What’s more frustrating than playing Ivy League men’s basketball in the same era as Bill Bradley? Winning the University’s first official Ivy championship the year after he graduated, and then being kept out of postseason play because of a fight between the League and the NCAA. Fifty years later, Penn’s 1965-66 squad still wonders what might have been.

BY DAVE ZEITLIN | Photographs courtesy Penn Athletics

Basketball, as it usually does, surrounds Stan Pawlak C’66 as he settles into a corner table at the New Deck Tavern on the last Saturday before Christmas. Behind him, on the TV, Virginia is playing Villanova—a team that, back in his playing days for Penn a half-century ago, was on the other end of one of his favorite college wins. And just as soon as he’s done with his lunch, he’ll walk the couple of blocks to the Palestra to call a Penn hoops game on the radio.

The game itself is not especially appealing—Penn is hosting Division III Ursinus (who they’ll beat 73-66)—but that doesn’t deter Pawlak, who’s never been in it for the glory. One of his favorite things about calling games—which he’s been doing for several decades—is joining the players and coaches on weekend bus trips in the dead of winter to Ithaca or Hanover or any of the other freezing, unglamorous stops on the Ivy League road tour. “Is it comfortable on the bus?” he says between bites of a corned-beef Reuben. “No. But it wasn’t 50 years ago either.”

Fifty years.

Sometimes he has a hard time wrapping his head around just how long it’s been since he played his final basketball game for Penn. He likes to say that he doesn’t expect today’s players to know a thing about him because, well, what did he know about the 1915-16 team during his senior year?

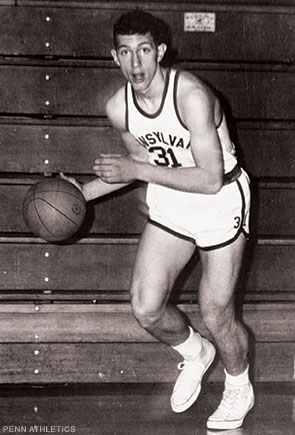

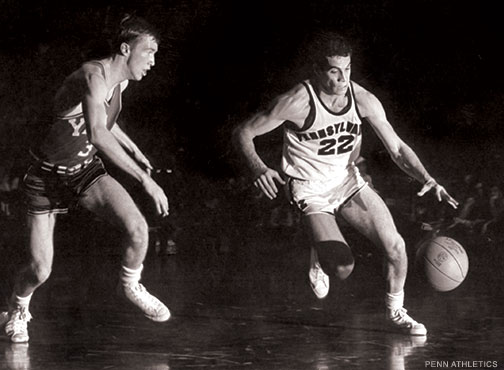

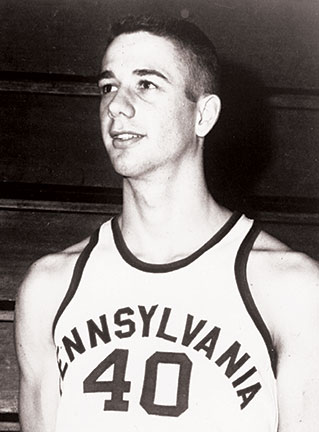

But Pawlak—one of the best players ever to wear a Penn uniform—is short-changing himself. The 6-foot-3 small forward remains etched in the program’s record books, having scored more career points (1,501) than all but seven other Quakers, despite having only three seasons of varsity play (freshmen had their own team back then). And longtime Penn fans are well aware of the electrifying partnership he honed with classmate Jeff Neuman W’66 WG’67, a crafty point guard whose style was ahead of its time.

Less well-known, at least in its entirety, is the story of how Pawlak’s college basketball career—and those of Neuman and the other seniors on the 1965-66 squad—ended: with one of the most epic wins in program history being overshadowed by a political tug-of-war between the National Collegiate Athletic Association and the Ivy League. Fresh off the program’s first official Ivy championship, the Quakers were denied the opportunity to take their rightful place in the NCAA tournament.

And why? Then-athletic director Jeremiah Ford II C’32 G’42’s refused to comply with a new NCAA rule requiring all student-athletes to maintain a minimum grade point average of 1.6. While in practice that would not have been a problem for Penn’s players, the University’s beef was that the national organization should not determine institutional policy. The rest of the Ivy League shared this view—but Penn’s team was the one that got sacrificed to principle.

