A new book examines a forgotten component of the labor movement.

By Julia M. Klein | Sharon McConnell-Sidorick CGS’97 grew up in Philadelphia’s blue-collar neighborhood of Kensington, surrounded by shuttered hosiery mills.

In the 1920s and ’30s, the mills had been the epicenter of a thriving industry, the largest in Philadelphia. But like most of her neighbors, McConnell-Sidorick never realized the key role those factories and workers had played in the history of the American labor movement and the New Deal. “This history,” she says, “had just been lost.”

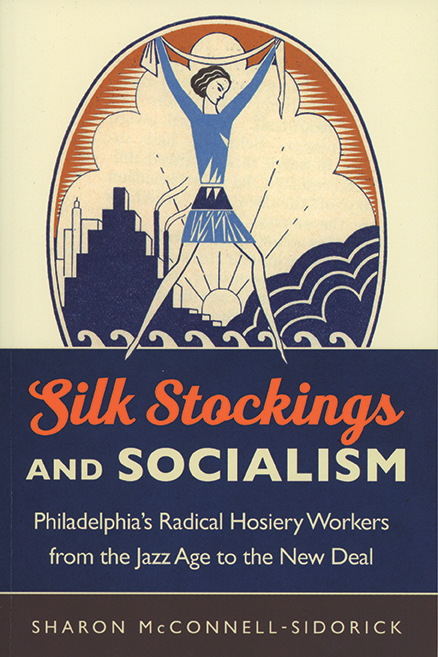

Her new book, Silk Stockings and Socialism: Philadelphia’s Radical Hosiery Workers from the Jazz Age to the New Deal (University of North Carolina Press), seeks to remedy that omission. The book explores the links among working-class culture, union struggles, and other forms of social activism in the city’s hosiery industry. “It gave me back a part of my heritage,” says McConnell-Sidorick, the daughter of a union truck driver who had never expected even to attend college.

In Silk Stockings and Socialism, McConnell-Sidorick examines the history of the hosiery union through something of an anthropological lens, thanks to her undergraduate major at Penn. She attributes the expansion of “full-fashioned” hosiery, originally a luxury industry, to demand created by the shorter hemlines of flappers. Hosiery workers—many young, many female—were themselves participants in the Jazz Age culture of smoking, drinking, and dancing. “Popular culture does come down into the working class, especially in a city like Philadelphia,” McConnell-Sidorick says.

Young workers were the union’s largest demographic in the 1920s, and it adapted accordingly, sponsoring a recreation program that included sports, picnics, and dancing. “They would have jazz bands, jazz dancing—and alcohol,” McConnell-Sidorick says. “This was in the middle of Prohibition, but in Philly nobody paid attention to Prohibition.”

In the 1920s and ’30s, women had to fight for equality in factory pay and union representation, but those battles were largely won, she suggests. “The modern woman … became a labor heroine,” McConnell-Sidorick writes, a role confirmed by the female figure at the center of the hosiery union’s Art Deco logo. (Racist hiring practices and work hierarchies were less malleable, though the union did support anti-lynching and voting-rights legislation.)

A major hosiery strike in 1933 helped lay the groundwork for the 1935 Wagner Act, which established the National Labor Relations Board and guaranteed the right to unionize. “They were first out the gate,” McConnell-Sidorick says of the hosiery union. “They brought the industry to its knees.” The expanding union changed its name from the American Federation of Full Fashioned Hosiery Workers to the American Federation of Hosiery Workers in 1933. And it began staging what were known as “Gandhi strikes,” notably a 1937 sit-down strike whose tactics prefigured later antiwar and civil-rights protests.

The hosiery union helped found the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1935. McConnell-Sidorick says that its ambitious agenda—including support for women’s rights, a minimum wage, Social Security, healthcare, and fair housing—influenced the contours of the New Deal.

A 66-year-old independent scholar who lives in Maple Shade, New Jersey, McConnell-Sidorick received her doctorate in history from Temple University, where Silk Stockings and Socialism began as a dissertation. But its inspiration was her longtime friendship with the late Alice and Howard Kreckman, retired hosiery workers and committed unionists who had entered the Kensington mills at age 14. They participated in strikes, lived in model union housing, and were still agitating for left-wing causes in their 80s and 90s. McConnell-Sidorick met the couple in the nuclear-freeze movement in the 1980s, and they bonded over their shared origins and social activism.

“Two absolutely amazing people,” she says. “Howard was a socialist. Alice said she was ‘left.’”

McConnell-Sidorick’s own earlier activism, in the 1970s, had included membership in a group called the October 4th Organization, which campaigned against police brutality and held consciousness-raising sessions for women. McConnell-Sidorick met her husband, who worked in information technology, through the group.

In 1987, when their daughter was 6 and their son 10, she enrolled at Burlington County Community College to study information systems—and discovered she loved history, anthropology, art history. So she applied for one of Penn’s Bread Upon the Waters scholarships, a program founded by Elin Danien CGS’82 G’89 [“Danien’s Daughters,” Dec 1997] that helps women over 30 return to school on a part-time basis. McConnell-Sidorick, then in her 40s and working in an insurance office, was a perfect fit.

Although she would eventually graduate from the University summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa, she had to struggle to be taken seriously. When one anthropology professor called her “a bored suburban housewife,” the late Bernard Wailes, an associate professor of anthropology at Penn who became her mentor, encouraged her to push back.

“I stood up to him, and I think he respected me more,” she says of the professor who had denigrated her. “I ended up taking two courses from him, and I aced them both.”

In Penn’s Master of Liberal Arts program (she completed the coursework but not the capstone project), an American oral-history course sparked her switch into history and her entrance into Temple’s doctoral program.

Years earlier, when McConnell-Sidorick had first learned about life in the hosiery mills from the Kreckmans, she recalls saying: “I can’t believe I don’t know any of this—that none of us knew any of this … I can’t believe this hasn’t been written about.” At that point Howard Kreckman turned to her and said: “I guess you’re just going to have to write it.”

Finally, she was ready. To research the hosiery workers, including Kensington’s own Branch 1, McConnell-Sidorick drew heavily on the University of Pennsylvania Archives. There she discovered the extensive oral histories and economic data collected in the 1920s and ’30s by the Wharton Industrial Research Unit, led by the economists George Taylor and Gladys Palmer. Also indispensable, she says, were union records housed at the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison.

On September 7, McConnell-Sidorick will discuss her book at the Penn Book Center; joining her will be Nathaniel Popkin C’91 GCP’95of Hidden City Philadelphia. She also has organized a panel in Washington for the American Historical Association’s annual meeting in early January, titled, “Reimagining Philadelphia’s Labor History: How Including Trolleymen, Black Wobblies, Flappers, and Trashmen Turned the Historiography on its Head.” The panel will be chaired by Walter Licht, the Walter H. Annenberg Professor of History at Penn.

Over time, as in other industries, modernization eliminated hosiery jobs, McConnell-Sidorick says. Factories also moved south, where organizing was more difficult, especially after passage of the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act. Nevertheless, she says, “I think it’s important that history is known—and also that [union members] really did contribute to making change,” a perspective with implications for the present. “We do have rights as citizens—change can be made, and people can participate and have a more democratic society. You can change things.”

Julia M. Klein is a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaMKlein.