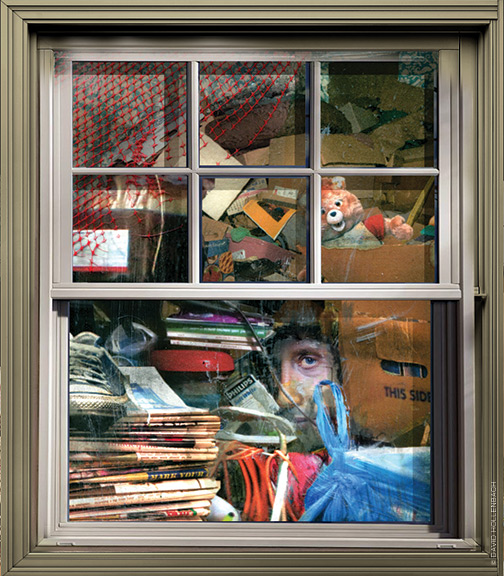

When a penchant for hanging onto things crosses a clinical line.

Studying hoarding has been like trying to catch a freight train, said Gail Steketee, professor and dean emerita at Boston University’s School of Social Work, during a Wolf Humanities Center lecture last fall titled “Buried in Treasures: When Stuff Takes Over.”

“Once we realized that hoarding was a serious problem that we needed to pay attention to, and once the research started in the late 1990s … it just took off, and we were running as fast as we could to catch up.”

Steketee is an expert on treating obsessive-compulsive spectrum conditions, specifically hoarding disorder, and she is the author of numerous books on the subject, including Stuff: Compulsive Hoarding and the Meaning of Things, coauthored with Randy Frost.

In fact, it was thanks to Steketee and her colleagues’ research that hoarding disorder was included in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders in 2013, colloquially known as the bible of psychiatry. Its primary feature is difficulty discarding items, resulting in disorganized clutter, distress, and impairment.

One in 20 people in the United States has a hoarding problem, she asserted. It frequently starts in preteens and teenagers who keep things “much, much longer” than their peers, eventually “accumulat[ing] enough so that they couldn’t move around the bedroom.” The disorder peaks in middle age.

People hoard clothes, shoes, newspapers, mail, food, take-out containers, plastic bags—everyday items that they can’t part with or feel they will need one day. (Animal hoarding is considered a “special manifestation” of hoarding disorder, and is difficult to study, Steketee said, because after it becomes criminal, people are usually unwilling to discuss it.) Their reasons for saving things are “the same as yours and mine,” she said. The items may be sentimental, useful, or beautiful and thus hard to let go. One woman anthropomorphized her yogurt cups and felt guilty throwing them away.

Hoarding affects not only the one doing it, but also family members and the community, putting adjacent neighbors at risk of insect and rodent infestations, and creating fire hazards. Steketee told the unfortunate story of a man whose rooms and halls were so jammed that firefighters could not enter to save him when his house caught fire, and he perished in the blaze. And in a highly publicized case in the 1940s, the two Collyer brothers were found dead in their home after their possessions collapsed on one—causing the other, who was blind and paralyzed, to die of starvation. Other people have become homeless or estranged from family members.

Hoarding often gets lumped in with obsessive-compulsive disorder, but they are two distinct mental illnesses. One of the differences, Steketee said, is that those who hoard often lack what psychiatrists call “insight.” That is, they have no awareness of their illness, as is also typically the case with patients with psychosis and bipolar disorder. This makes treatment difficult. And it is also why forced cleanouts are often upsetting to patients and can even lead to suicide attempts.

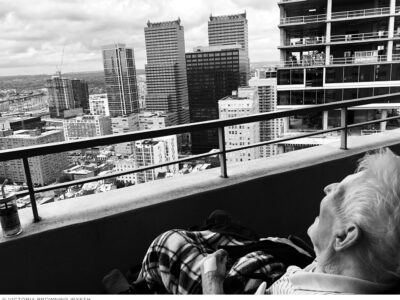

In a study of 62 elderly hoarders, social service providers reported that cleanouts by outside organizations helped only 15 percent of them. If safety or legal reasons mandate a cleanout, Steketee said, it is best to involve the afflicted person as much as possible in deciding what to keep and what to toss.

Trauma is not a typical cause of hoarding, she said, but it can sometimes play a role. “We had an instance, for example, where a woman was raped in her own home by a stranger,” Steketee explained. “She walled off the whole second floor of her house where that happened, and gradually that wall of stuff spilled into the lower floors and the whole place was covered. It was clear that was a triggering event for her.”

One common comorbid mental health problem, however, is major depressive disorder. Fifty percent of people with hoarding disorder, she said, are also depressed.

It is perhaps for this reason that Steketee and her colleagues have found cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to be so effective. CBT uses short-term goals to change thinking patterns, which in turn affects behavior. It can take about a year, but after 26 sessions of CBT, most people will no longer fit the clinical criteria for hoarding disorder.

So how do you know when your collection of Beanie Babies has crossed over into hoarding? Steketee herself admitted she collects antique fans. The difference, she said, is that collections are often themed, planned, organized, and not distressing.

“All mental illness runs on a continuum,” she said. But when people can no longer use their homes in the way that they used to—such as having nowhere to sit in the living room because the furniture is piled high with clothing, or not being able to use the stove because it’s covered in papers—that’s called impairment. That’s when you know you’ve crossed the line.

“We all have memories, and we like being reminded of things we found pleasurable,” she said, musing on the emotional resonance certain objects can have in our lives. But “in many ways, we don’t need objects for that. All we need is a reminder somewhere, sometime.” —NP

As a Professional Organizer for the past 34 years, I’ve worked with hundreds of hoarders. They exist in every type of community, every type of job and also the entire socio-economic spectrum.

I’ve discovered that many (if not most) of my hoarding clients were definitely triggered by some type of tramma… unexpected change, enormous loss, and/or sexual abuse, molestation or rape.

Yes, working with them can be a very slow, laborious process. I speak very candidly with these clients, make agreements for mutual common goals, and encourage them to celebrate every bit of forward momentum.

It’s both a physically & mentally very exhausting process, but oh so exciting when they “start to see light at the end of the tunnel.”

So worth it!

MER

RossowResources.com