To varying extents, Pawlak and the other players sympathized with the League’s resistance to the rule—a regulation that author and former Daily Pennsylvanian sports editor Dan Rottenberg C’64 describes as “well-intentioned but really stupid.” But everyone agrees that it was a shame that they were caught in the middle of a battle they never wanted any part of, especially because Penn’s own academic standards were higher than what the NCAA was trying to establish anyway.

For Pawlak, the sting remains 50 years later—and the decision makes even less sense than it did then. “It’s funny,” he says. “The person I am now? I wish I were that person then. Someone with experience. Someone that’s been around the block two or three times. If I was that person, I would be sitting on Jeremiah Ford’s desk saying, ‘How can you do this to us? How can you do it? What point are you trying to make? An ideal? You’re not the one not playing. We’re the ones not playing.’”

With time, the snub has also become harder to deal with for Charly Fitzgerald C’66 GEd’69 WG’83, the shooting guard and defensive specialist on Penn’s championship team.

Fitzgerald still can’t get enough college basketball. He’s a season-ticket holder—and sometimes sneaks into practices—at the University of Virginia, where he worked in development for 28 years before retiring last year. Like millions of Americans, he’s enamored of the NCAA tournament, in which UVA has been a fixture in recent years.

But it sometimes pains him to follow March Madness knowing he should have once been a part of it, alongside his fellow seniors and their hard-charging coach, Jack McCloskey Ed’48 GEd’52. “Every year at tournament time, I feel that twinge,” Fitzgerald says. “I would be dishonest if I didn’t say it. It’s something that’s always left undone. It was a goal and an aspiration. It’s a once-in-a-life opportunity.

“And it just went by.”

The Championship Core

About three-and-a-half years before the drama of the 1965-66 season unfolded, Jeff Neuman confidently sauntered off the Palestra floor, stopping on his way to the locker room to playfully rib McCloskey.

“We’re gonna beat you.”

Neuman was then the point guard on Penn’s freshman team. And along with classmates Pawlak, Fitzgerald, and John Hellings CE’66 GCE’67—the future core of the 1965-66 championship squad—he was showing off all of his considerable talents during the annual freshman vs. varsity game.

In the end, the freshmen lost—barely—to Penn’s very good 1962-63 varsity squad, led by Rhodes Scholar and future novelist John Edgar Wideman C’63 Hon’86 [“Wideman on Campus,” Jul|Aug 2000], which won 19 games and a piece of the Big 5 championship. But “we scared the hell out of them,” Pawlak recalls.

Despite being on the other side of that scare, McCloskey surely enjoyed seeing his new recruits take it to his veterans. After all, luring some of those guys to Penn hadn’t been easy.

Neuman was set on attending New York University, which then had a strong Division I program. It wasn’t until visiting Penn “as a courtesy” and shaking hands with McCloskey between games of a Big 5 doubleheader that he changed his mind, realizing he needed a tough and “truthful” coach to take the next step after often getting mixed messages at Altoona High.

“His presence was so powerful that I just said, ‘Man, I want to play for this guy,’” says Neuman, calling it one of the most important meetings of his life. “He was tough and he was involved and he would look you in the eyes and there was something so authentic about him. With McCloskey, it was like, ‘Man, this is a guy you’d run through a wall for.’”

Hellings, a 6-foot-9 center from Bucks County, was also close to going elsewhere—famed hoops coach Lefty Driesell, then at Davidson College, was hot on his trail—before being persuaded by McCloskey and top assistant coach Dick Harter Ed’53 to come to the Ivy League instead. He proved to be a critical piece of the puzzle, starting alongside Pawlak and Neuman for most of his four years at Penn and doing the dirty work of grabbing rebounds and, like Fitzgerald, playing solid defense—even if he didn’t always look the part.

“He was so unorthodox,” recalls Decker Uhlhorn C’69, who worked for many years for Penn Athletics and was on the freshman basketball team in 1965-66. “His knees were going one way, elbows were going another. But he was a force. He was a hell of a role player. And I think one of the most underrated players was Charly Fitzgerald. He did everything—in the trenches, score when he needed to score, stop the guy who needed to be stopped. He truly was the glue.”

Those two players were certainly vital because, as Hellings says, “If we had five guys like Jeff and Stan, we probably wouldn’t have done as well.” That’s not a knock against Neuman and Pawlak; it’s just the reality that there wouldn’t be room on one court for any more offensive superstars. And that’s exactly what they were: superstars.

