An unexpected journey from ghost writer to stand-in mom.

By Susan Orlins

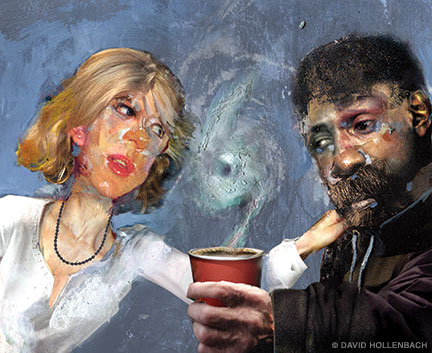

He’s a middle-aged black man. I’m an older white woman.

He spent most of his life in prison. I once got caught by a traffic camera.

He’s addicted to crack. I’m addicted to popcorn.

He rescued Katrina victims. I rescued a beagle.

October 2013. A large, dark-skinned man in a black hoodie and worn-out running shoes hunches over a scrap of paper. It’s my first day as a volunteer editor at Street Sense, a Washington newspaper written and sold by homeless vendors.

His name is Gerald Anderson and he is a Katrina survivor. For the upcoming issue, he’s writing to thank his newspaper customers, who pooled airline miles to send him back to New Orleans—his first visit since his evacuation after the hurricane.

Gerald stopped going to school after seventh grade. Although he learned to read and write in prison, he likes having me ask questions and then write on my laptop for his article.

I ask why he didn’t move back to New Orleans. “It will never be the same,” he says. “When I left after Katrina, it was like being released from prison. I loved visiting my family, but it feels good returning to DC, where my Street Sense customers are family to me.”

Gerald has been in and out of prison all of his adult life. The first time he shared a roof with his father was at age 25, in Louisiana State Penitentiary. The last time he spoke to his mother was from jail. She told him, “I’m glad you’re in prison, rather than lying dead somewhere.”

For six months after his latest prison release, Gerald lived in transitional housing. Now he spends nights on the street, avoiding the violence, drugs, theft, bathroom sex, and bedbugs he encountered in shelters.

Gerald has big stories about prison, and about rescuing Katrina victims. He also has a flair for putting words together, which—combined with his cadence and Southern black dialect—becomes a storytelling performance I would pay to see.

“Let’s write a series for the paper about Katrina and your time in prison,” I propose. Gerald is looking for someone to help tell his story, and suddenly I am looking for a story to tell. But he isn’t ready to trust me.

Until I met Gerald, the subject that most absorbed me was me. Every day I sat at my computer, crafting myself into a character for my blog, with posts ranging from the daily challenge of which underwear to wear to the annual challenge of vacations with my ex and our daughters. After publishing a memoir in 2013, I looked up and noticed how alone I was. Now, for the first time, I want to write about someone else. After more nagging, Gerald finally agrees to meet.

January 2014. We meet at Starbucks, I open my laptop, and Gerald begins talking about his early life: My brother would pick me up, hold me to the ceiling, and drop me. Like a bee sting, it hurt for a minute and then it went away. After a while nothing hurt.

Over the next 18 months, we meet every week, often on Saturday afternoons; weekends no longer feel lonely. Regardless of what I ask, Gerald answers.

Were you ever raped in prison? “I never got tried that way. I knew the rules from being in the street.”

Did you ever murder anyone? “I was arrested, but not convicted, for negligent homicide after being in a stolen car with my friend, who hit a woman that died.”

Gerald speaks so fluently that I don’t question the veracity of what he says. Frequently he interjects, “It puts chills in my body, like it’s happening now.” His Katrina timeline doesn’t match precisely with what I find online, but memoir is how you remember your past, not an exact depiction.

Yet, just to check on something he told me, I Google “Gerald Anderson heroin.” A 2009 FBI report confirms Gerald’s last incarceration.

Gradually we fall into a rhythm. He dictates his story, pausing while I tap out his words, as though I’m his secretary in some screwball comedy. Without the romance. Rather, ours is a friendship, in part a mother-son dynamic with the accompanying joy and angst. On the day a filmmaker shoots a trailer for the book we plan to publish, based on his Katrina articles, Gerald and I ham it up. And then as I’m leaving, I turn back and call out, “Don’t go out tonight. You’re too tired.”

He gives me a look and I immediately regret my admonition. Later he phones to say he’s sorry for acting annoyed. He’s always the one to call first. He won’t let a squabble linger.

