Though Benjamin Franklin was known for many things, he wanted to be remembered as a printer. That’s one reason the University’s recent acquisition of the only known copy of his first printed work is such a coup. But there are other, equally important reasons, not to mention some pretty good stories behind the piece and its path to Penn.

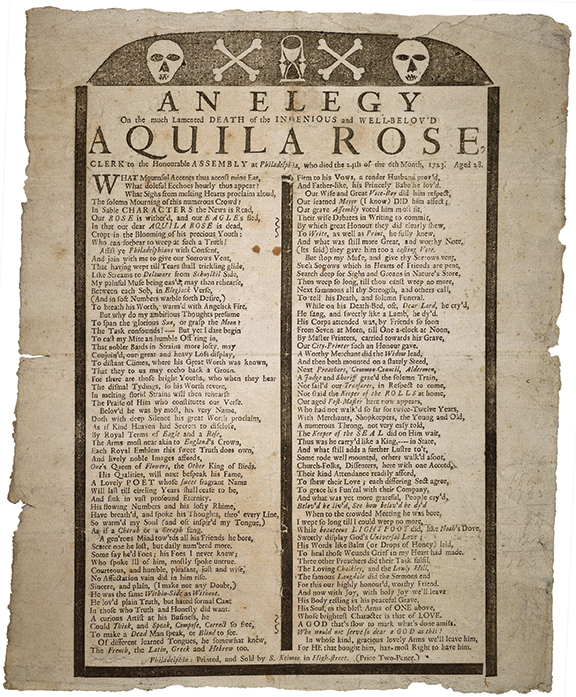

The 1723 broadside, which Franklin printed within days of his arrival in Philadelphia, is usually referred to as “An Elegy on the Death of Aquila Rose,” a young printer and poet whose passing shook the colonial city’s small printing community. But the full title is more evocative: “AN ELEGY On the much Lamented DEATH of the INGENIOUS and WELL-BELOV’D AQUILA ROSE, CLERK to the Honourable ASSEMBLY at Philadelphia, who died the 24th of the 6th Month, 1723. Aged 28.”

Had Rose not died when he did, Franklin might never have come to Philadelphia, and certainly not at that formative moment. In his Autobiography, he discusses the circumstances of his arrival in New York as an almost-penniless 17-year-old fugitive, trying to find work:

[ H]aving a trade, and supposing myself a pretty good workman, I offered my service to the printer in the place, old Mr. William Bradford, who had been the first printer in Pennsylvania, but removed from thence upon the quarrel of George Keith. He could give me no employment, having little to do, and help enough already; but says he, “My son at Philadelphia has lately lost his principal hand, Aquila Rose, by death. If you go thither, I believe he may employ you.”

Somewhat reluctantly, given his lack of money and the effort he’d already spent making his way from Boston, Franklin took Bradford’s advice. When he reached Philadelphia, he found that Andrew Bradford had hired an assistant and didn’t need him. By then the elder Bradford had arrived, and agreed to introduce Franklin to the other printer in town, Samuel Keimer.

Keimer’s printing-house, I found, consisted of an old shatter’d press, and one small, worn-out font of English which he was then using himself, composing an Elegy on Aquila Rose, before mentioned, an ingenious young man, of excellent character, much respected in the town, clerk of the Assembly, and a pretty poet. Keimer made verses too, but very indifferently. He could not be said to write them, for his manner was to compose them in the types directly out of his head. So there being no copy, but one pair of cases, and the Elegy likely to require all the letter, no one could help him. I endeavor’d to put his press (which he had not yet us’d, and of which he understood nothing) into order fit to be work’d with; and, promising to come and print off his Elegy as soon as he should have got it ready, I return’d to Bradford’s, who gave me a little job to do for the present, and there I lodged and dieted. A few days after, Keimer sent for me to print off the Elegy.

And so he did—with precocious skill, even embellishing the broadside with what experts believe were his own woodcut illustrations. The fact that he made the most of his first opportunity would have profound implications for history, as Mitch Fraas, special-collections curator at the Libraries’ Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts, explains:

“Franklin comes to Philadelphia and prints this. He ends up working in Keimer’s shop for several years. He lays down roots in Philadelphia. He does travel to London and then comes back to Philadelphia, but without throwing down these roots, is there a University? Are there all these knowledge institutions [including the American Philosophical Society and the Library Company of Philadelphia] that we depend on today?