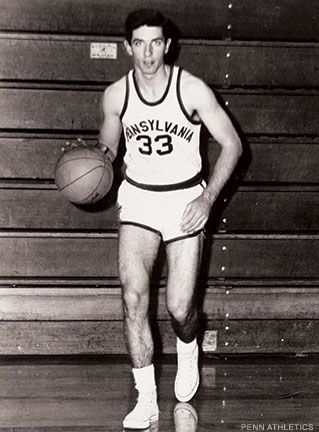

Those who watched Neuman play say he was doing things with a basketball—behind-the-back passes, flashy dribbling—that were almost unheard of at the time. (Hellings remembers him taking some criticism for this, but Neuman insists McCloskey had “not a qualm about it.”) And Pawlak knew just where to go to receive those passes, especially on Penn’s brutally efficient fast breaks, and to put the ball in the basket once he did. After setting the freshman team scoring record, he went on to lead the team in scoring as a sophomore (16.7 points per game), junior (21.5) and senior (23.2).

“His motion was strong and sure,” says Neuman, who was no slouch at scoring himself, averaging 16 points per game in his three varsity seasons. “He really could get in position, and I had the ability to get the ball to him. We just knew what each other was doing. It was a strong relationship.”

The two were never friends away from the gym, and haven’t stayed in touch since college, but Pawlak agrees that the pairing always worked on the court, calling Neuman “the perfect player for me.” It also helped that he had a vast array of moves, including a head fake that often left defenders reeling. “I don’t think people thought I was gonna do what I did,” Pawlak says. “I really believe that with my whole heart. If you look at me, I was a 6-3 guy who at that time wasn’t really a good shooter, not real fast, couldn’t jump real high, didn’t look that athletic.”

Fitzgerald, who once told The Daily Pennsylvanian that it was “senseless to want to shoot with Jeff and Stan on the team,” insists that if Pawlak had been 6-7 or 6-8, he “would have been a star in the NBA.” Lance Laver C’66, the basketball team’s manager as well as the DP managing editor, agrees. He remembers honoring Pawlak with the newspaper’s player of the year award and announcing, “I now present this award to a player who, if he were three inches taller, would be on everyone’s All-American list.”

Pawlak’s nose for the basket, Neuman’s playmaking ability, Hellings’ rebounding, and Fitzgerald’s defense formed the central elements of arguably one of the best classes in Penn basketball history. “It was a good mix,” Hellings says. “We all recognized that, once we started playing with each other.” He also credits McCloskey’s coaching. “We were all a little strong-minded, but Jack was able to meld the group into a good team,” he adds. “At the end of the day, we all had differences in personalities and talent but it just kind of fit together.”

There was only one problem: Bill Bradley.

Getting Over the (Princeton) Hump

Following productive freshman campaigns from Pawlak, Neuman, and company, as well as the graduation of Wideman and several key varsity players, it was clear from the start of the 1963-64 season that, as Neuman puts it, “We were gonna be the engine of this thing.” But with only one upperclassman who was a key contributor—guard Ray Carazo C’64—the Quakers, perhaps predictably, struggled early on.

Neuman still remembers how “depressing” it was to lose five straight games early in the season before the Quakers opened Ivy play with a momentous 70-69 overtime win over Yale. For Neuman, who hit the game-winning foul shot in the final seconds, that win was “a big step” for Penn and even led to some tears of joy in the locker room.

But looming down the road was perhaps the best player in all of college basketball.

The first time the Quakers played nemesis Princeton during the 1963-64 campaign, they actually held the great Bill Bradley to 18 points—well below his average—with an aggressive box-and-one defense. But the Tigers still easily won both of their matchups with Penn that season—and the following one, too—en route to back-to-back outright Ivy League championships. As a senior in 1964-65, Bradley was named national player of the year and led the Tigers on a stunning run to the Final Four, before scoring a then-record 58 points in an NCAA tournament consolation game against Wichita State.

“I remember reading the Wichita coach saying, ‘We’ll let Bradley get his 30,’” says Fitzgerald, who typically matched up against Bradley. “After trying to keep him from getting the ball for so long, I said to myself, ‘Oh my God, he doesn’t know what he’s doing.’ And Bradley had 58 points. You don’t let Bradley get his 30, or he gets 58.”

