Brett Perlmutter’s mission was to open up Cuba to the internet. To say that it was politically sensitive is an understatement. But the timing was just about perfect.

BY ALYSON KRUEGER | Illustration by Emiliano Ponzi

Brett Perlmutter C’09 had no idea why he was suddenly getting so much love from the crowd around him on a warm, humid day in Havana this past March.

“People were going up to Brett and practically kissing and hugging him,” remembers Ted Henken, a professor at Baruch College’s School of Black and Latino Studies who specializes in Cuban entrepreneurship. “Brett was going, ‘What the hell is going on here?’”

It didn’t take long to figure out that it had something to do with President Barack Obama, who was also visiting Cuba. He had already declared that “in the 21st century, countries cannot be successful unless their citizens have access to the internet.” Then, in an interview with ABC’s David Muir released the second day of his visit, Obama applauded one American company for making progress in expanding access: Google.

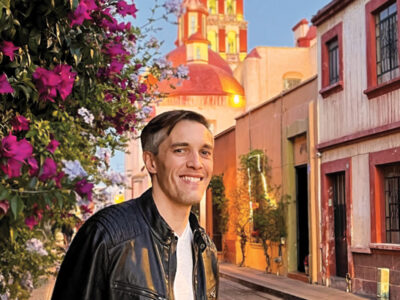

Given that the 29-year-old Perlmutter was a Google executive with the grandiose title Head of Cuba Strategy & Operations, it might seem surprising that he didn’t know that shout-out was coming. But since he was in the residential neighborhood of Miramar, and had no access to the internet or television, he was taken by surprise.

“I had the president of the United States, the leader of the free world, speaking to my project, which was quite amazing—and I had no idea,” he remembers.

It was also a little strange to be recognized publicly, since Perlmutter had long been doing his work under the radar. For more than three years, he had been leveraging Google’s considerable influence to get Cubans online. That involved engaging in a series of internal lobbying efforts, a discreet fact-finding mission to the island nation with CEO Eric Schmidt, and conducting high-level negotiations with the Castro government. Before Obama restored diplomatic relations, Perlmutter found a way, along with his team, to release free versions of Google products like Chrome, Google Play for FreeApps, and a non-paid version of Google Analytics on the island. After telecommunications-related commerce became legal for Americans, he focused on bigger projects, like winning Google a deal to establish technology hubs across the island.

Though Obama’s visit—the first time a sitting US president had stepped foot on the island in almost 90 years—represented a mark of the two countries’ renewed relationship, his repeated insistence that the Cuban people need free access to the internet was both a sign of hope and a potential stumbling block. The Castro government runs the telecommunications industry, and has made it notoriously hard for its citizens to get online. In the summer of 2014, only 3 to 5 percent of the population had access to the internet. Until recently, aside from select academic institutions and workplaces also controlled by the government, the only places offering connectivity were hotels and “navigation rooms”—which charged the equivalent of $6 to $12 per hour, a fee beyond the reach of everyday Cubans.

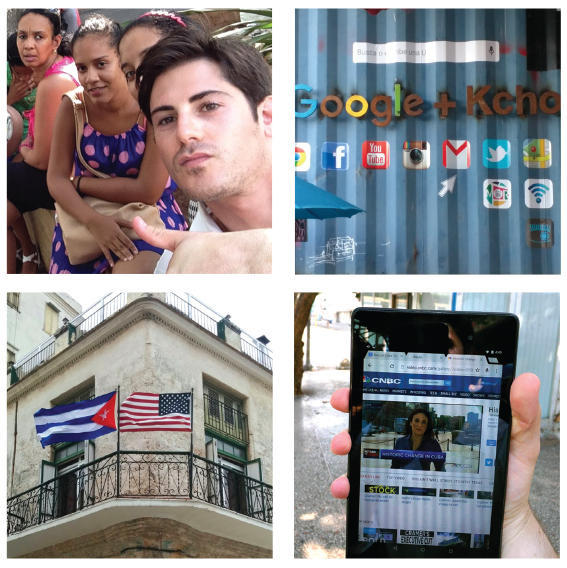

On March 21, the same day Google received a shout-out from the president, Perlmutter cut the ribbon on a free internet center for Cubans in a complex built and designed by Cuban artist Alexis Leiva Machado, better known as Kcho, who filled it with Cuban and American flags, a spiral staircase decorated with books (representing knowledge), and a ceiling painted with clouds—a literal representation of Cloud-based computing.

