At the turn of the last century, the CA pioneered the idea of service at Penn with settlement houses and summer camps, and has since been at the forefront of anti-war protests and movements for civil, women’s, and LGBT rights. In the 21st, it’s still providing a “safe space” for students and making a difference on campus and beyond.

BY DAVE ZEITLIN

Photographs courtesy of Christian Association and University Archives and Records Center

Under an elevated train track, in a park struggling to shed its reputation as a drug haven, a group of 50 or so people gathered beside a blossoming cherry tree swaying in the wind.

If you were passing through McPherson Square in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood that late April afternoon, you might have wondered what could have brought them to this rough part of the city. They seemed to have little in common. Within the semicircle formed around a makeshift podium, a man in priest’s garments stood beside someone wearing a Brian Dawkins Eagles jersey. There was a woman gently rocking a baby in a stroller next to a hipster in jean shorts. One man in a suit and another wearing a Harley Davidson shirt stood a few feet from an employee of the nearby El Bar (who pointed out what used to be the “heroin bench” and the “coke bench” in what had been dubbed “Needle Park.”)

Only by moving closer to these men and women of all ages, races, and backgrounds … straining to hear over the screech and rumble of the El train passing … and seeing the four T-shirts stretched on spikes dug into the grass, was it possible to determine why they had gathered. On two of the T-shirts were written names, ages, and dates. The other two had the words Unnamed Male and Unnamed Female.

The shirts memorialized the victims of a recent quadruple shooting in Kensington, and faith organizations from around the city stood beside local mourners to pray for the victims of these tragedies and call for action against “straw sales” by local gun dealers. “It’s blood money,” boomed Bryan Miller, the executive director of Heeding God’s Call, the faith-based gun-violence-prevention movement that organized the rally and press conference. “It shouldn’t happen. And we want to get it changed.”

Also among those gathered, listening intently, were Rob Gurnee, executive director of the Christian Association at the University of Pennsylvania, and Megan LeCluyse, the campus minister of that venerable institution, which for decades occupied the building at 36th and Locust Walk that now houses the Arts, Research, and Culture House (ARCH) and since 1999 has been headquartered at 37th and Sansom streets.

It might seem like an odd place for the CA to be represented, even among such an eclectic mix of people. Kensington is a long way from Penn’s campus, in every sense, and the rally had no direct ties to the University. But the Christian Association—which will celebrate its 125th anniversary this fall as the oldest active ecumenical campus ministry in the United States —has always spread its wings well beyond Penn, especially in impoverished neighborhoods. In fact, for much of the last century and into this one, the organization has been a beacon of social justice and a champion of progressive causes in West Philadelphia and around the city and even, for a time, internationally.

Gurnee, who gives off something of a laid-back Billy Bob Thornton vibe, got his undergraduate degree in political science and a law degree from Emory University, and worked for a number of years in banking and finance. He says he always had a complicated relationship with his faith, believing at first that religion meant “a judgmental God.” But after realizing he was always “the guy sticking up for the consumer and the hourly workers in our company,” he became more conscious of what he wanted to do with his life. He switched gears to run an interfaith coalition before landing his current job with the CA six years ago.

The day before the rally, sitting on a comfy couch at the CA, Gurnee talked about how important the issue of gun violence is in the city and nationally. “It’s the most basic of all commandments, right? ‘Thou Shalt Not Kill’?” he said. “I just feel that God calls us to love one another, and guns are a significant thing that gets in the way of that.”

The Christian Association made sure this message got across loud and clear last December when it displayed on its lawn 200 T-shirts representing Philadelphians killed by gun violence in the previous year. Also featured prominently outside its building—which lies in the same historic complex that houses the Tabernacle Church and the Iron Gate Theater—is a Black Lives Matter poster, an LGBT flag, and a sign that touts the CA as “a public voice for progressive Christianity.”

To the average passerby it may seem jarring for such forward-looking messages to be displayed outside a national historic landmark building. But in many ways, it’s also the perfect snapshot of the Christian Association, which has always kept one eye on its rich history and the other on creating a better future.

