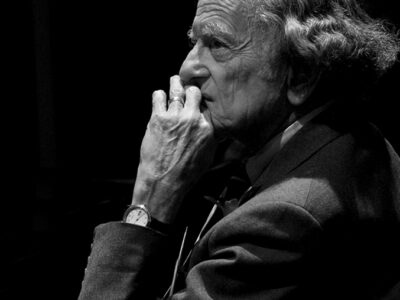

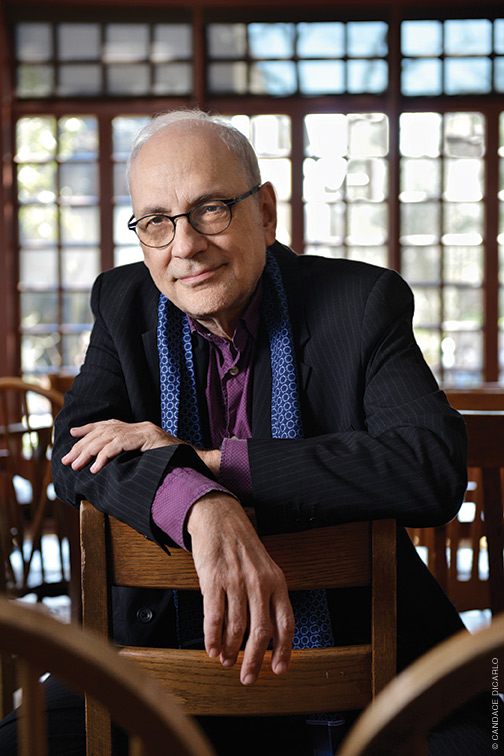

The Penn poet and professor has won the prestigious Bollingen Prize for his (self-described) “controversial and disliked” work.

In 1949, the first Bollingen Prize for Poetry went to Penn alumnus Ezra Pound C1905 G1906 (a story in itself, for which see this issue’s “Old Penn.”—Ed.). Seventy years later, another Penn poet is the winner: Charles Bernstein, a prolific writer and much admired teacher whose online CV was already 97 pages long.

The Bollingen, given biennially by Yale University, is probably the most prestigious prize in American poetry—and, with an award of $165,000, among the most lucrative. The judges cited both Bernstein’s “decades-long commitment to the community of arts and letters,” as well as “his extraordinary new collection of poems, Near/Miss,” published last year by University of Chicago Press. The poet told the Daily Pennsylvanian that he was grateful but surprised to receive the Bollingen, because his work “remains controversial and disliked by a lot of people who give out awards in the mainstream of culture.”

Over the course of his long career, Bernstein has been an important figure in what’s known as Language poetry, which shuns the traditional poetic sensibility in favor of a skeptical emphasis on the ambiguities of language. Bernstein’s poetry, often antic and frequently political, relies in particular on the materials of popular culture.

“Early Bernstein can be opaque, annoying those who see difficulty as elitist and who want poetry to be cuddly and educational,” Daisy Fried wrote in the New York Times in 2010. “But everyone should love the later Bernstein, a writer who is accessible, enormously witty, often joyful—and even more evilly subversive.”

Bernstein, the Donald T. Regan Professor of English and Comparative Literature, had been teaching at Penn since 2003. But the 68-year-old New York native retired at the end of the spring semester. Gazette contributor Daniel Akst C’78 asked him about his work, his plans, and poetry at Penn.

You’ve defended difficulty in poetry. Yet the first poem in Near/Miss can be read as a caustic attack on the vanity and condescension of obscurantist poems. Is it mocking the self-importance of poets who speak only in tongues? Or does it skewer readers who look at modern poems and see only your opening lines: “This is a totally inaccessible poem. Each word, phrase & line has been designed to puzzle you, its reader, & to test whether you’re intellectual enough,” et cetera?

Whatever I think, I like to think the reverse too. That’s my aesthetic: Three sides to every coin or Bob’s your uncle. There is a companion poem to the opening work in Near/Miss—the one you quote that starts with a comic proclamation of incomprehensibility. That twin poem, in my book Girly Man, starts with an equally comic proclamation of accessibility.

My explorations and modeling of difficulty and accessibility allow for reflections on the difficulties and ease of negotiating everyday life. I have found life more difficult than easy, which makes for elegy more than celebration in my work; in any case, the two go together. Much of the resistance to difficulty in poetry is related to the experience of confronting the unfamiliar, which is unwelcome to those who prefer comfort to challenge. My sense is that we all get fed too much of the familiar in conventional literature, journalism, and entertainment. The kind of poetry I want offers something different—not necessarily better. Poetry is an art form that is largely outside mass culture and does well when it offers an alternative to the legibilities of mass culture.