But the real attraction, provided by Google, was technology—of a kind that had never been seen in that country. Not only was there high-speed internet, 70 times faster than the dial-up speed previously available; there were Chromebooks, Cardboards (the company’s virtual-reality goggles), Android devices—even a set where participants conducted the first ever YouTube livestream from Cuba. While parents in America can’t wait for their kids to put down electronic devices, these parents were overjoyed. One father, crying while watching his teenage daughter use YouTube, pulled Perlmutter aside and said, “You don’t know how much this will change her life.”

“We want to show the world what happens when you combine Cuban creative energy with technology that’s first in class,” Perlmutter told the Associated Press during a tour.

While this center was a small step for Google, it represented serious progress in the effort to open up Cuban society.

Perlmutter “has taken Google from a position of suspicion and anxiety within the Cuban government to a position of a working partnership,” says James Williams, president of Engage Cuba, a coalition of private companies and organizations working to end the travel and trade embargo with the island nation. “It is a really big deal in the sense that the Cuban government has historically been extremely cautious of a US telecommunications company coming in, so to have something tangible there that is branded is a big step forward.”

If Google’s presence has raised some questions about the appropriate role and influence of a telecom firm in a repressive society, the fact that a US company was displaying its logo on Cuban soil represents a giant step for capitalism in one of the last bastions of communism. As the headline of a story in the technology website Gizmodo put it: “Silicon Valley Has Officially Invaded Cuba.”

Perlmutter’s professional life has been shaped by two passions: Latin American culture, and policy and economics. His current role, he figures, simply bridges the two.

The former came from his mother’s family, who lived in Las Cruces, a city of 100,000 people in southern New Mexico. Perlmutter grew up in Denver but enjoyed visits to his grandfather, who lived in an adobe house in the desert outside the city. His mother encouraged his interest by taking him on such horizon-expanding trips as one to the Yucatan peninsula, where they stayed with an indigenous Mayan community.

“I think because it was always in the background, I was always interested in it,” he says of his love affair with Latin America. His fluency in Spanish was such that he was able to take language courses at a local college while still in high school in order to keep improving.

It was also at his high school, Kent Denver School, that Perlmutter’s interest in economics began to manifest itself. He served as president of its credit union, which was the largest student-run bank in the country, with $4 million in assets available for financing new cars and prom dresses (to be safe, parents had to co-sign for loans). He also helped Suze Orman, the CNBC finance guru, research and edit The Money Book for the Young, Fabulous & Broke.

When it came time to think about colleges, Perlmutter found himself increasingly drawn to a certain university founded by a certain theorist, author, diplomat, inventor, scientist, mathematician, freemason, and postmaster. He remembers reading quotes by Benjamin Franklin in Penn’s admissions package and thinking, “This place is perfect.” On arriving as a freshman Benjamin Franklin Scholar in 2005, “I was completely overwhelmed by the amount of things I could do,” he says. “I just remember highlighting 50 courses when figuring out what I would take my first semester.”

He settled on a double-major—Latin American studies and international relations—and wrote two theses. One was a look at agricultural exports on the southern coast of Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay. The second was a comparison between Argentine short-story writer Jorge Luis Borges and Roberto Bolaño, his postmodern counterpart. He received the Hispanic studies departmental award for best Spanish thesis.

“I got totally obsessed with both,” Perlmutter says. “The funny part of this was, everything I did academically, I felt like I was doing in off hours.” After all, he did have a day job from sophomore year on—serving as president of his class, which sucked up as many as 12 hours a day.