Settlement Houses, Medical Missions, and Summer Camps

Around the turn of the 20th century, Josiah C. McCracken M1901 took a stroll past Franklin Field, where he starred on Penn’s football and track teams, and kept going east on South Street. He did not like what he saw. Across the Schuylkill River, just beyond Penn’s campus but seemingly a world away, was a gritty neighborhood filled with needy boys and girls. So he decided to do something about it.

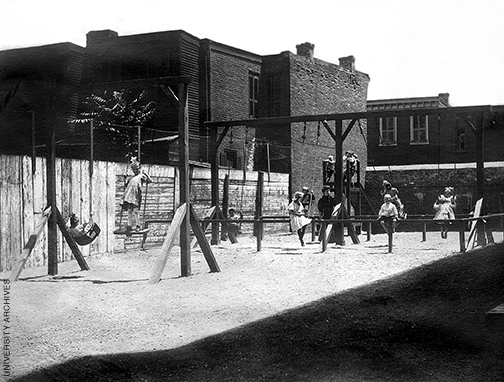

McCracken, who served as president of the Christian Association for three years, began by starting a Sunday school for those kids. Before long, he became one of the first Penn students to set up and volunteer his time at CA-run settlement houses, whose purpose was to provide facilities and mentorship to children, develop what organizers called a “good neighborhood feeling” toward all ethnic groups, and offer opportunities for Penn students to share in “Christian service.”

The CA opened its first settlement house at 2524 South Street in 1899; in early 1907, it opened another at 2601 Lombard Street in a building it purchased for more than $50,000. It was a noble effort and one that remained a crucial part of the CA’s mission for several decades. But remarkably, the settlement house idea was not all McCracken had in mind.

According to University Archives and Records Center director Mark Frazier Lloyd, McCracken was a devout believer who “saw his medical training as a God-given opportunity to help people who did not have modern medical care.” McCracken didn’t just bring his expertise in medicine across a river; he brought it across an ocean too.

In 1905, the CA board hatched an ambitious plan to send McCracken to China to study the feasibility of taking over the medical school from what was then called Canton College. In his book Seeds from the West: St. John’s Medical School, Shanghai, 1880-1952, author Kaiyi Chen notes that McCracken spent seven months in China and “concluded that with the support from the home base, he ‘could do far more in China than he could ever do at home.’” So in 1907, McCracken returned to China to operate the medical school in Canton, which was renamed the University Medical School.

McCracken was “the person who really started to put credibility behind the idea of the Christian Association,” says Lloyd. “The establishment of a China missionary medical school wowed everybody. That was amazing. And he was greatly admired and respected.”

McCracken remained in China up until the 1950s, spending most of his career training Chinese doctors and helping thousands of sick people by improving the region’s medical care. He served as the University Medical School’s president until 1913, then became dean of St. John’s University’s medical school until the invading Japanese deported him and his family in 1942. He came back to China in 1946 and resumed his post for another year before retiring, leaving the country for good only when the school was taken over by the Communist government in 1952.

His mission also set the stage for the CA to become involved in other international causes, which included providing financial aid to Dr. Victor Rambo, a medical missionary who dedicated his life to eliminating blindness in India through eye surgery. And back in Philadelphia, the CA is “widely credited with providing the first hospitality to international students,” Gurnee says, purchasing a building on Spruce Street in 1918 to serve as the home for the International Student House. Although the International House separated from the Christian Association 25 years later, the CA continued its focus on helping Penn’s international community, and since 1997 has run a weekly program called Slanguage in which American slang, culture, and justice issues are taught to foreign students.

Meanwhile, the settlement program—in which everything from religion to athletics to arithmetic was taught by a large team of volunteers—continued to expand, with several more houses opening in South Philadelphia before 1950. It also spawned another exciting venture for the CA, which purchased land in Montgomery County and opened a summer camp for many of those same neighborhood boys (and later girls) who came from modest means. The opening of Green Lane Camp was proclaimed with much fanfare in a 1911 Daily Pennsylvanian article: “June 26. Don’t forget the date, for that is the day when the University Settlement, whose headquarters are at Twenty-sixth and Lombard Streets, will open up for the summer the most wonderful camp that ever delighted the heart of a city kid.” And the city kids from the Philly slums ate it up, playing sports and swimming and running carefree around 70 acres of tree-shaded country land.