The Quakers had gone 10-4 in the Ivy League in both 1963-64 and 1964-65. With Bradley gone—to Oxford, the New York Knicks, and a long career in politics—Penn’s battle-hardened seniors headed into the 1965-66 season with high expectations.

They were determined not to repeat the fate of the senior-laden 1962-63 Penn team, which blew its chance at McCloskey’s first Ivy title after getting stunned by Columbia at home in the season’s penultimate game. “I remember Stan and myself talking about that and saying, ‘Let’s not let that happen to us,’” Fitzgerald says. “If we have a chance to win in our senior year, we’re not gonna let down.”

Neuman had a similar, albeit slightly less nuanced, perspective heading into their much-anticipated senior seasons. “I believe I felt, ‘If we don’t win it this year, it’s ridiculous,’” he recalls. “‘Bradley’s gone, for goodness sake. What’s the excuse?’”

Boosted by the inside presence of junior Frank Burgess W’70 and sophomore Tom Mallison C’68, the Quakers notched impressive city wins over Villanova and La Salle. But it wasn’t always smooth sailing. Early in the Ivy season, they lost to a Bradley-less Princeton. Later, after reeling off seven straight conference wins, the Quakers fell to Cornell in their final road game.

The Ivy League’s New York road trip—when teams travel from Columbia to Cornell or vice versa between games—is a notoriously brutal 225-mile slog, and may have played a role. Fitzgerald remembers not sleeping at all after Penn’s 15-point win over Columbia the night before facing the Big Red. And Cornell’s old gym at Barton Hall was an excruciating place to play in. “A big armory,” Pawlak recalls. “An ice-cold place with no one watching the game. You could hear the hockey fans yelling from three buildings away.”

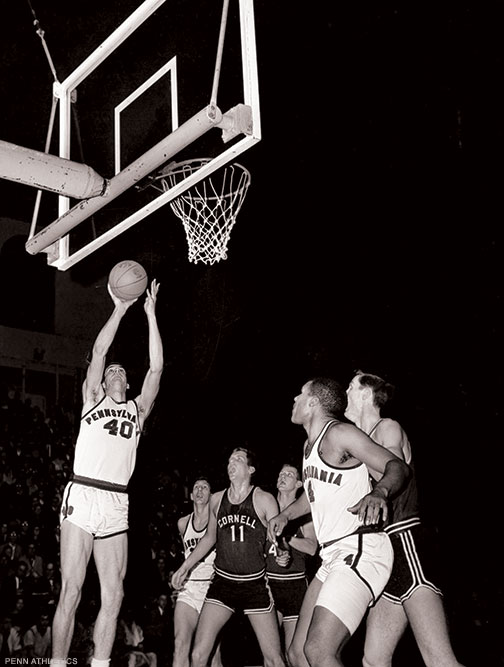

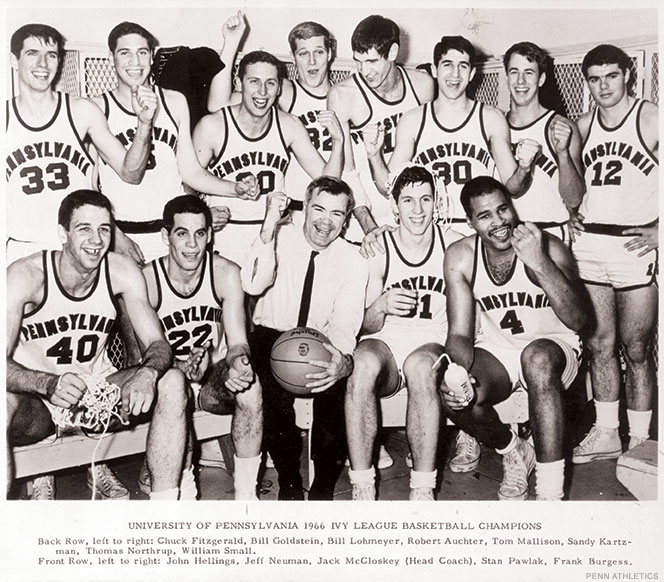

But that rough loss in the ice-cold Ithaca armory set up the ultimate drama, which took place in the friendlier confines of the Palestra just three days later—March 1, 1966—when Penn finally figured out a way to beat Princeton to capture the program’s first official Ivy League championship. (The league hadn’t been formally established when Penn came out on top in 1953.) Led by 18 points from Neuman and 15 from Fitzgerald (“I jammed a finger and I wasn’t myself,” Pawlak recalls), the Quakers earned a hard-fought 56-48 victory.

