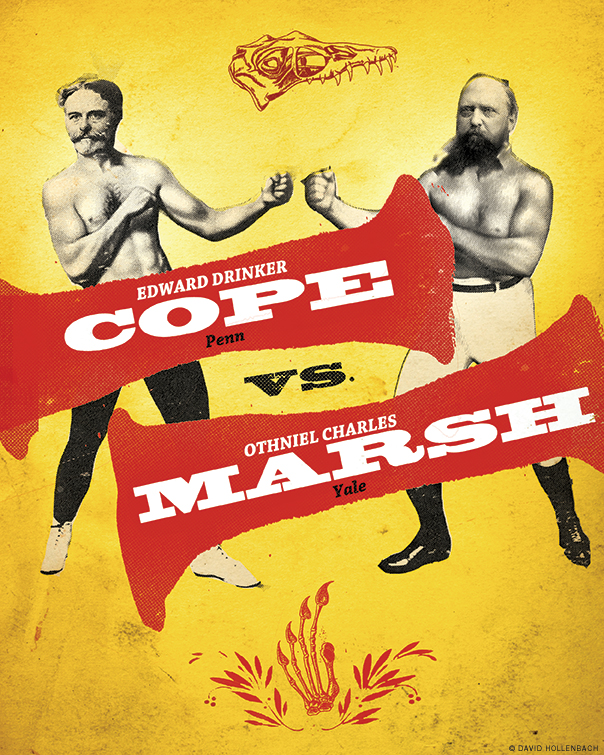

Dinosaur hunter Edward Drinker Cope studied briefly at Penn in his youth and ended his days as a faculty member at the University. In between, the impulsive and driven scholar churned out more than 1,400 scientific publications—and exchanged many harsh words—in an epic battle with his more methodical rival, Othniel Charles Marsh of Yale, for primacy in the nascent field of paleontology.

BY DENNIS DRABELLE | Illustration by David Hollenbach

Hard on the heels of the California Gold Rush and the Comstock Lode Silver Rush came the Great Plains Bone War. At stake in the Bone War were dinosaur fossils, not ore, but what the struggle lacked in glitter it made up for in intensity and vitriol, supplied by two paleontologists locked in bitter rivalry: Othniel Charles Marsh, a longtime professor at Yale, and Edward Drinker Cope, an independent scholar who in his last years taught at Penn. Marsh and Cope’s drawn-out race to unearth, describe, classify, and claim intellectual property rights to dinosaurs was characterized by spying, dirty tricks, turncoats, and mutual accusations in the gutter press. Today dinosaurs are the domesticated stuff of kids’ fantasies; a century-and-a-half ago, the beasts drove grown men to act like children.

Edward Drinker Cope sprang from the Philadelphia establishment: his Quaker father, Alfred, was co-owner of a prosperous shipping firm. Born in 1840, the precocious Edward found himself drawn to the natural sciences in a favorable place and time—Philadelphia was a scientific mecca, newly discovered fossils were adding years by the tens of millions to the Earth’s age, and Darwin was honing his theory of evolution in advance of its release—but Alfred had a different future mapped out for his son: gentleman farmer. Edward attended a Quaker day school and then boarded at Westtown School near West Chester, Pennsylvania. Writing home to his parents, the 12-year-old schoolboy marshaled cunning, charm, and self-knowledge in a way that could hardly have failed to get him what he wanted: “that Quarter dollar is not gone by any means, I only begin to ask soon, as I thought some more might be hard to get … for when a boy is hungry money is nothing, food must be had.”

When in Philadelphia, Cope frequented the Academy of Natural Sciences, becoming such a fixture that by the age of 18 he had a part-time job there. A year later, he racked up his first scholarly publication, and not even his father’s gift of a farm could dissuade the young man from pursuing a scientific career. In either 1860-61 or 1861-62 (the evidence is ambiguous), he attended Penn, where he is known to have studied comparative anatomy with the famous Joseph Leidy M1844, professor of anatomy and founder and head of the Department of Biology at the University. Cope’s formal education ended at this point, though without adverse effect on his progress. To his job at the ANS he added one as a researcher in herpetology at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

His father sent Edward off to the safety of Europe for what proved to be the last two years of the Civil War. The young man used his freedom to immerse himself more deeply in science. It was during this period, Marsh later recalled, that the future combatants first met, in Berlin—and hit it off. At the time, according to Mark Jaffe in his book The Gilded Dinosaur: The Fossil War Between E.D. Cope and O.C. Marsh and the Rise of American Science , Marsh “had two university degrees, but only two published scientific papers. While Cope had no degrees, he had already published thirty-seven scientific papers.”