It turns out that the somewhat nutty speaker of the first poem in Near/Miss really wants to be understood but flaunts inaccessibility as a self-protecting shield, the way a lover says, “I don’t care if you love me,” meaning “that is all I care about.” Much conventional lyric poetry tells you what the poet feels—with the idea that readers can share that feeling. In contrast, I want a poetry that doesn’t tell me how or what to feel but gives me a place to feel. Which means that ambiguity, ambivalence, and dark thoughts—which is to say, difficult feelings—abound.

In a lot of your poetry you seem concerned with challenging what we might call automatic language—not just idiom, but the kind of cliché and cant that is so common it forms a kind of atmosphere. Why do you choose to make art from it?

It’s both a challenge and a celebration. I love clichés but love them as clichés, so I often accentuate their iconic qualities, exaggerate them, deform them. At a Russian translation seminar hosted by my colleague Kevin Platt, we were talking about how to translate a phrase of mine, “slashes in the pan” and it took me a while to remember “flashes in the pan”—because I thought of “lashes in the pan” (and lashes/flashes of pain) and “ashes in the pan.” By “slashes in the pan” I was suggesting transient marks, like writing on the wall, but why not “writhing” on the wall or “writing on the fall,” if that is not too Biblical? I call this “echopoetics.”

There’s a lot of sly humor and wised-up subversiveness in your poetry. Pop lingo is yoked to vast learning, and my sense is that the Jews appear with greater frequency than chance would dictate. Do you think your work is distinctively Jewish in style and outlook?

Jewish comedy is fundamental to my work, in particular the Marx Brothers, George Burns, Henny Youngman, Sid Caesar, and Lenny Bruce, to mention just those I have quoted or written about. In more recent times, I’ve felt a great affinity with Mel Brooks, Jackie Mason, Joan Rivers, and Larry David. My poems and essays have as many Jewish jokes as puns—and also many Jewish jokes that are puns. But the Jewishness in my work is not religious, it’s cultural and ethnic, and it touches on the diasporic. My grandparents came to America in the late 19th century from the Pale of Settlement, and I grew up in the distinctly Jewish world of the Upper West Side of Manhattan. I feel a strong connection to left Yiddishkeit culture and to the lost world of European Jewish artists and intellectuals, such as Walter Benjamin, about whom I wrote an opera, Shadowtime.

But I wouldn’t put any of this over and above other quite different affinities, allegiances, and affiliations. Indeed, my identity is turbulent and plural, filled with contradictions and preternatural connections. I am nothing if not rooted in (and uprooted by) the cosmopolitan, with equal parts borrowed, invented, and inherited—all of which I explore, sometimes comically, sometimes tragically, in my work.

I was fortunate to study poetry with the late Dan Hoffman. He’d ask us to do translations to help us understand the mechanics of a poem, the trade-offs between sound and sense, the need for precision, etc. You’ve done quite a bit of translating. How has that influenced your own poems?

All poetry’s translation—or ought to be! There are no originals for my poems, just endless variations of versions. Translations require transformation. In my books, I use translation as a way of including other voices, channeling particular works that seem extensions of whatever I am most caught up in, so those translations become my own poems. The common saying is that poetry can’t be translated—that poetry is what is lost in translation. I prefer to say, poetry is what is found in translation: that which can’t be translated is not poetry. In saying that, I am not discounting the significance of the differences between the original and the translation. But the poetry—the art—of translation is what you make with those incommensurabilities. Poetry is the art of differences.

You’ve announced your retirement. Has your Penn experience shaped your work in any particular way?

I started to teach when I was around 40, so it’s been a 30-year run. I have taught 40 doctoral seminars, directed 45 PhD dissertations, and been on another 25 doctoral committees. Working with these 70 graduate students has been an immersive and exhilarating experience. I could not have been luckier than to have had the chance to learn from each one of these young scholars (many of whom were also poets). And it’s also been a pleasure to be able to talk about poetry every week with undergraduates—and to pick the poems we discuss, too. I have read a detailed response for each week’s reading from every one of the active students in my classes since starting—and not given a single exam. So for me teaching has been an intensely personal experience, an experience primarily of listening. I’ve loved it.

What comes next?

I am ready to unplug from all that while continuing my other work—and with such ongoing projects as PennSound, the immense poetry recording archive I founded with [Kelly Professor of English] Al Filreis. If I have a plan it is to try to do less—even nothing from time to time.

Most Penn alumni probably don’t read much poetry, even if they read lots when they were in college. Could you suggest a book or three that might help them rediscover the splendors of the form?

I doubt most Penn alumni read much poetry when they were at college! It’s okay. Poetry is not a moral obligation and it does you no good anyway, or as much bad as good. The worst thing for poetry is to have it seem like it’s good for you, like spinach or castor oil. But I’d say, go to PennSound and listen to readings by poets whose names you know as well as by those you’ve never heard of. Listening is a good way to attune yourself to poems. (An audio version of Near/Miss is at Amazon.) And then take Al Filreis’ online poetry class, Modern and Contemporary Poetry [“The ModPo Squad,” Sep|Oct 2017].

Daniel Akst C’78, is a writer in New York’s Hudson Valley.