Considering the stakes, the opponent, the history, and the location, few Penn-Princeton games—or any Penn games, really—have matched this one. And the Quakers reacted accordingly, cutting down the nets and carrying their coach off the floor after being mobbed by fans. But even during the celebration, there was an ominous undercurrent.

In the first paragraph of his New York Times report of the game, Gordon S. White Jr. wrote: “Pennsylvania won its first Ivy League basketball championship in 13 years tonight but found itself in the position of possibly being like the pretty girl who was all dressed up with nowhere to go.” The Ivy League’s objection to the NCAA’s GPA requirement, which had been passed two months earlier, was well documented. And the NCAA had made it clear that failure to comply, in writing, with the new legislation would result in exclusion from NCAA championship events.

The uncertainly lasted for a couple more days as the Ivy League presidents and NCAA officials tried to negotiate a solution. The Quakers, who were scheduled to play Syracuse in the first round of the NCAA tournament in Blacksburg, Virginia, even held a practice after beating Princeton, and McCloskey flew to Buffalo to scout Syracuse. But the players could sense the outcome. “I could tell there wasn’t the normal intensity of practice,” Fitzgerald recalls. “It was highly suspicious.” Adds Neuman: “It was kind of a ghost town.” Their intuitions proved to be correct. After McCloskey delivered the message that his team wouldn’t be going to the NCAA tournament, the team’s five seniors—Pawlak, Neuman, Fitzgerald, Hellings, and Bob Auchter W’66 (who has since passed away)—went to Smokey Joe’s for a beer.

“I just saw it as a gross injustice,” says Uhlhorn. “To think you had to sit behind the Bradley team for two years, and then when you get your chance and you can really shine and get on a major stage and then someone takes it away for basically political and institutional fighting …”

He trails off, his irritation seeming to grow with each word.

Two Sides of the Story

Jack McCloskey knows the feeling.

McCloskey is 90 now, and when he picks up the phone he makes two things clear right away. The first is that he doesn’t hear very well anymore and can’t remember as much as he used to. The second is that he’s looking directly at a framed picture of the 1965-66 Penn basketball team, which hangs on his living room wall in Georgia.

“I forget things,” he says. “But I’ll never forget that.”

McCloskey had a great career in basketball after leaving Penn—including a wildly successful stint as general manager of the Detroit Pistons from 1979 to 1992 that included two NBA championships—but he says that team holds a special place in his heart.

“They were not only good basketball players but they had a sense of humor,” he says. “One time I mentioned to them that we were going to be the best. And that became a theme with them. One day, they said, ‘Hey Coach, do you still want us to be the best?’ I said, ‘Yeah, of course I do!’ If they did something else, they’d say, ‘Hey, was that the best, Coach?’ It was fun. It was great.”

The fact that that Quaker team—despite being “the best” in the Ivy League that season—never got to test themselves against the top teams from across the country pains McCloskey to this day. His animosity toward the Penn administration, specifically athletic director Jerry Ford (who passed away in 1997), also remains. He says that Penn’s disqualification from the NCAA tournament made him decide to leave his alma mater—where he had played football, basketball, and baseball in the 1940s—before he had another job lined up. “I had to leave the University, because I’d get in trouble with [Ford]. I’m an Irishman. I would have had trouble.” Though he was soon hired by Wake Forest, where he coached from 1966 to 1972 before beginning his NBA career, “I had nowhere to go at the time,” he says.

To coach a team for a decade with one goal in mind and then have it snatched away at the moment of achievement would be maddening for any coach, let alone one as ambitious and tough-minded as McCloskey. But while his former players understand his anger, it’s important to note that some of them—at least at the time—expressed some pride that Penn and the Ivy League did not capitulate to the NCAA. And the issues at hand, of course, went a lot deeper than a simple feud between Ford and McCloskey.

Writing in The Philadelphia Inquirer in the wake of the controversy, legendary sports columnist Frank Dolson W’54 stood up for Ford and came down hard on the NCAA’s executive director, Walter Byers. According to Dolson’s column and other newspaper accounts, the NCAA and the Ivy League had at one point reached a compromise that entailed the conference’s eight schools sending telegrams to NCAA headquarters stating that certain academic, admissions, and student-aid information would be provided to the NCAA.

