Third in a 110 part series.

A new look for itself, a big win over the Crimson, and a visit from Teddy Roosevelt highlight Old Penn’s third year.

We assume that short attention spans and rapid shifts in fashion are contemporary phenomena, but after just two years of publication Old Penn decided to tinker with the brand, and came up with an interactive gimmick to do so—launching a contest for readers to win $10 by designing a new “heading” for the paper. The winner: architecture student Hans A. Gerke, who was selected by a panel that included noted architect and Penn professor Paul Cret from 10 entries in all.

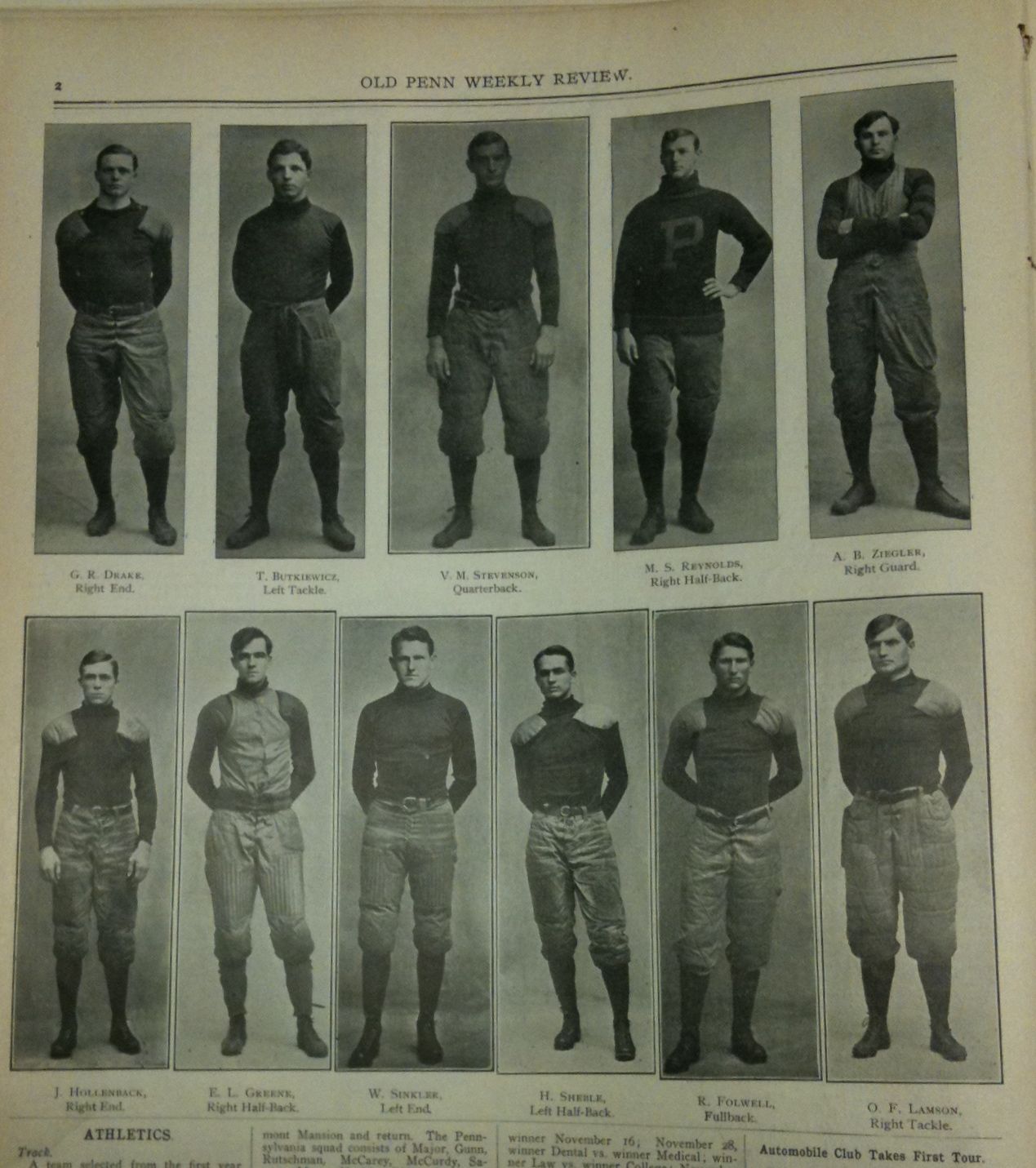

Breaking a string of six consecutive losses, Penn’s football finally team defeated Harvard, 11-0, occasioning what sounds like quite a party: “Can anyone blame the students for the wild celebration that kept Philadelphia awake on Saturday night, or the parades, and the bonfires that continued until Tuesday morning, while study was suspended.”

If things weren’t equally festive in the world of roundball, that was to be expected: “Though the basket ball team has been defeated by Yale, Harvard, and Princeton, it should be remembered that the sport has only been recognized at Pennsylvania for about a year.”

A Google-like proposal by the New York Evening Post to make “facsimile” of manuscripts and rare books was the subject of a letter from English professor Felix Schelling C1881 published in the paper, who wrote approvingly of the project “to duplicate, by photography, the literary treasures of the Old World, to the end that their contents may be saved from deterioration and the risk of destruction.”

Schelling was already a well-established figure on campus, but 1904 saw the arrival of another legendary faculty member, whose sculptures—including the youthful Ben Franklin, which stands outside Weightman Hall (see below)—remain among the most recognizable campus landmarks: R. Tait McKenzie, who came from McGill University to take the position of director of physical education.