“A lot of students on campus don’t even know who their president is and aren’t influenced by them, but Brett could walk down Locust Walk and know everybody,” says Elise Betz, executive director of alumni relations. “When I sat down at the table with the administration and said, ‘Brett Perlmutter is president of his class, and he can mobilize the seniors,’ they responded, ‘Yeah, we know Brett. He can do it.’”

This wasn’t just a hypothetical situation. According to Betz, Perlmutter was, more than anyone, responsible for saving the tradition of Hey Day. In the years leading up to his senior year, the ritual had gotten out of control, with some seniors throwing raw fish, ketchup, flour—even urine, shot from a super soaker—on juniors as they marched down Locust Walk. In 2008 two students were seriously injured, and the University decided that if the situation didn’t change dramatically, Hey Day would either be cancelled or moved to the first day of the seniors’ fall semester.

Perlmutter, along with a committee that included Betz, the Division of Public Safety’s Maureen Rush, Wendy White from the General Counsel’s office, and Rodney Robinson from the Office of Student Life, devised and executed a plan to hold a simultaneous event for his senior class that would distract potential ruffians bent on harassing their rising counterparts.

“Brett, from day one, embraced this,” says Betz. “He said, ‘This is going to be our class’s legacy.’” A new tradition called the Final Toast was created, in which seniors gathered on College Green to eat, drink, and be merry. Every detail—from the timing of the mug giveaway to the signing of a pledge to get into the event—was designed to keep the two classes away from each other.

“We had one year to get it right and Brett was just this movie star,” says Betz. “Honestly, not every [class] president could have pulled it off.”

Asked which he is most proud of, saving Hey Day or bringing Google to Cuba, Perlmutter reflects for a moment, then says: “Helping people live their lives better is what is really important to me.”

After graduating from Penn in 2009, Perlmutter headed to the United Kingdom to continue his studies at the University of Cambridge, having made a commitment to himself that he would spend his days reading and in libraries. Next stop was supposed to be McKinsey & Co., the global management-consulting firm.

“I was looking forward to getting back to the pace of the private sector and something that was results-focused and measurable and impactful,” he says. Then he found out about google.org, a department of Google whose mission was to create products that would help the world. He immediately called the recruiter, who had been reaching out to him for other posts within the company.

One of his first assignments after starting in September 2012 was Constitute, a project that would digitize the world’s constitutions and make them easily searchable by phrases or topics. The idea was that when a nation’s leaders need to write a new constitution or update their existing one, they could use Constitute as a reference.

“From the US perspective it seems strange to think about doing this, because we’ve only written a constitution once in 217 years,” explains Zachary Elkins, an associate professor of government at the University of Texas-Austin, who worked with Perlmutter on the project. “But the rest of the world is updating or replacing their constitutions much more frequently than you would think.” The average lifespan of a constitution is 19 years, he says, and at any given time there are four or five being replaced and numerous others under revision.

Perlmutter saw the project through to fruition and expanded it, says Elkins. In the wake of the Arab Spring it was translated into Arabic; activists in Chile and Brazil have used it in considering new alternatives to their constitutions. Perlmutter also pushed to open a World Constitutions Exhibit and a Constitution Drafting Room (equipped with Constitute) at Philadelphia’s National Constitution Center, and came to the exhibit’s opening in February 2015.

Then, thanks to a Google policy that allows employees to pursue passion projects, Perlmutter started researching how people in countries with limited internet access actually use the internet.

“You’re almost like an ethnographer doing these studies of users,” he says. The most fascinating examples turned out to be in Cuba, where people had developed elaborate methods of gaining access.