But Ford, Dolson wrote, “suspected the compromise was really a trap” and sent Byers a telegram that flatly stated: “Pennsylvania will not comply with the 1.6 legislation.” Yale sent an identical telegram, prompting the NCAA to declare both schools ineligible for postseason competition. And although Ford was “tagged as the man who upset the agreement by an act of defiance,” his action was “vindicated” when Robert Goheen, Princeton’s president and de facto head of the Ivy League on the issue, said that the other six schools would back Penn and Yale, presenting a united Ivy front. “It’s easy to get lost in a welter of sentiment; to lose sight of the real issues,” Dolson concluded. “It took courage on Ford’s part to make what had to be, at the time, a difficult—and unpopular—move.”

Neuman was quoted in an article in the old Philadelphia Bulletin as saying that the players “were kind of happy the Ivy didn’t back down.” And the Daily Pennsylvanian wrote an editorial positing that the decision was the “only choice” because the NCAA’s position was “inflexible, inapplicable and unnecessary for the league” and was just another in a series of “foolish contrivances by a group of power-hungry men whose commitments to television and material benefits in general have often marred its true duty to the betterment of intercollegiate athletics.” (That assessment may sound eerily prescient to many people.)

Most important, Ford had the backing of Penn’s then-President Gaylord Harnwell Hon’53. According to the DP, Penn could have played in the NCAA tournament had Harnwell renounced Ford’s telegram. But instead he provided a statement to further explain Penn’s objection to the NCAA rule, declaring that it was intended for student-athletes on financial aid and thus should have no bearing on the Ivy League, where athletic scholarships are not given. For the same reason, he also balked at another piece of the NCAA’s legislation, which stated that an athlete is not eligible for a scholarship as a freshman if he doesn’t have a predicted GPA of 1.6 based on his high-school academic credentials.

In his own statement, Princeton’s President Goheen laid out the Ivy League’s objections to the rule, writing that there were three cardinal issues: “(1) Do you believe that athletes should be treated differently than other students? (2) Do you believe that an athletic organization should seek to determine academic policy? (3) Do you believe that a student with a low grade average should automatically be debarred from participation in sports and from financial aid, no matter his academic potential?” Goheen continued: “If your answers are ‘yes’ to these three questions, you will support the NCAA’s rule. If your answers are ‘No’ then you will understand why it is impossible for the Ivy Group institutions to accept the 1.6 legislation.” He went on to note that a single GPA standard for every college was unrealistic, and that it could prevent athletes from attending schools with more challenging academic programs—like, perhaps, the Ivies.

“To me, that was sort of the Ivy League’s finest hour, really,” says Dan Rottenberg, who had covered Penn basketball a couple of years earlier for the DP, and whose brother, Bob Rottenberg C’66, was sports editor during the 1965-66 season. “Every year there’s a championship in something and you get to go to the NCAAs. But this was really a unique situation, and the Ivy League really did stand up to the NCAA in ways that no member colleges do anymore.”

Rottenberg, who played football at Penn, sympathizes with the players and allows that it was “sort of a shame it happened the one year [when] Penn won the Ivy League.” But he’s always been a passionate defender of Ford, who was instrumental in making sure Penn was included in the formation of the Ivy League in 1954. One well-known impact of that decision was to ensure the end of big-time football at Penn, which led to Ford “becoming a pariah among the sports alumni,” says Rottenberg, whose Fight on, Pennsylvania: A Century of Red and Blue Football covers the history of the sport at Penn up to 1984 . Many alumni never forgave him for that; a year after the 1966 NCAA basketball spat, they engineered his dismissal.

“What I respected about Jerry Ford is he really saw the big picture,” Rottenberg says. “And that big picture is: What is the mission of this institution? The mission is education … He was in this position where he was keenly aware of Penn’s vulnerable situation within the Ivy League. Everyone else sort of took that for granted.”

Not Getting Their Due

On a cold night in January of this year, Stan Pawlak heard his name called over the Palestra loudspeaker and walked to the middle of the court. In honor of the 60th anniversary of the Big 5, each of the member teams—Penn, Villanova, Saint Joseph’s, Temple, and La Salle—invited former star players to represent each of the last six decades of Philadelphia basketball. Pawlak was Penn’s honoree for the 1960s, waving to the fans during a timeout of a Big 5 doubleheader, but he says he wouldn’t be surprised if many of them had forgotten what decade he played in.