“The Christian Association, from McCracken to 1960, was the beacon,” Lloyd says. “It was the voice on campus that was saying, ‘We have a responsibility to inner-city youth. We have a responsibility to alcoholics and other addicts. We have a responsibility to help people across the world have better medical care.’ If you were 19 or 20 and at Penn as an undergrad, or 23 and here as a professional student, and you cared about a bigger world than just the pursuit of a degree, the Christian Association was the place to go.”

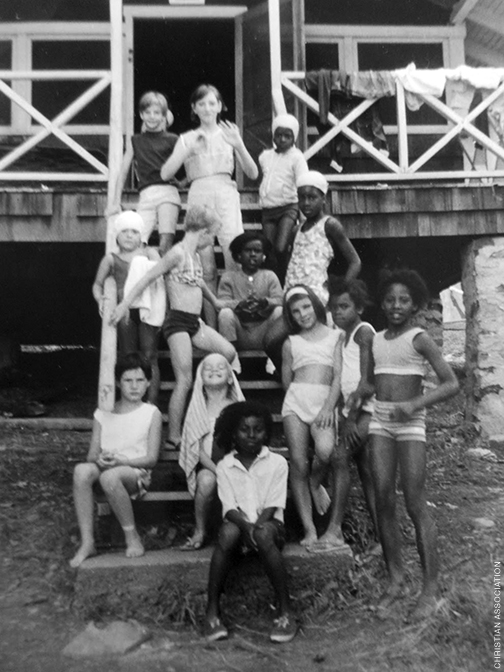

Aaron Bocage C’70 SW’75 was certainly one of those students who got into the CA because he “cared about a bigger world.” But Bocage, who has remained heavily involved with the CA in the four decades since graduating, quickly learned that helping others is also what helped him grow into the person he is today. After Penn, Bocage went on to create youth entrepreneurship programs and is the co-founder and president of the Education Training & Enterprise Center (EDTEC). He regards working as a counselor at Green Lane as one of the best experiences of his life. “The camp,” he says wistfully, “had as much of an impact on us as we had on the kids.”

He has vivid memories from those summer days. One is hearing a prominent alumni supporter use the phrase “an unbroken chain of strong men working to serve poor kids” to galvanize the counselors at orientation. He remembers the pow-wows and the campfire songs and the “frog pond.” He remembers how the cabins were racially integrated even though many of the children came from segregated neighborhoods. And, of course, he remembers the day he woke up early to cut grass with a young woman named Tessa … who would later become his wife. It’s a testament to the camaraderie of the group that he would not be the first or last to meet his spouse because of the CA. While there’s no way to calculate exactly, Bocage counts seven marriages among camp staffers coming out of the four years he was there—a “pretty high rate,” he says, “considering there were only about 30 staff per summer and probably half came back for two or more years.”

“Something happened there,” says Bocage, who recently received a Facebook message out of the blue from one of his “awkward, very shy” campers who just wanted to thank him. “Otherwise, it wouldn’t have had folks from all walks of life still trying to reach back and hold onto it 50 years later. I was lucky enough to be a part of it.”

Activism in the Catacombs

While the summers may have been serene for Bocage, the school year was considerably more chaotic—but in a good way. It was the late 1960s, the country was on fire, and during his junior year Bocage lived in the CA’s former home at 36th and Locust Walk. Literally. His only responsibility in exchange for the free accommodations? He had to chase out all of the activist groups that met in the building so he could lock up around 10 or 11 p.m. It was easier said than done.