Back home in 1865, Cope landed a teaching position at Haverford College, a Quaker institution, probably thanks to string-pulling by his dad. In 1866, Edward was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society, whose journal became a favorite venue for his paleontological articles, some of them on an early specialty of his: fossil fish.

The young professor married a distant cousin, Annie Pim; their only child, a daughter, was born in 1866. After Cope gave up his teaching post in 1867, the family moved to Haddonfield, New Jersey, to be near local fossil deposits in which he’d already discovered what was only the second known American dinosaur skeleton (the first had been found by Leidy). Cope’s farm was making money, which his father supplemented with infusions of cash.

Marsh, meanwhile, had joined the faculty of Yale, his alma mater—a tie that strengthened when his rich uncle donated the money for what became Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History. The first hitch in the Cope-Marsh friendship occurred in 1867, when Marsh got his hands on the remains of an ancient aquatic lizard from a New Jersey dig. He named it Mosasaurus copeanus, but the honor failed to assuage Cope’s sense of being scooped in his own backyard.

A year later, Cope made a costly blunder. An army surgeon in Kansas sent the disarticulated skeleton of a “sea serpent” to the ANS. Cope put the creature together literally ass-backwards, giving it an extremely long tail when, in fact, it had had an extremely long neck. When Marsh came to town, Cope invited him to have a look. Marsh noticed the mistake and pointed it out. Cope stood his ground, and Leidy was called in to referee. The story goes that Leidy issued his verdict by silently picking up the head fragment and walking 35 feet to the creature’s other end, where he put the fragment back down. The mistake might have been finessed if Cope, in a hurry to get on the scoreboard again, hadn’t already written up his findings and submitted them to the American Philosophical Society, which had printed and disseminated advance copies. Cope scurried to retrieve these, but a few got away.

Over the years, Marsh kept Cope’s error alive by dragging it into almost every phase of their burgeoning feud—the scholarly equivalent of poking a sore. (Ultimately, however, Marsh made what was arguably a worse mistake: he matched a dinosaur body with the wrong head, thereby bollixing up the taxonomy of two species.)

With the American West opened up by the transcontinental railroad in 1869, Cope and Marsh began making summer forays to the fossil fields of Kansas, Colorado, Montana, Wyoming, and elsewhere, typically as advisers to federal geological surveys. They soon clashed over issues of territory and primacy.

As Keith Thomson explains in The Legacy of the Mastodon: The Golden Age of Fossils in America, by the mid-19th century North America had earned a reputation as “a huge open textbook for the discovery of the geological structure of the earth and its ancient inhabitants.” The book was huge and open, all right, but also divided into far-flung chapters, making fossil-bearing strata coveted workplaces. Even by train, travel to a promising locale was costly and time-consuming, as were preserving, packing, and shipping fossils back East for study. Just as a prospector for gold or silver would call dibs on the area of his strike, so paleontologists developed a first-on-the-scene possessiveness. The difference was that while the miner had recourse to laws that would protect his investment and effort, the scientist did not. If Paleontologist A digs into a hillside and Paleontologist B comes along, what were the ethics? How much clearance was A entitled to? There were no easy answers to such questions.

The methodical Marsh went to work in Kansas and Wyoming but was slow to publish his findings. The speedy Cope felt free to double-check formations his rival had moved on from, and then to rush what he discovered there into print—a habit Marsh viewed as poaching. On one occasion Marsh’s men went so far as to plant a skull and unrelated teeth in a site they were leaving. When Cope came along, he assumed that the skull and teeth had been overlooked, that they went together, and that he’d found a new dinosaur species, which he duly wrote up. Later it came out that he’d been tricked. One of Marsh’s Yale colleagues, James Dwight Dana, called Cope “a man of great learning & ability and were he not in so burning haste would always do splendid work.”

