The US government is a bloated, dysfunctional Leviathan, and the only way to fix it is by hiring a million more federal bureaucrats.

The US government is a bloated, dysfunctional Leviathan, and the only way to fix it is by hiring a million more federal bureaucrats.

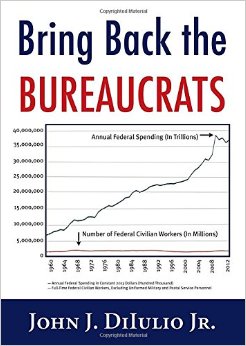

That’s the latest argument from John DiIulio, the Frederic Fox Leadership Professor of Politics, Religion, and Civil Society. DiIulio is no stranger to provocative policy ideas. He ran George W. Bush’s Faith-Based Initiative in the 2000s. His new book exemplifies his knack for intellectual attention-getting. He all but invites readers to judge it by its cover, which features a graph contrasting the 50-year quintupling of annual federal spending against the stagnant number of civilian government workers tasked with overseeing it, under the title Bring Back The Bureaucrats.

Fears of a federal “Leviathan” are, of course, as old as the republic. But DiIulio contends that something even scarier has emerged since Goldwater and Reagan revived anxieties articulated by Jefferson and Thoreau before them: “Leviathan by Proxy.”

Since the 1960s, DiIulio observes, the American public has sent two messages to their representatives in Washington: they “hate ‘big government,’ but they love, love, love federal government goods, services, and benefits, such as a large national defense establishment and total health care coverage for grandparents in private nursing homes.”

Congress has indulged both wishes, steadily increasing government’s scope while preventing the growth of the government itself.

This accomplishment rests on two sleights of hand.

“America’s big government works by borrowing billions of dollars each year from Americans who are not yet born and hiring millions of Americans each year who are never counted on the federal payroll,” DiIulio writes.

In place of bureaucrats, the government has essentially outsourced administrative responsibility to a wide range of surrogates in the public and private sectors.

State and local governments have increasingly become federal subcontractors, managing programs such as Medicaid and using federal block grants to address Congressionally determined priorities. Collectively, their payrolls have roughly tripled over the last 50 years. For-profit business proxies now receive upwards of $500 billion in contracts to carry out government-mandated activities. In 2012, DiIulio observes, the Department of Defense alone “awarded more than 100,000 single-bidder contracts and task orders worth, all told, more than $150 billion, much of it going to DOD-dependent ‘defense companies’ that rely on Washington for most of their annual revenues.”

And what DiIulio dubs the “entitlement-nonprofit complex” functions as something approaching a shadow welfare state. “In 2012,” he reports, “governments entered into about 350,000 contracts and grants with about 56,000 nonprofit organizations (an average of six contracts/grants per nonprofit organization) and paid $137 billion to nonprofit organizations for services” ranging from hunger relief to economic development schemes.

Restraining government’s growth while expanding the promises it makes has been a lucrative strategy for sitting Democrats and Republicans alike. From 1964 to 2012, he notes, “Federal government incumbents in both parties have placated the voting public and won 25 consecutive national plebiscites.”

But the public pays a big price, he argues, not only in the poor results that stem from fragmented accountability and twisted implementation chains, but in the tendency of outsourcing to beget ever greater expenditures.

“In Leviathan by Proxy, federal civil servants function mainly as grant monitors or contract compliance officers, but the bureaucrats are not the proxies’ bosses,” DiIulio writes, drawing on the scholarship of Donald Kettl, former director of Penn’s Fels Institute of Government. “Rather, each proxy sector—state and local governments, for-profit businesses, and nonprofit organizations—has a highly active interest group presence in Washington” that influences federal policy for its own benefit.

His solution: hire one million more full-time civil servants by 2035. “More federal bureaucrats, less big government,” he posits. The corollary, he suggests, is: “more direct public administration, better government.”

DiIulio offers several examples to support his thesis. One starts with the disastrous response to Hurricane Katrina by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. That, DiIulio asserts, was the natural result of Congress dramatically expanding the agency’s responsibilities after the 9/11 attacks while hamstringing its growth. “In 2004, the year before Katrina, the agency was subject to a congressionally sanctioned hiring freeze on more than 500 open positions,” DiIulio notes.

The silver lining to FEMA’s “spectacular failure” was that Washington correctly diagnosed the underlying problem, in DiIulio’s judgment. Seven years later, when Hurricane Sandy ravaged the New Jersey coast and flooded sections of the New York City subway, FEMA had some 4,800 full-time employees—compared to 2,100 when Katrina hit. “FEMA’s response to Hurricane Sandy was not perfect,” DiIulio says, “but it was near perfect by comparison to its Katrina follies.”

DiIulio points to the IRS as another realm where bureaucrats yield big dividends. He cites a 2012 US Government Accountability Office analysis which concluded that for every dollar the IRS spends on “correspondence exams” involving taxpayers reporting incomes between $220,000 and $1 million, it recovers $25. Yet even as the government fails to collect an estimated $450 billion in taxes annually, Congress has effectively seen to it that the IRS is chronically understaffed.

“Short-staffing the IRS must take the prize as the last half-century’s single most pennywise but pound-foolish federal workforce policy,” DiIulio writes.

As a self-described “pro-life and pro-poor Catholic Democrat,” DiIulio can be pointed on the subject of what motivates Washington to assign some responsibilities to professional civil servants while leaving others to surrogates.

“When we really care about something, we seem less likely to contract it out,” he remarked in an interview with the Gazette. “You know, we don’t contract out Air Force One. It’s Air Force One.”

He added that services for the poor seem more prone to complicated proxy arrangements than services for the middle-class and wealthy, describing the tortuous implementation chain of federally mandated (but not administered) USDA-funded summertime lunches for low-income children, vast numbers of whom go hungry outside the school year as a result.

“Big government in drag dressed as state or local government, private enterprise, or civil society is still big government,” he contends. “Growth in this American ‘state’ is harder to restrain, and its performance ills are harder to diagnose and cure, than they would be in a big government more directly administered by federal bureaucrats.”—T.P.