“A lot of people, they know I played for Penn, but they think I played for the Dave Wohl-Corky Calhoun team,” says Pawlak, referring to the renowned 1970-71 squad that had a 28-0 regular season record before getting stunned by Villanova in the NCAA tournament [“Almost Perfect,” Mar|Apr 2011]. “They can’t go back” any further than that.

Pawlak believes that the 1965-66 Quakers get “overlooked a little,” surely in part because they didn’t get their chance to make a run on the national stage. He probably has a point. In the annals of Penn basketball, the teams from the 1970s—including of course the 1978-79 Final Four squad—get the most appreciation, with the Jerome Allen-Matt Maloney teams of the mid-1990s, which enjoyed some memorable NCAA tourney moments in their own right, not far behind.

Aside from a mention (1966 Team—NCAA Bid Spurned) on a wall-mounted timeline inside the Palestra, Penn’s first Ivy League championship team hasn’t gotten much recognition. And no ceremony marking its 50th anniversary was planned.

Hellings, who lives in Texas, has only been back to campus a couple of times since graduating, and hasn’t seen his old teammates since their 25th reunion. But he still laughs about the old running joke they had: “We take solace in the fact that we can proudly say that if we’d been in the damn tournament, we would have won it. We claimed the title that year. At the 25th reunion, we claimed the NCAA title.”

Had they actually played, it may have taken “a miracle” for Penn to win its first-round game against a loaded Syracuse team that featured future star Dave Bing, who averaged a whopping 28.4 points per game, and Syracuse’s current coach, Jim Boeheim. “But there’s no telling,” Helling says. “We had a few miracle games against some of the Big 5 teams.”

“They might have beaten our brains in, but who knows?” adds Pawlak. “It would have been fun.”

It’s a testament to the magic of the NCAA basketball playoffs that the former players still think about what could have happened. But the tournament is different now than it was 50 years ago. It was 22 teams, not today’s 68. There was no wall-to-wall March Madness coverage on TV. No ESPN bracketologists or Internet betting pools. So when the Ivy League winner didn’t go to the NCAA tournament just a year after the previous Ivy champion had made it to the Final Four, it didn’t generate anything like the kind of national attention it would today.

Television coverage wasn’t the only difference. The tournament itself wasn’t as glamorous—the NIT was still a big deal at the time—and neither was the life of the college athlete. Back then, almost all of Penn’s players were multi-sport athletes. Pawlak threw the discus for the track team. (He also washed dishes for four years in the dining hall.) Once, when he asked a professor what he could do to get his grade up, he was advised to “quit basketball and track.”

Fitzgerald remembers a similar interaction with a teacher, who wanted him to get a written excuse from the provost to miss a seminar the day Penn was scheduled to play in the NCAA tournament. (As it turned out, he was able to attend.) And a couple of days after the hoops season ended, he and Neuman both headed off to baseball practice. McCloskey was their coach.

“In today’s world, if [a conference winner] didn’t go to the NCAA tournament, there would be protests, there would be a backlash,” Pawlak says. “It would be a big story on ESPN. When we were there, that was it.”

There were some repercussions. Not only did McCloskey bolt, but Pawlak claims that Penn also lost a big recruit to Princeton, future NBA all-star Geoff Petrie. And the Quakers struggled for the next couple of seasons before beginning their decade of dominance in the 1970s.

Pawlak speculates that not getting a chance to play on the national stage may have hurt his chances to make an NBA roster. “I was always the last guy cut,” he says. Instead, he enjoyed a fruitful career in the Eastern Professional Basketball League (later renamed the Continental Basketball Association) before getting into coaching.

What Pawlak found most upsetting about the situation 50 years ago was that it unfolded without Ford ever talking to the players, who put up little resistance because they didn’t think there was anything they could do. (They did later get a letter of apology from President Harnwell, Fitzgerald says, which was “little consolation for not having played in the tournament.”) And the lasting impact of Ford’s big stand never seemed entirely clear to them, either.

A few other Ivy League teams were ruled ineligible for post-season play in 1966 and 1967, but none were as high profile as Penn hoops. (Princeton did compete in the 1967 NCAA tournament, winning a game while it was there.) And although there was some posturing to the effect that the Ivy League would leave or be expelled from the NCAA, within two years the 1.6 rule was amended sufficiently for the Ivies to come into compliance.