One example was entrepreneurs making and selling something called El Paquete Semanal (The Weekly Package), which consisted of hard disks loaded with popular content from around the internet. In addition to music, movies, and so forth, these bundles included Tinder-esque products that were basically PDFs of people’s faces and phone numbers. Other Cuban Millennials were tweeting by sending their messages to a SMS (short message service) number outside the country. Some, lacking access to the open-source code that programmers around the world use, were even making apps by writing their own operating system. Henken tells the story of Yoani Sanchez, a now-famous dissident blogger who wrote posts on her laptop, took pictures of the documents, then—after sneaking into hotels as a tourist—sent them to relatives or friends overseas. Her accomplices would re-type the posts and place them online, since the hourly fee made it too expensive for Sanchez to retype them herself or even upload files to the internet.

After all his research, Perlmutter says he was “shocked that Google wasn’t doing anything.” Here was a country just 90 miles from the US where people were so desperate for the internet that they would go to extraordinary lengths to access and use it. And if they were this successful offline, what could they create and achieve if they were online? As a result of his investigations and his cogitations, he says: “I made the business case internally that if everything in Google is driven by the users, we should be very interested in what these users were doing in Cuba.”

On June 29, 2014, Eric Schmidt announced on his Google+ page that he and three colleagues had just traveled to Havana on a business visa “with the goal of promoting a free and open internet.” The announcement, to use an Old Media phrase, made headlines around the world.

One of Schmidt’s three colleagues on that trip was Perlmutter, who had labored for eight months to make it happen. Because of US sanctions against Cuba, they had to jump through a series of bureaucratic hoops to secure a special license to travel. On the Cuban side, he had to negotiate with a department within the government’s foreign ministry, hosted under the auspices of the Swiss Embassy.

“I explained we were different than the US government—we were a private company, and we were interested in seeing their computer-science companies,” recalls Perlmutter. He also stressed the stakes. “This was a country that was completely cut off, so when you have a luminary like Eric going, that’s how things happen.”

Schmidt and Perlmutter had once been in the same place before—Franklin Field, when the former had been the Commencement speaker at the latter’s graduation. But this trip put them in much closer quarters. With Perlmutter navigating, they met with both governmental and non-governmental leaders, people using the internet and people wanting access to it.

There were two main takeaways for the Google team. One was how low the internet usage there really was: just 3 to 5 percent of the population had any sort of access to the Web. Then there was the political component: the US embargo of Cuba, not the Cuban people, played the biggest role in this disconnect.

As soon as he arrived back in the States, Schmidt called for an end to the embargo. “As US firms cannot operate in Cuba, their internet is more shaped by Cuban narrow interests than by global and open platforms,” he said. Then, Perlmutter recalls, he turned and said: “Brett, your job is to launch as much Google [there] as you can.”

Google Play launched two months later. Google Analytics and Chrome followed before the end of the year.

On December 17, 2014, President Obama announced the normalization of relations between the US and Cuba. While Google insists it had nothing to do with it, Henken believes that trip likely played a role.

“I don’t think it came from Google,” he says, “but there was a synergy that was obvious, and Google made it more palatable by making that trip and making that declaration.”

Whatever the backstory, the announcement certainly was good news for the tech giant. With it came a policy change that allowed telecom companies to do business in Cuba for the first time in 54 years.

“We found ourselves in this amazing position where we were in Cuba because we launched the projects; there was a hole in the embargo for telecom infrastructure projects; we had already worked with the Cuban government; and we have teams that work on connectivity initiatives within Google,” says Perlmutter. In other words, while other companies were starting from scratch, Google was already on the ground, running.

“There is very much a dearth of information on telecommunication infrastructure in Cuba,” says Williams. “Brett is the most knowledgeable person—probably in the world, but at least in the United States—about it.”

Perlmutter gave up his other responsibilities at Google and began focusing on Cuba full-time. He started traveling to the country so often to negotiate deals that he acquired a Cuban cell phone. So far, apart from the internet center, nothing concrete has been announced, but he is willing to hint at the company’s aspirations.

Most obviously Google is trying to help the Cuban government create a viable plan to get many more people online. Because Cuba is so behind and so geographically compact—and because the technology today is so much better and cheaper than it was when people in other countries were starting to go online—Cuba can skip most of the steps that other countries have had to take and put everyone on wireless immediately.

