the oppositional, had recently fled Syria. As the conflict progressed, the project was put on hold, and Al Kuntar began to feel that her work had become impossible. Even before ISIS, she says, the government would not accept any criticism. When she left the country in 2012, she joined the Penn Museum as a postdoctoral fellow.

In her lecture, Al Kuntar described an atmosphere at home that was thick with terror and paranoia. She spoke about the damage inflicted on World Heritage Sites, the looters of the Free Syrian Army, and the “indiscriminate” heavy fire of Assad’s forces. Terrorists, the regime claimed, were using historic sites as rabbit holes.

As Richard Leventhal, the former Williams Director of the Museum who serves as executive director of the Penn Cultural Heritage Center, remembers, Al Kuntar had no sooner finished her talk than she walked over to him and Brian Daniels Gr’12, the center’s director of research and programs.

What are you doing about Syria? she asked.

It was a good question. For the past three years, the PennCHC has been working with growing urgency to answer it.

Established in 2008, the PennCHC was envisioned as “an intellectual discussion of what heritage is, focusing on the construct of communities, how communities should be one of the most important driving forces in the preservation of heritage around the world,” Leventhal explains. By the time Al Kuntar posed her question, it had established several successful model projects in Mexico, but had never attempted to work in an active conflict zone, let alone on the scale of the crisis in Syria. Yet today one of the PennCHC’s signature projects amounts to a kind of cultural crisis unit. The project is called Safeguarding the Heritage of Syria and Iraq, or SHOSI. It is one of the most successful preservation programs in the Middle East today.

It is also remarkably tiny. SHOSI is, for the most part, three people—Al Kuntar (now a visiting assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology), Daniels, and postdoctoral fellow Katharyn Hanson—lightly overseen by Leventhal. Al Kuntar translates and connects the PennCHC to people on the ground in Iraq, Turkey, and Syria; Hanson, a former political staffer on Capitol Hill, has testified before Congress, with studied aplomb, on the importance of placing import restrictions on looted artifacts; the affable and assured Daniels, whose fascination with “ideas about cultural property and the public good” has led him everywhere from protecting underwater treasure troves to working with the Montenegro Ministry of Culture,suggests with unconvincing modesty that all he does is “make sure that all the squeaky wheels get some WD40.”

All three organize workshops and speak to a blur of reporters in print (The New York Times, The New Yorker, and National Geographic) and on the air (NBC, NPR, and the BBC). They work closely with the Smithsonian Institution on preservation initiatives, sweet-talk the donors on whose support the center depends, and cross their fingers at night. Even on the best mornings they wake to fresh depredations visited on the region’s people and cultures, present and past.

In light of its limited size and resources, the extent of SHOSI’s impact was somewhat unanticipated. When speaking about the program’s origins, the team can seem a little stunned, likecoffee-shop guitarists unnerved to find themselves with a stadium anthem. But while Leventhal had originally envisioned something smaller when he founded the center—he points, almost wistfully, to those long-term model projects in Mexico—he has no regrets about the shifted focus. “The process of destruction in Syria and Iraq is immediate,” he says. “It is not going to wait around.”

While the situation in Syria already looked grim by the time Al Kuntar fled the country, there was little indication of how much worse it would get. In her spring 2013 talk, she could still speak with tentative optimism about planning for “the end of the active combat and the start of recovery.” But in subsequent months, the civil war intensified and ISIS began its rampage across Syria and Iraq. If you were to play a tape of the past three years in reverse, you would see what amounts to an archeologist’s fever-dream: Assyrian and Babylonian sites reassembling themselves; the cities of Nimrud, Hatra, Aleppo, Homs, and Palmyra unfolding from the rubble. Rome wasn’t built in a day, but it’s astonishing how much of Mesopotamia’s ancient culture has been lost in the span of months. At UNESCO’s last count, in December of 2014, 290 of Syria’s designated cultural heritage sites had been damaged or entirely destroyed.

The director-general of UNESCO has repeatedly condemnedSyria and Iraq’s dismantling as “war crimes.”

Back in 2012, Al Kuntar was still in contact with many of her colleagues. “I thought, ‘There is a window that we can work to help these people.’”