“It’s fascinating to think of how precocious that is—a 17-year-old being asked to print something, and going the super-extra mile,” Fraas adds. “You can see why Keimer was so impressed and why Franklin remained around. A lot of early American printing is kind of jumbled or splotchy, especially in comparison to the European printers. This is quite a good print job, and really striking in the spacing and clarity.” As for the “very New England” graveyard-style illustrations (skulls and crossbones, an hourglass), he says: “this is not something Keimer has lying around his shop that Franklin just throws in. The iconography doesn’t match anything in Philadelphia at the time. Franklin was known to dabble in woodcutting, and it’s something he definitely could have done on relatively short notice.”

The fact that Franklin wrote such a detailed account of this episode makes it “particularly compelling,” notes Fraas. “He printed 900-plus things in his career, and I don’t think he talks about more than a couple in his autobiography, at least in this kind of detail.”

Though hardly anyone knows the name Aquila Rose today, his death prompted a surprisingly emotional outpouring from the printing community. In the “Elegy,” Keimer, the rival printer, tells his readers: “Then weep so long, till thou canst weep no more,” and describes the local printers carrying Rose’s body to his grave after the “Solemn Funeral.”

“You think of rival print shops as these sort of cutthroat relationships,” says Fraas. “But Aquila Rose was primarily Bradford’s pressman. And for Keimer to have this really deep emotional response to his only competition’s star player is remarkable.

“The lines about the mourning of the print trade are indicative of how tight-knit and important that professional identity was,” Fraas adds, emphasizing that Franklin “identifies for most of his life primarily as a printer. It’s something he takes pride in. Given that Bradford and Keimer traded Franklin around makes me think of the way Aquila Rose sort of brought Franklin into this—was there a spirit of cooperation engendered by this loss?”

Fraas has found himself wondering about the broadside’s brief moment in the Colonial sun.

“How many of these were printed?” he asks rhetorically. “How many people read the ‘Elegy’? Was it slapped on the side of buildings? Or was it passed around by hand amongst the printing community or the sort of elite Philadelphia community? In 1723, if you walked the streets of Philadelphia, would you have seen the skull and crossbones and ‘The Elegy of Aquila Rose’ adorning every tavern, on a board?” Either way, given the excellent condition of this sole remaining copy, “it almost certainly was never pasted up on anything.”

For the better part of three centuries, the only version of the “Elegy” seen by the public was a transcription by 19th-century Philadelphia antiquarian Samuel Hazard that had been reprinted (with a couple of errors) in various collections of early American poetry. Twenty years ago, a Philadelphia rare-book dealer named Carmen Valentino came across the real thing—in a scrapbook of Hazard’s.

Valentino, whose book business is located in the Port Richmond section of Philadelphia, contacted the University.

“Carmen has very fond feelings for Penn, and he’s someone the library has known for a very long time,” says Fraas. “We had a delegation head over to Carmen’s shop, and it was sort of electrifying to have him whip out this broadside and scrapbook. Carmen was very excited about conveying the story, and it was a great experience.”

Since Penn is not only one of the institutions founded by Franklin but one that continues to be “dedicated to his passion for the widest possible dissemination of knowledge and the promotion of learning,” said Vice Provost and Director of Libraries Carton Rogers in a statement, the Penn Libraries is “proud to build on his legacy and make this material open and accessible to the wider world.”

Two years ago, notes Fraas, the Libraries purchased the last thing Franklin printed—a copy of Jacques Barbeu-Dubourg’s Petit Code de la raison humaine, printed in 1782 when he was an ambassador to France—“so now we have the bookends of his career.”

During a brief exhibit that opened January 17 (Franklin’s birthday), the “Elegy” was displayed on the first floor of Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center alongside the scrapbook, which was opened to an evocative 1780 woodcut of Benedict Arnold being burned in effigy. Limited to three weeks because of the broadside’s fragility, the exhibit represented the first time Franklin’s printing debut had been seen in public since colonial times. Now that it has been digitized, it can be examined by anyone.

“The display and the digitization represent the knowledge continuum that the Libraries are carrying on,” says Sarah Leavens, the Libraries’ communications, marketing, and social-media coordinator.

“When people think of Penn, they think of Franklin, and they think of innovation and the importance of knowledge and learning,” says Fraas, “things that Franklin privileged above nearly everything else in establishing the University, the Library Company of Philadelphia, the American Philosophical Society.” After all, Franklin “gave one of the first five books that we have.”

He also took an enlightened approach to sharing knowledge. Since the Libraries’ collection represents “a good third of everything Franklin ever printed”—accessible to scholars and soon to be accessible to the public in digital form—it honors the way in which Penn’s founder “envisioned a University and a society working,” Fraas adds. “This is not a place that locks a broadside like this in a safe and tells people, ‘We have very valuable things here, and go away.’ I’m hopeful that tons of people will click on the link to the digitized thing and will see this for the first time.”—S.H.