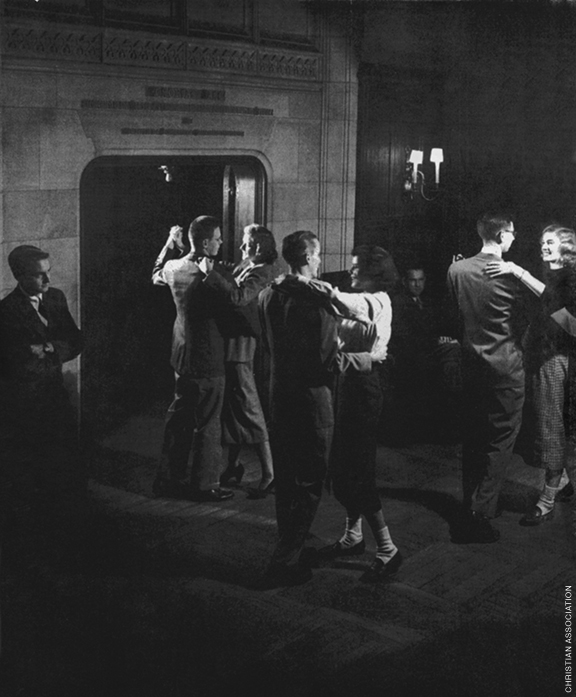

“All the campus protests, the anti-war movement—the CA was at the center of all of this stuff,” Bocage recalls. “So much of the stuff was organized there. So many student groups met there. The catacombs in the basement was the coffee-house for folk music, food, political groups, debates.”

By then, the CA’s settlement projects and camps were beginning to slow down. They had flourished under the leadership of the revered Dana G. How, CA director from 1928 to 1958. In a 1940s-era pamphlet, How called for people to “join with us through your gifts in the happy privilege of lifting hundreds out of their hardships and unhappiness and of actually setting them on the road to a new and better world.” But as time passed and conditions changed the CA had to shrink its reach and sell its camps.

That in turn led to a new era for the CA, which would focus much of its energy on fighting for the rights of African Americans, women, and the LGBT community. “I think what the CA did with the activism in the ’60s was kind of consistent with what it had been doing the half-century before that,” Lloyd says. And it all happened right from the center of Penn’s campus.

Bocage didn’t know much about the CA when he arrived at Penn as a freshman from New Orleans. And he never really thought the basement of a Christian organization would become the hub of anti-war activism and heated political conversations for students like him, determined to avoid service in Vietnam at all costs. (Bocage says that if he had been called, he planned to go to Canada, even though it “wasn’t a real popular decision with my parents.”)

He probably wasn’t alone in his surprise: the building certainly didn’t look like a counter-cultural haven. For its first 30-plus years, the CA had mostly held its meetings out of an office in Houston Hall, so when the organization commissioned its own building in the 1920s, the primary concern was to create a permanent home—accent on permanent. The CA’s board at the time decided to spare no expense, creating a grandiose structure with marble floors, wood paneling, an auditorium, and several expansive dining rooms, offices, and lounges. Over time, while those amenities became somewhat the worse for wear, the basement, or “catacombs,” as it was called, took on a life of its own, becoming a place where people came for the co-ed dances, the whole-wheat pizza—and so much more.

If that “building could talk [it] would tell the stories of being the only neutral and safe space that was off limits from uptight white administrators in the turbulent 1960s where African-American students could audaciously organize a Black Student League and where anti-war protestors could organize against the Vietnam War,” former CA director Beverly Dale wrote in an impassioned letter blasting the Gazette two years ago. (We had suggested, in an article about the ARCH, that alumni were most likely to remember the CA for that whole-wheat pizza or “a meal at the Gold Standard or Palladium restaurants.” —Ed.)

Dale’s letter went on to highlight movie-and-spiritual-discussion nights in the 1980s, talks by “key liberation theologians” in the 1990s, support for the burgeoning women’s movement from feminist clergy, and the “astonishing conversations” that took place among straight Evangelical Christians and gay and lesbian Christians about their “common and yet different spiritual and sexual journeys” even as the Culture Wars raged beyond the CA’s walls. She concluded: “The building at 36th and Locust stands a symbol of what happens when people of faith open their hearts and their intellect to consider the age-old questions of meaning, purpose, and then seek to learn to work together to build a better world.”