Initially it was unclear what help would look like.From the beginning, SHOSI has taken direction from communities on the ground in the Middle East. “The PennCHC has a different perspective on heritage,” Al Kuntar says. “These are local people, local professionals, planning what they want to do with their heritage.” No one is being told what they need to save, or what they should value. And UNESCO studies suggest that in times of political unrest, local actors can accomplish what national and even international organizations can’t.

As it turns out, Daniels says, “When you ask, ‘What do you need?’ generally the first answer is training.” SHOSI’s workshops, which focus on emergency preservation and risk management, were long in gestation. The first workshop for Syrian museum professionals was held across the Turkish border, for four days in June of 2014—“It had taken that long to get funding,” Daniels explains—followed by a longer, multi-week workshop in the Iraqi city of Erbil late last summer.

The workshops are held in conditions that seem both dangerous and startlingly normal. Describing the workshop in Turkey, Daniels says, “We were in a conference. In many ways it felt like any other conference. Except for the fact that we were 40 kilometers from the Syrian border.” When I spoke with Hanson in August, she was at the SHOSI workshop in Erbil. She described the city as “a thousand degrees, no people screaming on the streets, like any bustling Middle East city.”

On the other hand, at roughly the same time the year before, Hanson and other participants in a University of Delaware program were being rescued from the same bustling city; ISIS had crossed into the Erbil plain, triggering a barrage of airstrikes. Hanson and her colleagues left on a commercial plane chartered by a professional evacuation company. While she doesn’t downplay the evacuation’s seriousness, she does takes it in stride. “It’s what they do for the oil companies and NGOs and all that,” she says.

As desperate and ad-hoc as protecting artifacts in a conflict zone may seem, there are, in fact, conventions. UNESCO’s International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (known as ICCROM) maintains the accepted standards for emergency preservation, risk management, and disaster response. “First aid for culture, basically,” Daniels explains, in catchy shorthand. These are best practices for a wide range of practical tasks: how to shore up walls, cage stone sculptures, clear invasive vines with sodium arsenate, and so on.

SHOSI consulted with scholars in the US and with ICCROM, but the program, limited by costs and by the wary eyes of customs agents, ultimately worked with the materials they could get across the Turkish border. This is not so different from the constraints that first shaped ICCROM conventions; many of the techniques employed by contemporary first-responders in post-earthquake Nepal and Japan, post-revolutionary Egypt, and Taliban-era Pakistan were first developed in the heated aftermath of World War II, as conservators raced to protect threatened artifacts.

Attendees at SHOSI workshops are given training and supplies, but they are also, crucially, integrated into a response network that allows them to tell their partners what they need. “This is not just outsiders coming in,” Leventhal explains. “We are working directly with communities in Iraq and Syria, working with people on the ground on what they identify as projects. This is not us going in and saying, ‘You must save everything.’”

Outside of workshops, SHOSI’s approach varies according to the communities it works with. In Iraq, the team has the distinct advantage of working with a functioning government. In the Kurdish city of Erbil, the central hub for most of Iraq’s NGOs, SHOSI works closely with the Iraqi Institute for the Conservation of Antiquities and Heritage (IICAH), where Hanson serves as program director for the Archaeological Site Preservation Program. The situation in Syria is more disorienting. Here SHOSI collaborates with local NGOs like Syria’s The Day After Association, and with local volunteers, who tell SHOSI what they intend to protect, and what they need to do it.

“In these moments of conflict and lack of centralized framing,” Leventhal says, “communities are looking for anchors.” Penn provides resources and an organizing framework—the trellis. But the vines were there to begin with.

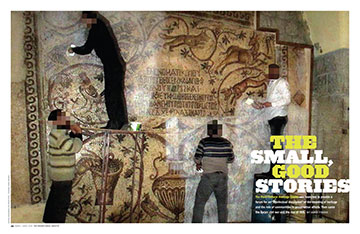

The Ma’arra Mosaic Museum is the most celebrated example of SHOSI’s approach. Once an Ottoman-era roadside inn, the museum is filled with 1,600 square feet of Byzantine and Roman mosaics. The mosaics—robust-looking deer, long-tailed birds, and pink flowers—are cemented firmly in place.