Months pass and we spend more and more of our visits talking about our present lives. But there’s a disparity in how much we learn about each other. Gerald talks about his interest in this woman or that; his ire about paying $300 to sleep on the floor of an acquaintance who then locked him out and stole his clothes; his grief for two brothers and a nephew, all of whom died in the past year. There is also a disparity in our skills for navigating the world—stuff like finding a locksmith when his scooter lock jams—for which Gerald frequently turns to me. That said, for someone who spent most of his life behind bars, he possesses remarkable personal resources, such as the way he diffuses stress by talking out problems.

All the tumult in his life barely allows time to discuss my woes, though I do tell Gerald about an emotionally vacant beau, whom he advises me to cut loose. At my birthday celebration, Gerald meets my three daughters. Ever after, he’ll ask, “How’s the lawyer?” “How’s the teacher?” “How’s the Chinese one?”

Whenever Gerald and I get together, I buy lunch. Once he asked me for a loan, which he paid back. Yet for all my gushing about our friendship, I have never invited Gerald to my home, located in a neighborhood with manicured lawns. I feel self-conscious about my abundance compared to his struggle to get by.

May 2014. A courtroom rail separates Gerald and me. He hangs his head before a judge, who is deciding what to do about two failed urine tests. He admits to using crack, a parole violation. The judge holds up 22 letters of support from Gerald’s newspaper customers and sentences him to residential drug treatment.

Some friends attract me because they are cerebral, others because they are upbeat and fun. And then there are those like Gerald, whose problems give me a rush. Gerald’s rehab sentence catapults me into high-intensity fixer mode, starting with finding a place to store his scooter, which is always breaking down.

“My scooter is my wife,” he reminds me. I can relate, because I feel the same attachment for the bicycle I’ll be pedaling 12 miles every Sunday—visiting day at rehab—for the next few months.

April 2015. Gerald has been substance-free for nearly a year and now lives in a recovery home with nine other men. He reappears before the judge, who dismisses all charges. He tells her, “Thank you, Judge, for giving me a second chance.”

His pride is palpable when she says, “I follow your story in Street Sense. Let me know when your book comes out.”

April blurs into July. Finally I finish editing and receive proof copies of the book. The first thing Gerald wants to do is sign one for the judge.

After giving her a copy, Gerald dictates to me for a Street Sense article. “I never thought this would happen. The judge shook my hand and then we sat at the same table where I sat when she sentenced me, and we’re talking and telling stories like we’re in a coffee shop.”

July 2015. Still Standing: How an Ex-Con Found Salvation in the Floodwaters of New Orleans is published. Two days later, Gerald pulls out a wad of $20 bills from sales to his “family” of newspaper customers. He plans to buy a new scooter—but wants me to hold most of his earnings. “I’m an addict,” he says. “I don’t want to have too much cash.”

I’m about to go out of town for two weeks, and I don’t want all that money tempting him into a drug purchase. So I wait with my hand out while he peels off bills, $1,300 dollars in all.

Empty-handed, Gerald stands there, his expression a mix of bewilderment and resentment. The unsettling thought occurs to me that I’ve just placed the scooter of his dreams into my fanny pack, but I rationalize he’ll make more tomorrow.

Later, Gerald’s roommate emails me to say how upset Gerald is that I took all the money. He intended to buy his scooter while I’m away.

For a recovering drug addict, stress can be as risky as too much money. I phone and text Gerald—and for the first time ever, he doesn’t respond. All night I worry the book will cause Gerald to relapse, as well as damage our relationship. I phone him as soon as my alarm goes off.

“I’m soooo sorry,” I tell him. “Just tell me how much money to bring you. I want you to get a decent scooter.” On my way out of town, I stop by the Metro where he sells his papers to drop off a thousand dollars. I hug him good-bye, relieved.

A few weeks later we’re munching on chicken wings from his favorite place. We’re working on his serial about life after Katrina for Street Sense, which he’s counting on me to eventually edit and publish as his second book.

“I gotta tell you what happened this morning,” Gerald says. I lean forward, eager as a kid awaiting an ice-cream cone.

Susan Fishman Orlins CW’67 is an award-winning journalist and co-author of Still Standing: How an Ex-Con Found Salvation in the Floodwaters of New Orleans, available at Amazon. Her previous book was Confessions of a Worrywart: Husbands, Mothers, Lovers, and Others.