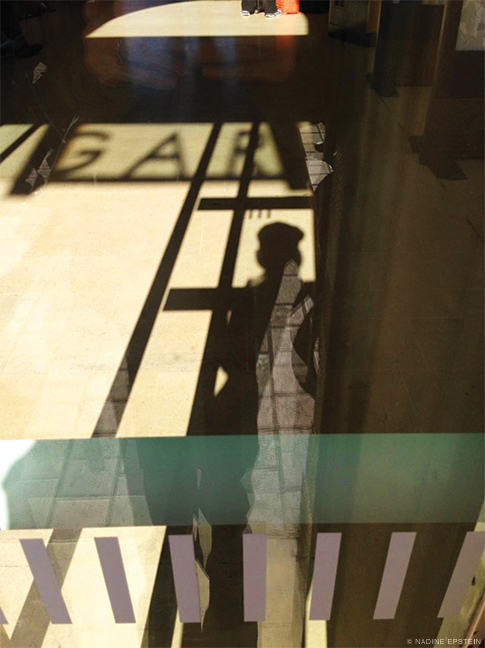

Nadine Epstein C’78 G’78 was walking along a street in Kiev when she first noticed her shadow walking beside her, its outline sharp enough for her to make out the contours of her clothing.

It was the fall of 2008, and she was on her way to interview a former political dissident for a story. Epstein, the editor and publisher of Moment, a magazine of Jewish culture and life [“Living in the Moment,” Sep|Oct 2005], had dreamed of this trip since childhood. All four of her grandparents had lived in the lands that now comprise Ukraine, and she wanted to see for herself the streets and rural pathways on which they walked.

Kiev in 2008 was a “happening, flourishing city” that had only recently emerged from the Dark Ages of Soviet rule, she says in an interview. “Suddenly it was just very hip, and all the dissidents could talk to everyone, and they were famous and sought after.”

But the darker undercurrents had not disappeared. One of the stories she was investigating for Moment (whose editorial staff includes Sarah Breger C’07 and Mary Hadar CW’65) concerned a since-shuttered Ukrainian university whose worldview can be discerned from having awarded a PhD to David Duke for his dissertation, “Zionism as a form of Ethnic Supremacism.”

As she hurried toward her meeting with the dissident, Epstein found herself “overwhelmed” with thoughts of her ancestors, “who had fleetingly called this land home,” as she put it in an artist’s statement. “It was a few-centuries-stop on the 5,000-year trajectory of Jewish wandering.” She pulled out her new iPhone and began to capture images of her body blocking the afternoon sunlight.

A few days later, on Rosh Hashanah, she visited the town of Uman to observe the pilgrimage of Hasidic Jews to the burial place of the mystic Rebbe Nachman. Women, though not forbidden, weren’t exactly welcomed with open arms.

“I spent Rosh Hashanah in this town, and while I was there I had to sort of escape,” she says. “It was all filled with Hasidic men, and so I went to this beautiful park, Sofiyivsky Park, and that’s where I took the photo with the leaves inside my shadow that’s called ‘Uman.’”

“I vanished into what I can only describe as my first iShadow trance,” she wrote. “That was the day I learned that time stops when I shoot shadows: I can continue for hours because there are infinite permutations—that is, until the sun goes down. And even then, there is lamplight, streetlight, starlight, and moonlight.”

Epstein’s iShadow images were recently displayed in New York in an exhibition titled In a Woman’s Shadow at the Jules Backman Gallery in the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion Museum. On September 10, another iShadow exhibition opens at the AG Gallery in Washington.

“This is a project that I just love,” she says. “There’s a lot of mythology about shadows, and I’ve started thinking about their long history in religion and philosophy and literature and astronomy and painting.

“It’s also a very feminist project. I’ve spent a lot of my life finding my voice. I came from a particular world where I grew up feeling almost voiceless. Part of the trajectory of my life in this era as a woman has been to find it.”

Sometimes, Epstein adds, she will photograph somebody else’s shadow. “But finding my own shadow has been a way of marking myself on the places that I’ve been, and on the Earth.” —SH