Initial calls for action came from the Ma’arra Museum itself, where Al Kuntar’s colleagues worked. By this time ISIS had put down roots in northern and eastern Iraq and Syria. “Aleppo was a mess,” Daniels says. The museum staff knew that they were going to come under rocket fire. But the mosaics could not be moved.

In late 2014, after securing permission from the local militia that controlled the museum, SHOSI started its emergency preservation project. Curatorial staff and volunteers cleaned the mosaics and applied cloth and the synthetic Tyvek sheeting to bind the tiles. Then they cushioned the mosaics with sandbags to soften blasts and absorb shrapnel. The interventionwas physically as well as politically delicate, since participants needed to avoid attracting the kind of attention that could make the Ma’arra Museum a target. As they moved rolls of Tyvek into the building, volunteers claimed that they were bringing in burial shrouds.

The project was completed by winter; in early summer, the museum took a barrel bomb from Assad’s forces. Severe damage to much of the building was inevitable. Still, the most significant mosaic panels survived intact.

“This is a case where you don’t want to say it worked,” Daniels says. “But it worked.”

“The media tries to end with that story,” Hanson says, “because other stories are more depressing.”

With cases like the Ma’arra Museum, the SHOSI team is often torn. They would like to tell success stories that promote the program and, more importantly, inspire hope. But they also recognize the necessity of presenting an accurate portrait. A complete, hard-nosed look at the situation in Syria and Iraq would include other stories: The video ISIS released showing the destruction of Nimrud, the former Assyrian capital. ISIS militants sledgehammering Assyrian statues at the Mosul Museum, the second largest in Iraq. Assad’s shelling of medieval buildings in Aleppo. Or the nonpartisan looters who have dug thousands of holes in Apamea, Mari, and Dura-Europos, the city once known as “the Pompeii of the Syrian desert.” Most mornings, Daniels wakes up and checks his email to see what has been bombed overnight. The news cycle determines the rhythm of his days.

When talking about journalists, Hanson has a wry sense of humor that can remind you of a teacher with a class that never seems to learn. For all the drama of barrel bombs and terror-sponsored smuggling, the most important crises in the Middle East today are slow moving. Looting isn’t usually carried out by ISIS: In communities suffering from poverty, institutional inequality, and chronic instability, cultural heritage becomes an easy resource to exploit. This process is only accelerated during a crisis.

The media focuses on the looting of antiquities because it is, as Hanson drily puts it, “the sexy crisis”: “They make movies about that stuff, right? Museums being looted.” In contrast, “Nothing says boring quite like lack of infrastructure maintenance. If you want to sell a headline, looting is the way to go.”

And the media itself “is one of the drivers of destruction,” Hanson says. Even the most conscientious journalism can put people and artifacts in danger. Looking at photos of the Ma’arra preparations, you zoom in to correct for low resolution, then realize that someone’s face has been blurred for his own protection. Well-meaning reporters have asked Hanson to help produce maps of threatened artifacts—“like we should give ISIS a map of what’s out there to damage,” she says, her eye-roll nearly audible over the phone. “By reaching out and raising awareness,” Hanson asks, “are we putting more things in jeopardy? By making a big public outcry about things that may not have been a focus before?”

Similarly, SHOSI’s future plans, while not quite jealously guarded, must be spoken about with a certain wariness. More workshops, new projects: documentation, heritage education, and the emergency stabilization of looting-damaged sites in northern Syria. They will work in Iraq and Syria when possible, across the border in Turkey when not. Such circumspection is plainly a challenge for the team, who are used to speaking openly— to be blunt is a favorite phrase of Leventhal’s—and with all the precise attention they turn on artifacts, excavations, and workshops.

Measuring the success of the program is difficult. Leventhal suggests that it lies with “the small, good stories we’re able to tell,” successful interventions like the Ma’arra Museum. Daniels suggests that the real victories are “much more intangible.”

“There’s a sense of hope that someone out in the international community cares about these kinds of issues,” he says. “I think it’s a credit to Penn that we can say we actually do care about this on the human level.”