Dale served as the CA’s director from 1989 until 2010, overseeing its 100th anniversary in 1991 and the protracted and often tense negotiations to sell its building to the University in 1999. She was not only a female campus minister at a time when there weren’t many but also an enlightened voice for homosexuality and sex education, organizing programming and conversations for such issues around campus.

Even though she movingly eulogized the CA’s Locust Walk home in her Gazette letter, Dale insists that selling it was absolutely necessary to grow the nonprofit organization’s progressive vision and get out from under the huge amount of debt the CA had carried since the 1920s. “I’m proud I got rid of that building,” she says today. “There was no sufficient endowment to take care of the building and do ministry. My fear was the alumni would be really upset and I’d go down in history as the woman who torpedoed the Christian Association. But my hope was to get rid of the boondoggle and free up funds to do some good stuff.”

The negotiations turned out to be more difficult than she anticipated—“just headaches upon headaches,” she says. But the CA was eventually able to iron out the details of the “multi-million-dollar sale” in 1999, which also included as part of the agreement a free 25-year lease on their current space.

Naturally some alumni remain nostalgic when it comes to their old home, which they considered the “original safe space” on campus, since the CA has never been officially affiliated with the University. And even some current students regret the group is no longer so centrally located. But if the old building on Locust Walk no longer houses the CA, its spirit lives on.

A Safe Space for Everybody

As students took their seats for the Christian Association’s final prayer service of the 2015-16 school year, a vital philosophical question was posed: “Whatever happened to Fergie?” someone pondered as Catalina Mullis C’16 passionately sang “Big Girls Don’t Cry.”

OK, so maybe there are more pressing issues than the whereabouts of certain pop stars who may have slipped off the cultural radar. But that moment was probably a representative one for the students who today call the CA home—and come often to lounge around, sing, play games, devour the free meals that are provided every Wednesday, and, most of all, just be themselves. “My favorite part of the CA is just this building,” said Mullis, who majored in theatre arts with a minor in Hispanic studies, shortly before belting out her favorite Fergie song. “We have a meditation room upstairs, which is so calming and comforting. Food is in abundance here. You just have a feeling like this is a home away from home. Everyone here is very nice and so supportive. We love to play Catch Phrase here. It’s just a place we like to come to de-stress.”

For all of those reasons and more, Mullis traded some silliness for tears at this particular late-April service as campus minister Megan LeCluyse offered prayer and advice to the seniors who were about to graduate from Penn. “As you go out, you will need strength and you will need faith and you will need love,” LeCluyse told them during their senior sendoff ceremony. “We hope that at the CA, you have found these things.” Then, with a piano playing in the background, she handed out something more permanent for them to take with them on their journey into adulthood: rocks inscribed with inspirational words.

Upon receiving hers, Mullis hugged LeCluyse and Gurnee for a long time, and then shared an embrace with another senior, Scott R. Gautsche Sprunger C’16. “It kind of just hit me that it’s over,” Sprunger, a philosophy major, said softly when the service had concluded. Then he cradled his new rock in his hand. “I picked one with the word ‘Love’ on it.”

Sprunger “probably spends more waking hours here than I do at home.” But when he first got to Penn, he had “no interest in participating in a Christian group”—he didn’t think he would “have a place in it” because he was gay. He wasn’t even sure if he believed in God anymore despite going to church throughout his childhood. Trying to balance his sexuality with his religion was an “exhausting” internal battle he was ready to leave behind.

But during his junior year, he discovered the Queer Christian Fellowship (QCF), which runs under the umbrella of the CA. From there, he learned of the CA’s remarkable history and how, to his surprise, it pioneered peer counseling for gay students in the 1970s, even before what is now Penn’s LGBT Center got its start in 1982. And then he met Gurnee and LeCluyse, who immediately welcomed him and encouraged him to embrace his sexuality rather than try to hide it.