Old Penn continued to beat the drum for the University’s phyiscal expansion: “The graduate of years ago living away from Philadelphia has no conception of what Pennsylvania is to-day … To-day the physical equipment of the University is unrivaled—and yet it cannot be doubted that the University is just beginning to grow.”

The Wharton School moved into Logan Hall, formerly medical space, during this year; the school’s endowment was also increased from $200,000 to $500,000 by benefactor Joseph Wharton, picture on the front page fpr October 14, 1904.

The new gymnasium was also dedicated, named to honor a $50,000 bequest by William W. Weightman. The building’s cost of $600,000 apparently raised some eyebrows, judging by Old Penn’s editorial counterpunch: “Phyical education is quite as much a part of education as the work of the classroom and the lecture room.”

(In another editorial, the paper chastised students for being indifferen to athletics and interested only in “obtain[ing] from the teaching staff the utmost farthing’s worth of instruction,” leading one to wonder who was setting those bonfires, etc., above.)

A story on the Provost’s annual report casts a look back 15 years, noting not only that the student population had grown from 1,000 to 3,000 (including an increase in the College from 429 to 1,490) and the teaching staff nearly doubled from 178 to 325 since 1890, but that the nature of education had changed as well, from just taking notes on lectures to “something in the way of practical work which the student has to do outside the classroom,” even “papers prepared from time to time” reporting on library texts.

Though it teetered on the brink of extinction at various points along the way, for a century Penn’s main ceremonial occasion aside from Commencement was known as University Day, which took place in February and honored George Washington’s birthday. (Washington, as was explained periodically in Old Penn and later the Gazette, had made multiple visits to campus and had been awarded an honorary degree by the University.) The occasion would eventually peter out in the 1930s, helped along by the Depression’s belt-tightening and a growing sense that if any Founder should have his Day at the University, it should be Franklin.