While dwelling on success stories may present an inaccurate picture, the story suggested by the Ma’arra Museum is undeniably compelling: A mosaic of peoples and cultures, coming together to protect a mosaic that has already survived thousands of years. It is an alluring image of cooperation. It is also, in part, the fulfillment of the PennCHC’s mission statement: In Leventhal’s words, “Communities coming together to preserve heritage.”

This spirit of cooperation extends to Penn’s campus and the wider Penn community. When discussing future plans, Leventhal talks about the intellectual activities on campus. Penn Museum interns and entire classes are participating; undergraduates and graduate students are “pulling together large data sets that will extend on into the future,” documenting the condition of heritage sites in Syria and Iraq. Even among the students and faculty who are involved more tangentially with SHOSI, the PennCHC’s regular lectures have encouraged robust discussion.

And although the team is too modest to say so directly, the real success of SHOSI might be suggested by cooperation: how many institutions are eager to work with the PennCHC, and how many are anxious to start similar programs of their own. SHOSI has support from the J.M. Kaplan Fund, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and Sotheby’s. The Smithsonian is a committed partner in every project SHOSI undertakes. The American School of Oriental Research has begun working with the State Department, mimicking Penn’s program. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has put out calls for action along SHOSI’s lines. These are cultural behemoths. SHOSI is three people.

But if it lacks the funding heft of larger institutions, by staying small SHOSI moves more deftly than they can. It is able to do so partly because each member takes on a fantasticload. Hanson describes Al Kuntar as “busy,” which means something coming from her. I was able to speak to Hanson on three occasions: once in the minutes before she left for dinner in Erbil; once in a taxi on the way to the airport; and once as she ate lunch, searched for her passport, and packed for Istanbul. When you ask the team about their own research over the past few years, they seem bemused. As Daniels explains, SHOSI is not his only project—he flits from coast to coast, continuing his work with the tribes of California’s Klamath River watershed—“but it’s the project that eats 120 percent of my time.”

The immediacy of their work is, in one sense, unconventional. The word archeology can conjure up images of objects fixed in place: a massive obelisk, or colossal Sphinx staring you down. To an outsider, archeological work that focuses so intently on the present can seem atypical.

But it is also true that archeologists are always shaped by their time. Daniels likes to say that people in his field don’t have the luxury of choosing their subject matter. It chooses them. When he was an undergrad, as the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 sent hundreds of thousands of cultural artifacts back to their respective tribes, “if you were a graduate student at that time and had a pulse, you were cataloguing textiles”; a decade later, as Iraq’s museums were being looted, “if you had a pulse, you were pressed into cultural heritage issues on Iraq.” Both crises shaped his professional development. By 2008, his collaboration with the State Department, teaching customs officers how to recognize looted artifacts, had led him to his current work with Leventhal and the Penn Museum.

Hanson returned to graduate school after working for Wisconsin Senator Russ Feingold in Washington. Then the Iraq War began. “In the first news reports,” she recalls, “all these artifacts I had seen in my archeology classes were being stolen. I pretty quickly came up with the idea of returning to graduate school with a public policy angle, doing advocacy work.” A renewed focus on Mesopotamian artifacts brought her naturally to the Penn Museum.

Leventhal himself has been at the forefront of a growing trend in anthropological archeology, one that encourages researchers “to think not just about the past, but how the past is used in the present.” This was one of his goals in establishing the PennCHC. Syria has put this philosophy to an extreme test.

“I think this is not what your typical Mesopotamian archeologist does,” Hanson says. “But I figure if I love old things, I might as well do something useful with it.”

“Our approach is different because we focus on people,” Al Kuntar says, and humanitarian concerns weigh heavily on the SHOSI team’s collective heart. By the UN’s conservative estimate, over 220,000 Syrians have died since the start of the civil war, and 12 million Syrian refugees have fled their homes. At a time of acute suffering, all members of the team are aware that, as Hanson puts it, “Stuff is not people.” This point was occasionally brought home during workshops. “The conflict was never far from anyone’s mind,” Daniels says. “During one lecture, a participant got a text message that his hometown had been barrel-bombed. Everything stopped for 20 minutes while we figured out whether his wife and kids were alive.”

