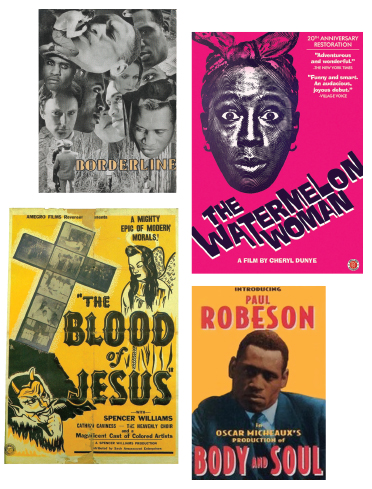

From Body and Soul to The Watermelon Woman, a film series explores the history of cinema by and for African Americans.

To the dismay of local preservationists, there’s not much left of Philadelphia’s fabled Royal Theater. The once grand Art Deco lobby is just a skeletal neoclassical façade whose brick arches and iron grillwork are temporarily enveloped by scaffolding.

With the site, on the 1500 block of South Street, destined for retail and residential development, only traces of the original, long-shuttered 1919 building will remain. Before closing in 1970, the Royal was a leading venue for live entertainment and movies geared to African Americans. More recently, it has served as one inspiration for a four-film series at Penn this winter titled “Reviving and Reviewing the ‘Race Film.’”

Like the theater itself, “a lot of these films have been lost, or have been poorly preserved,” says lead curator Iggy Cortez, a doctoral student and film and media scholar in the history of art department. Cortez says he lives near the Royal and was saddened by its fate.

The term “race film” is a loose designation for films with predominantly black casts marketed to black audiences from the 1910s to 1940s, Cortez says. “These are films that are interested in representing African-American life without whiteness being a point of reference—or without race relations being the primary point of reference,” Cortez says. Instead, these filmmakers are “interested in the complexity, the richness, and the fullness of African-American life.”

The series is being co-presented by the Wolf Humanities Center (whose theme this year is “Afterlives”) and the Cinema and Media Studies Program in collaboration with Lightbox Film Center at International House Philadelphia.

An estimated 500 race films were made—many produced, directed, and scripted by African Americans—but only a fraction of the total survives. The most well-known of the era’s independent African-American filmmakers was the Chicago-based Oscar Micheaux, who had more than 40 film credits. His silent film Body and Soul (1925), which marked Paul Robeson’s screen debut, is part of the Penn series.

Long considered lost, one of Micheaux’s most famous films, Within Our Gates (1920), a refutation of D.W. Griffith’s notoriously racist The Birth of a Nation (1915), was rediscovered in a Madrid film archive in the 1980s.“People find reels of [these] films all the time,” says Cortez. “The contingency of finding these films, the fact that a lot of these films were lost and then re-found, is definitely part of the way in which people think about race films.”

Pioneers of African-American Cinema, a project launched in 2015 by independent film distributor Kino Lorber to restore, rescore, and digitize a set of race movies, was another influence on Cortez. Two of its restorations, Spencer Williams’s The Blood of Jesus (1941) and Body and Soul, are being shown at Penn.

These two films embodythe “Afterlives” theme of the Wolf Humanities Center in their subject matter: Christianity and its promise of an afterlife. Yet another twist on the topic is the idea of artistic afterlives, Cortez says—in this case, the influence of American race films across time and geography.

That emphasis explains the inclusion of the final two films, neither of which meets the definition of a race movie. Borderline (1930) , directed by Kenneth MacPherson, is an avant-garde silent film set in a small Swiss town rife with tensions. It stars Robeson but has a predominantly white cast, including Hilda Doolittle CCT1909, the Imagist poet. The narrative is elusive, since the film has almost no intertitles. It does feature lots of close-ups, montage sequences influenced by the Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, and a jagged, atonal score. “The film claims to be about a bunch of themes, including race relations, but it’s really, for me, more about montage itself,” Cortez says.

The Watermelon Woman (1996) is Philadelphia filmmaker Cheryl Dunye’s mock-documentary tribute to a fictive black lesbian star from the era of race films. Chronicling two parallel interracial love affairs, it draws on seemingly genuine archival photographs and film clips to construct a usable cinematic past. The Watermelon Woman addresses “the way contemporary filmmakers inherit the legacy—or try to find a legacy when the archives may not exist,” Cortez says.

He notes that the category of race movies is a contested and unstable one, and sometimes also is used to encompass films marketed to Asians and other minority groups.“It’s not a self-conscious movement,” Cortez says, but rather involves “scholars trying to draw patterns historically from a range of disconnected films.”

The films themselves are often more sophisticated than they initially seem, says Cortez, who worked on the series with Eleni Palis, a doctoral candidate in English, and Alex Kauffman G’17, a postdoctoral fellow at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The Blood of Jesus is a case in point. It tells the story of a woman in a rural Southern community who is accidentally shot by her husband. Hovering near death, she experiences the contrasting lures of heaven and hell while members of her church community gather in prayer and song.

The film “purports to be a tale of moralism and warns against the excesses of a hedonistic lifestyle,” Cortez says, but demonstrates “a complicated relationship to religion.” So enticing and “spectacular” are the scenes of hell, set in an urban jazz club, that “they undermine their supposed message,” he argues. And although the cinematography has “a throwback feel,” he says, the interpolation ofdiaphanous inserts of heavenfroman Italian film anticipates a hallmark technique of postmodernism.

Micheaux’s Body and Soul, which takes the form of an old-fashioned Victorian melodrama,also raises modern questions about religion and the misleading nature of appearances. The film’s faux minister, played by Robeson (who also portrays the heroine’s virtuous suitor), is actually a con man, a thief, and a rapist. “The film shows a lot of conflict towards religion,” Cortez says. “Micheaux is interested in skepticism of authority and people who play into authority. Duplicity and not trusting appearances is something that recurs through a lot of his films.”

It’s been said that the decline of segregation—in both Hollywood itself and in movie theaters—heraldedthe end of race films. “Yes and no,” responds Cortez, who notes that in the 1950s mainstream movies were still not particularly integrated, but changing audience tastes and financial factors spelled the death of independent African-American cinema.

Cortez says students are often surprised to learn of the existence of these films. Now, he says, “I’m interested in bringing that history to a generalist audience.” —Julia M. Klein