“Cuba is really well positioned to go from zero to one like almost no one country can do,” Perlmutter explains. “It could potentially connect all of its citizens in a year or two.” Given that some places in the US still use copper wires, he notes, “it would take the US 25 to 30 years.”

The obvious upside for Google is that when more people use the internet, it makes more money. In addition to the online ads, the company makes money by moving the data that go in and out of the equipment of internet service providers. So while TimeWarner may provide your actual internet, Google provides what’s called the transit, which brings you content. The larger the data flow, the more money Google makes.

Some projects are more altruistic. The company is exploring creating high-altitude platforms or aircraft that can provide connectivity during natural disasters.

“Cuba gets a lot of hurricanes, for instance,” Perlmutter notes. “If someone can get 10 Mbps [megabits per second] on their cell phone in a hurricane, that could really save lives.” They also want to build more internet centers like the one they launched in March.

Tim Ashby, a London-based consultant and legal advisor to companies pursuing commercial opportunities in Cuba, believes Google will eventually use Cuba as a technology hub for other parts of Latin America and the Caribbean. He points out that the country has a large number of highly trained software engineers, and since US companies are now legally allowed to train employees there, “Cubans would like that.”

Perlmutter agrees that Cuba has “huge talent capital.” Henken says he has heard rumors of Google cars mapping the island and its digital team creating an online national archive that would enable Cuba to highlight its cultural heritage.

No one knows just what will happen in the next five years, says Williams. “It will take a long time no matter what you are doing. It’s not like the Cubans are going to change overnight. There is a tension there that is going to make things move slow.” And in its efforts to speed up the process, Google will unquestionably face challenges.

The first is to what extent it should get into bed with the Cuban government. It’s well documented that when Google was first exploring Cuba, it met with state dissidents and bloggers. Sanchez was a guest at Google Ideas Conference in October 2013, and the YouTube video of her performance is still being watched. These days, though, Google refrains from speaking about any rebels and isn’t working with them at the moment.

“It looks suspiciously like Google has thrown the activists under the bus,” says Henken. “One of the downsides to this is, What are they agreeing to? What concessions, exceptions, or laws are they forced to agree to to do business in Cuba?”

In Williams’ view, though, Google is just doing what it needs to do to help the wider public. “If you work on major projects in this area, you are going to have to work with them and find a way to do that,” he says. “I think Google’s perspective is that expanding internet access for the everyday Cuban is worth it.”

Just how worthwhile it will be for Google is another question. Cuba has already chosen to work with Chinese firms rather than American ones. The new wireless hotspots, for example, are equipped by Chinese telecom giant Huawei.

“Most of what they are already using is Chinese, not American and not Google,” says Henken. “Google would love to be the ones to do it, but that’s impossible or a long way off, because Google is an American company and Google’s values are at odds with the Cuban government.”

But the company may not even be in the game to get big deals and make a lot of money. With a relatively poor population of just over 11 million people, Cuba is not exactly a “top-tier business priority,” says Williams. “It’s more of a curiosity and something they would like to do, but they aren’t going to put their top executives all-time on it.”

Henken agrees that their efforts are “probably first about the principle, and second about public relations.” Which might just explain why they chose Perlmutter to handle operations.

“He’s a poster child for Silicon Valley optimism,” Henken says, “and he represents the best of that dream and that image that Silicon Valley, Mountain View, and Google project.”

If Google’s Head of Cuba Strategy & Operations needed any reassurance about the significance of his technology center and his overall efforts, he got it when he picked up a copy of The Miami Herald for his flight back to the States in March. Above the fold was a picture of Obama in Cuba. Below it was a photo of himself and Kcho, the Cuban artist.

“That,” he says, “is when I truly got a sense of ‘Wow, we really accomplished something.’”

Alyson Krueger C’07 is a freelance writer and frequent contributor to the Gazette.