But at certain times the line between person and object becomes increasingly fine. Partially this is a matter of vocabulary. Emergency preservation is first aid for culture. Particularly vulnerable objects may be evacuated. The final stage is recovery and rehabilitation. When Hanson talks about a beloved artifact in the Penn Museum’s collection, she calls it “this guy.” “He’s not on display,” she says, “but he’s fantastic.” And when ISIS released a video of Nimrud’s destruction, Hanson recalls, her colleagues tried to take the site down—a gesture of decency and respect that seems terribly analogous to blocking ISIS’s beheading videos.

It can also be misleading to imply that there is truly a choice between saving people and saving objects. As Al Kuntar noted in her 2013 talk, “While the destruction of the ancient past may seem insignificant compared with present-day atrocities, the irrecoverable damage to cultural heritage might have a severe impact on the cultural identity of the Syrians who survive this war. … [T]he damage to the Syrian cultural heritage is not merely the loss of magnificent historical monuments but rather an acute disruption of a dynamic past with its living historical places and traditions.” Although Al Kuntar left Syria three years ago, many of SHOSI’s regional volunteers are personal friends who have elected to stay. Several have died. A documentarian was killed recording the violence in Aleppo. Another colleague, Khalid al-Asaad, the archeologist affectionately known as “Mr. Palmyra,” was decapitated by ISIS last summer. Militants suspended his body by the wrists from a traffic light, along with a signboard identifying him as an “apostate.” He was 83, and left behind several children, including a daughter named for an early Palmyrian queen.

Al Kuntar hesitates to suggest that professionals like al-Asaad stay only to protect Syria’s artifacts; largely they stay because they have no other choice, if they want to keep their families together. But for those who have stayed, Al Kuntar says, working may help “establish some kind of normality,” she says. “It gives them hope, and empowers them to survive difficult circumstances.”

The same can be said of Al Kuntar herself. Hanson, who met Al Kuntar on a Syrian excavation nearly a decade ago, describes her as “brave and fierce,” someone who “has really channeled her sense of anger and frustration at Syria into a form of action.” Al Kuntar is soft-spoken, but at times you can hear a thin wire of anger underneath her words. When the SHOSI team feels exhaustion and despair, Hanson says, “She really calls us out on that. Less talk and more do.” As the crisis worsens, Hanson and her colleagues have found themselves struggling to find “an optimistic framework” for addressing its challenges. It is easy, she says, to “bemoan the fact that it’s happening and that it’s a crisis.” It is harder to do something about it.

Daniels suggests that cultural heritage reminds people who they are, gives them pride and a sense of fixedness in the landscape they occupy. “It’s been so easy for people to say that there are human concerns over there and cultural heritage concerns over here,” he says. “And I get that.” But he adds, drawing an analogy with the genocides of the last century, “It’s not just about trying to remove the people. It’s about trying to erase their presence. To erase that existence, so that they have nothing to come back to. As cultural heritage professionals, we understand that they’re trying to erase their identity. We’re trying to give them something to come back to.”

Jamie Fisher C’14 is a freelance writer and translator.

The Peace Children of Syria

Art can’t provide a way out of tragedy, but perhaps a way through.

By Melissa Croghan | Last May I went to Jordan to lead art and poetry workshops for the children of refugees from Syria and Iraq who have flooded the country. I created illustrations for coloring books, designed poetry exercises, and donated art supplies. I taught 200 children, and was able to sit down and spend time with nearly every one of them.

It was a photograph I’d seen in December 2013 of displaced children at the Jordanian border that compelled me to help them. Though their eyes showed worry and sadness, their faces were cheerful, and every one of them had their hand raised in a peace sign. Despite all they had lost, these were hopeful hands. I thought of them as The Peace Children.

My daughter was a diplomat at the US Embassy in Jordan’s capital, Amman, and I reasoned that I could live with her while teaching my workshops. A contact in Jordan connected me with Caritas, a respected global humanitarian organization. Jittery but determined, I flew from JFK to Queen Alia Airport on May 3, 2015.