“It’s just not a priority in the Bible, and things like God’s love are,” LeCluyse says of her views on homosexuality. “If a student is questioning their sexuality, [my approach is] just reassuring them that God loves them, that I don’t think they were created the wrong way, that I think being gay and being Christian is totally doable. And it’s just helping them maybe reinterpret those passages that are used against it, or understanding them in a different way.”

Empowered by his new minister’s message, Sprunger became recommitted to Christianity—so much so that he made plans to pursue a master’s of divinity. “At the CA, to be openly gay, unlike other churches I’ve been a part of, is I have a sense I can fully be myself here,” he says. “I have a much deeper confidence about myself, where I feel like my self-worth isn’t determined by what certain Christians would say about me—which has been an excellent gift the Christian Association has given to me.

“As much as I have trouble with it, [Christianity] has informed so much of my sense of morality and the extent to which I care about justice,” he adds. “I want the church to be better than it has been historically. And I think I can do some small thing to make that the case. So that’s what I’m going to do.”

Sprunger says he will miss the CA’s diversity, which is the “number one thing I noticed” and what “really drew me in.” At the final senior sendoff, there were students of all genders, gay and straight, whites, African Americans, Indian Americans, and Asians. Many stayed long after their final service ended to share memories of the CA, explain their own interpretations of Christianity, and enjoy some craft beer.

“I’ve never been in a space like this where I can be different than everyone else and that’s perfectly OK,” says Josh Butler W’16, who is black and, like Mullis, calls the CA his “home away from home” over the last four years. “I think the people aspect is something a lot of Christian organizations overlook. We have to draw people in, not push God on people. We have to give everyone an opportunity to explore their own faith.”

University Chaplain Charles L “Chaz” Howard C’00, who was a member of the CA as an undergraduate, sums it up best: “Martin Luther King used to say that Sunday mornings are the most segregated hours of the week, referencing how churches tend to separate based on race and class and politics,” he says. “The CA really pushes back on that.”

Then and Now

Growing up in Phoenix, Megan LeCluyse says, she knew “very little that’s 125 years old.” So when the opportunity arose to be the campus minister of the CA after she had come East to attend Princeton Theological Seminary, she jumped at it, hoping not only to honor the organization’s history but to add to it. “One of the things that excited me about the CA was that it was this place that had this rich, deep history,” she says, “and yet it was also in a season of kind of starting over.”

The CA certainly was at a crossroads when Gurnee was hired in 2010 and LeCluyse two years later. There was some controversy over Dale’s exit—she claims she was ousted as a result of “political shenanigans”—but the CA had also been struggling with declining membership and fewer alumni and church donations ever since the heyday of its activist leadership. As Mark Lloyd puts it, “the ’60s kind of flamed out, and the CA flamed out,” at least compared to its pinnacle. Dale claims that when she arrived in 1989, the organization “had been in flux with a changeover of a couple of leaders, but it was in the context of denominational Christianity disintegrating.”

And times—and the campus culture—had changed. In the first half of the 20th century, if you were “the big man on campus and Christian, you were heavily involved in the CA,” Dale says. (Josiah McCracken, for example, the CA stalwart and sports star, was also president of his class all through his student days, as well as president of the Houston Club and associate editor of the school paper, then just The Pennsylvanian.) Since then, the CA has been increasingly in competition with other religious groups established over the years. Currently, LeCluyse says, there are 31 Christian church-based groups and student organizations operating on campus.

Gurnee and LeCluyse say they have tackled the rebuilding challenge by stressing community, establishing a stable student board, scheduling dinners weekly rather than every two weeks, and adding a worship service afterward. LeCluyse jokes that the free meals “tends to be the selling point,” but adds that students find the CA in all sorts of ways—brought along by a friend, visiting the organization’s website (upennca.org), or simply walking past the building and wondering what’s inside. Recently, a student knocked on the door, distressed because at the last Christian group she was part of, her friends told her that she needed to “stop asking questions and just believe.” A few days later, she and LeCluyse sat down for an hour and a half, the questions about her faith flying in from all angles.