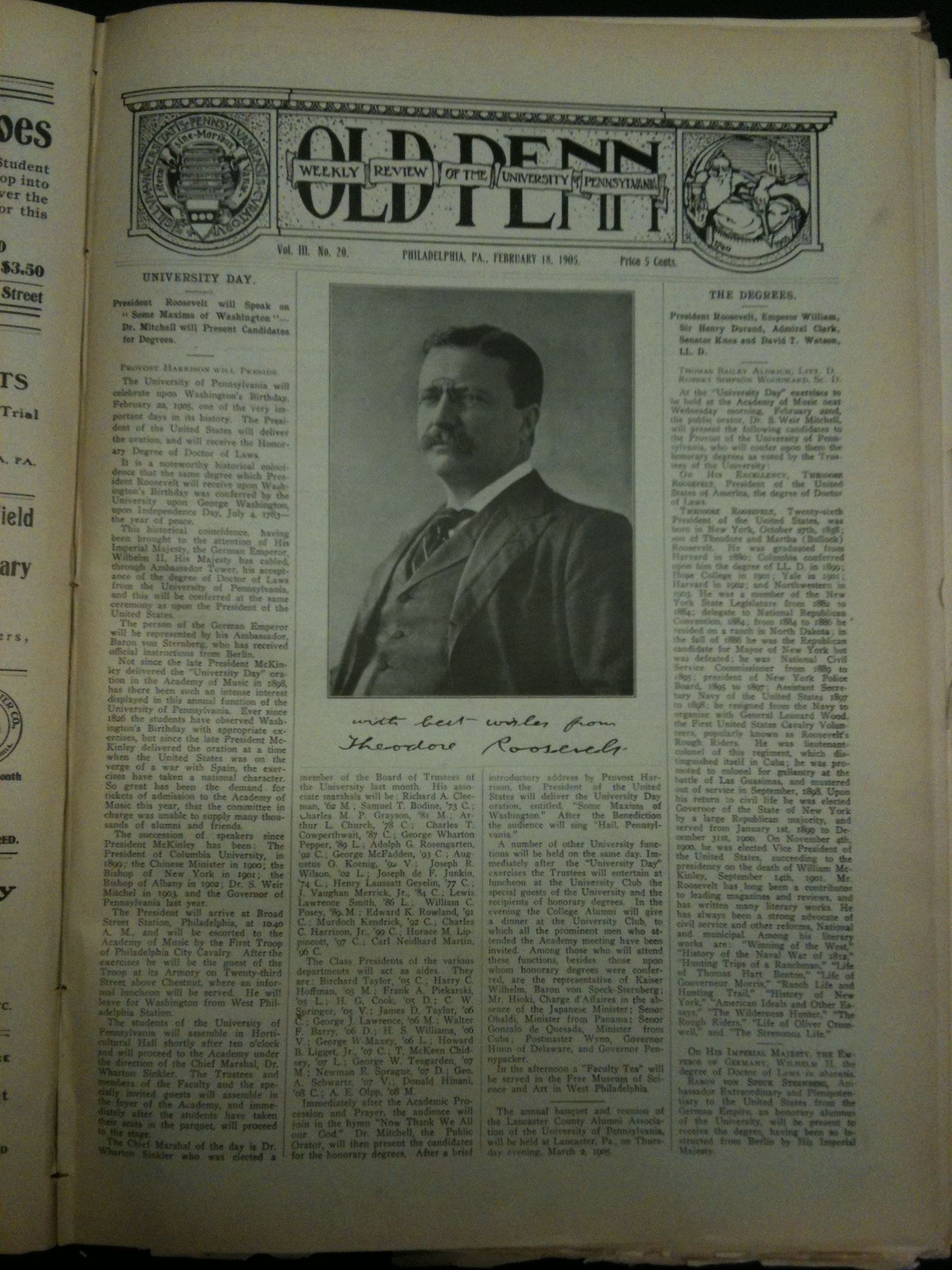

The 1905 edition of University Day was probably the gold standard, featuring then-President Theodore Roosevelt as the main speaker—on “Maxims of Washington”—and Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany among the honorary degree recipients. Certainly Old Penn’s editors thought so: “The reputation of the University of Pennsylvania—already far and wide established as a pioneer of progress—has received an added stimulus from the notable success of her last ‘University Day.’”

The 1905 edition of University Day was probably the gold standard, featuring then-President Theodore Roosevelt as the main speaker—on “Maxims of Washington”—and Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany among the honorary degree recipients. Certainly Old Penn’s editors thought so: “The reputation of the University of Pennsylvania—already far and wide established as a pioneer of progress—has received an added stimulus from the notable success of her last ‘University Day.’”