Caritas provided me with a car and driver, as well as a translator named Waed. I had a new site in Jordan to go to every day. On my first day teaching I met Tarek. The largest boy in the class, he had a serious countenance but wore a cheerful pink shirt. He liked to draw right off the bat, especially enjoying our inventive animal exercise. His jowly creature with wide eyes that could see all the way home to Syria drew the admiration of other students. If I had to pick one student who was benefiting from my workshop, then surely it had to be Tarek. He had dropped out of school after being bullied mercilessly for being Syrian, but despite these hardships he was keen on learning drawing techniques from me. But a half hour before the workshop ended, he abruptly rushed out of the classroom. I worried that maybe I hadn’t been a good teacher, after all—that I’d done something to chase him off.

At day’s end I climbed into the car with Waed. As we passed a nearby medical center, I recognized a familiar pink shirt. A large boy stepped out of the building’s double doors. He was pushing a wheelchair, the woman in it greatly fatigued. My window was open and I called out, “Tarek, how are you?” He beamed and shouted ‘Alhamdulillah,’ that all-purpose expression that covers everything from ‘Praise God’ to ‘Everything is good.’ Only later would I discover that Tarek left my workshop early to care for his crippled mother. People whispered that her legs were blown off in an explosion set off by ISIS.

By dinner time at my daughter’s apartment that first day, I felt let down. I wasn’t donating food or shelter to the refugees. I had no solutions to their ongoing tragedy—their homes and cultural heritage in Syria disappearing, destroyed. What audacity to think I could help! In bed late at night, I listened to the call of prayer from a nearby mosque. The music was haunting. Falling asleep, I saw Tarek’s stark eyes. And then I remembered that somber though he was, this boy had taken real pleasure in learning how to pool colors and paint a river that flowed from sky to ground.

Over the next week, each intense day raised different challenges. At the Fuheis-Latin School, set among gently undulating hills, I had between 50 and 60 refugees spread out over several classrooms. I spent my time running down long cement halls from one lot of eager kids to another. The following day I arrived at the Marj Al Hamam Melkite Church only to discover that the children did not speak Arabic, only Kurdish. Waed, who spoke Arabic and English, was upset that she would not be able to tell me what these refugees were saying.

Thankfully, hand gestures go a long way. These children missed their verdant homeland—so different from the Jordan desert—and they spent their time joyfully painting green fields and mountains.

The only place that caused me fear was Zarqa, a city some distance from Amman that also happens to be the birthplace of the founder of ISIS.

The first time we traveled there, Waed remarked in the car, “You write down everything.” True, I was scribbling away in my black notebook as sweat poured down my back. It was 102 degrees, we had no air conditioning, and we were chugging into Zarqa’s pollution-ridden, dusty downtown.

Of course I was writing, I wanted to say. How else does one cope with fear turning the blood in your veins to a slug crawl? My son-in-law had warned me the night before to keep my eyes sharp in Zarqa, even while riding in the car.

The car radiator was having problems, and we stopped at a gas station. All around us were women in black—no full faces in cheerful hijabs as in Amman. Only eyes: wary, and looking at us. But nothing happened. All was calm in my workshops.

Many of my days brought news of further destruction in the region. When working with the Iraqi children from Mosul, it was distressing to realize that their city had lost its art museum during a takeover by ISIS. The fall of the strategic Iraqi city of Ramadi brought a hush to my colleagues at Caritas. Days later, on May 19, when Palmyra in Syria was seized by the Islamic State, there was great fear among my colleagues, and all of us held our breath hoping that the historic temples of Palmyra would be left intact. (As the world now knows, our hopes were in vain.)

It was a small way to combat these horrors, but what I could offer the refugees was the gift of art, the chance to create new culture for themselves. It will be centuries before the handiwork of the most talented artists in the Middle East will qualify as heritage art, but it must start somewhere. And besides, what else is there to do when there are no jobs, and the future looks tenuous at best; what better way to survive?

I was glad to be there with paper, markers, and colored pencils to teach each day, one child at a time. No lofty goal of offering the refugee a way out of his tragedy, but perhaps with the passion of art, a way through.

Melissa Croghan G’89 Gr’92 is a writer and artist and has taught art and poetry workshops to urban children and people of all ages living in poverty.