“What’s really important [about] the CA is that we’re not going to tell you what to believe, whereas there are definitely parts of Christianity that will tell you, ‘This is what you have to believe if you’re Christian and this is what you’re supposed to do,’” LeCluyse says. “We really do want a space where anyone is welcome. And we do want to be a space where people can disagree and have different opinions.”

“These days, I say Millennials are post-denominational,” Gurnee adds. “They just want to know, ‘How is God relevant in my life?’ and ‘Can I come to a place that’s safe and ask a bunch of questions and not be judged?’ And that’s what we do.”

Gurnee and LeCluyse know that neither their views on Christianity nor the CA’s mission of promoting cultural diversity and interfaith education will appeal to everyone. In the past, LeCluyse says she has noticed people walk away when they see a rainbow QCF sticker on the CA’s table during activities fairs on Locust Walk. And Melanie Young C’15 GEd’16 recalls sitting in a CA office not long ago when someone angrily called in to demand they take down their Black Lives Matter sign, saying hateful things about the movement. The CA “didn’t take it down,” Young says. “They got a better sign.”

Young, who is African American, was proud of how the CA stood firm in that moment, just as it has throughout its history. And she credits Gurnee and LeCluyse for not only being her “campus parents,” but teaching her valuable lessons about the CA’s philosophical pillars: hospitality, faith exploration, and service and advocacy. “I didn’t really think about issues of social justice when I thought about my faith,” Young says. “Now it’s extremely connected. Any type of inequity when it comes to poverty or people generally persecuted in society, I really see my faith through that lens.”

Even though she graduated in 2015, Young found herself coming back to the CA throughout the past year. “Every time,” she says, “it’s like I’m coming back home.” She plans to continue to return, joining a core group of Penn alumni who care deeply about the CA.

Mullis, Sprunger, and Butler hope to remain active in their alumni years too, but their graduation has brought a very real concern about continuity—like a college sports team losing a deep senior class. “It feels like we’re in a perpetual state of rebuilding,” bemoans LeCluyse, who admits that she would “love for more students to know about us.”

Mullis agrees that the CA is “not a very well-known place” and that making it more familiar among the general student body is “something that we grapple a lot with here.” Butler believes the problem could be that the building is “hidden” away from the main campus arteries. And Sprunger thinks the Christian Association name itself can seem “a little intimidating,” and not necessarily something you’d equate with a progressive group.

And yet the progressive charge continues. In many ways, Gurnee says, the CA is now “doing the modern-day version of what was done a while ago.” For example, in the mid-1960s, the CA organized student service trips to Mississippi to register people to vote and build tent homes and facilities for striking tenant farmers who had been evicted. (One student, according to Lloyd, was former Penn President Judith Rodin CW’66 Hon’04.) More recently, its members helped rebuild homes destroyed by Hurricane Sandy, among other service projects. And while they don’t maintain their own settlement houses and camps anymore, the CA does offer a mentoring program for high-school students in West Philadelphia. And Bocage and other CA alumni, through a small foundation called the Dana How Social Service fund, currently fund West Philly kids’ attendance at a summer camp as well.

Pointing to Penn’s reputation for service, Gurnee ties it back to the efforts of Josiah McCracken and his successors. “Through camps and settlement houses and through ministry to international students, it really sort of emanated out of the CA,” he says. “I’m really hoping the 125th will allow us to showcase our history but also highlight the things we still do in support of Penn students and support of the Penn community.” (To share your CA memories, or for more information, email rgurnee@upenn.edu.)

During its official 125th anniversary celebration, which will be held during Homecoming weekend in November, the CA plans to recognize Chaz Howard, among others. It’s a fitting honor for Penn’s chaplain, who called the CA “deeply impactful” in his own spiritual journey and who firmly believes the organization has played a “crucial” role in the University’s history. And even if the Christian Association today might not be exactly what it once was, he knows that it will continue to be on the front lines of the causes it believes in, open its doors to anyone in need, and push forward in its mission, just as it has for the past 125 years.

“I think that as long as Penn’s here,” Howard says, “the CA’s going to be here too.”

Dave Zeitlin C’03 writes on a variety of subjects for the Gazette.