According to an article in the January 30, 1968 Cornell Daily Sun, the provision requiring student-athletes to maintain a 1.6 GPA in college was repealed while the clause that necessitated “predictability” of a 1.6 GPA for incoming student-athletes remained. The NCAA has maintained standards for high school students to receive athletic scholarships ever since, although the 1.6 rule was abolished in 1973 in favor of a 2.0 GPA standard, which later gave way to the more balanced Proposition 48, which also factors in standardized test scores.

Of course, the Ivy League has always maintained its own, higher, standards for admission. And Penn, too, has its academic requirements—made evident recently when sophomore guard Antonio Woods was declared ineligible in January due to “insufficient academic progress under University policy.”

Knowing all that, Pawlak concedes that the Ivy League’s objection to the NCAA trying to dictate uniform standards was “correct.” But he still feels like more could have been done to find a compromise, considering that his was the only basketball team ever affected by the dispute.

“We weren’t even [given] a thought,” Pawlak says. “What was best for us never entered into anyone’s mind. I mean, how can you not let us go?”

Still, Pawlak’s bitterness about the situation has never affected his attitude toward his alma mater. That much is clear when you see him on press row at the Palestra, smiling as he watches the sport that opened so many doors for him—even if one big one was forever sealed shut.

“The best thing I ever did was picking Penn and staying in the area,” Pawlak says. “I mean, if you want to write a dream story, we get into the tournament and we beat Syracuse.”

He pauses to think about it some more, visions dancing in his head of what it could have been like to play just one more college basketball game, 50 years ago. Or maybe two, or three …

“Yeah,” he continues softly, “that would be a dream story.”

Dave Zeitlin C’03 writes frequently for the Gazette.

My dad and I were at the penn-Cornell game whe. Wilt scored 100 in Hershey, Pa. Sid Amira, one of my favorite players (next to Mlkvy and John Wideman) got a three point play to send the game into overtime and an eventual Penn victory. Great memories!

I became single focused about going to Penn when I went to the Palestra at the age of 9. Our family traveled to Philly most weekends to watch my brother, Jeff Neuman, play basketball on a great Quaker team in the 60’s. The fast breaks, the shooting, the defense… it was utterly captivating.

I attended most of the games during my years at Penn in the 70’s and continued to love the thrill of sitting in the bleacher seats at the Palestra. As good as the teams were then, they didn’t have the magic of the Ivy League champs of 1966…

This was a very interesting article, as I’ve heard these events from the perspective of my father (Tom Mallison). The university/league caused this team to miss out on an tremendous opportunity. I think it would be a great idea for Penn to invite this championship team back and honor them.

Thanks again for writing this, Dave Zeitlin

I enjoyed your report on the 1961-62 season and the last Yale team to make it into the NCAA tournament. If I remember correctly they were 13-1 in the Ivy League that year with their only loss to us at the Palestra on James Joyce’s birthday in 1962. Ray Carazo played for us and he succeeded Joseph Vancisin as the coach of Yale basketball. Our coach, John William “Jack” McCloskey (born October 19, 1925), went on to be the architect of the two time NBA champion Detroit Piston bad boys as coached by the former Penn coach, Charles Jerome “Chuck” Daly (July 20, 1930 – May 9, 2009), who succeeded Dick Harter (October 14, 1930 – March 12, 2012), who in turn succeeded Jack McCloskey as Penn coaches. You probably should have mentioned Al Kaemmerlen, who was the Princeton captain in 1962 and a member of Ivy Championship teams his sophomore and junior years but fell short to Yale in his senior year. He was a member of the 1958 Pennsylvania high school championship team at my wife’s high school where she was a member of their class of 1960.

Of course, the 1961-62 season was the one season in the NBA for Frank Joseph McGuire (November 8, 1913 – October 11, 1994), who was the Philadelphia Warriors coach of Wilt Chamberlain on March 12, 1962 when Wilt scored 100 points. Frank McGuire started in Chapel Hill in 1953 after The Tar Heels lost on New Year’s Eve, 1952 to the Penn team coached by Howie Dallmar, the MOP on the last Stanford NCAA champion in 1942 as led by Ernie Beck, who is still the Penn scoring and rebounding leader. Of course Frank McGuire was succeeded by Saint Dean Smith.