Kansas was also the site of the feud’s ugly nadir. Years after the event, the paleontologist Samuel Williston, who had defected from Marsh’s team to Cope’s, wrote Cope a letter of confession. Marsh had ordered the destruction of certain fossil fields—in one instance by setting off dynamite—to keep Cope from having a go at them, and Williston had carried out one of these orders. “It is necessary for me to say,” he concluded, “I only despised him for it.”

Other colleagues and agents fell out with Marsh, too, sometimes over his hogging of credit, sometimes over his slowness in paying their salaries. But it would be wrong to depict Marsh as an out-and-out knave. Much to his credit, he stood up for the Sioux when they were being cheated by unscrupulous federal Indian agents. While working nearby deposits, Marsh learned of the corruption from Red Cloud himself and promised to bring it up with President Grant. Marsh kept that promise, pressing the case so hard that both the commissioner of Indian affairs and his boss, the secretary of the interior, had to resign.

Alfred Cope died in 1875, leaving Edward roughly a quarter of a million dollars (about $5.4 million today). This allowed him to mount his own expeditions without subordinating himself to government surveyors.

It was at this flush moment that Charles Sternberg came along. As a teenager, Sternberg had explored the badlands of western Kansas, where the family had moved from upstate New York so that the father, a minister, could run a Lutheran college. Charles soon realized he had a gift for reading landscapes and picking out fossils. Ignoring his father’s protests that this was no way to make a living, the young man tried to catch on with Marsh’s 1876 expedition, but the last opening was already filled. As Sternberg recalled in his high-spirited memoir The Life of a Fossil Hunter, he sat down and “put my soul” into a letter to Cope, applying to be his fossil scout and requesting a $300 grubstake.

“I like the style of your letter,” Cope wrote back, enclosing a check for $300. It was the start of a beautiful partnership.

The Life of a Fossil Hunter offers a lively portrait of the impulsive and driven Cope. That summer, he and Sternberg and their crew set out for Montana a few weeks after Custer’s debacle on the Little Big Horn. Naturally, Cope was urged to give the Sioux a wide berth, but on the theory that white Americans’ outrage over the Last Stand had left the Sioux in disarray, he insisted on pushing ahead. He called it right; his party was not interfered with.

They found plenty of fossils, but what stands out most from that season in the field is Cope’s stubbornness. One night in October, trying to reach the last scheduled steamboat of the year, Cope and company drew up above a gorge that yawned between them and the Missouri River. Cope decreed that they must reach the rendezvous point, on an island below, that same night.

“I knew the uselessness of trying to combat his iron will,” Sternberg wrote, “but I pleaded with him against the folly of trying to thread in the darkness those black and treacherous defiles, where a single misstep meant certain death.”

The implacable Cope dismounted and led the way. “He had to cut a stick to shove in front of him, as his eyes could not penetrate the darkness a single inch ahead. I cut another [stick] to punch along his horse, which did not want to follow him. Sometimes when we had climbed down several hundred feet, the end of the Professor’s stick would encounter only air, and a handful of stones thrown ahead would be heard to strike the earth far below. Then we had to turn and climb back through the deep dust to the top, and circling a canyon, plunge down the other side.”

They got down safely, but you can almost hear Sternberg gulp as he wraps up his anecdote: “I have never known another man who would have attempted this journey. It was both foolhardy and useless, but we could say that we accomplished what no one else ever had in reaching Cow Island through the Bad Lands after dark.”

Cope’s willfulness had combined with overwork, bad food, and alkaline water to plague him with nightmares that summer. “Every animal of which we had found traces during the day played with him at night,” Sternberg recalled, “tossing him into the air, kicking him, trampling upon him. When I waked him, he would thank me cordially and lie down to another attack. Sometimes he would lose half the night in this exhausting slumber. But the next morning he would lead the party, and be the last to give up at night. I have never known a more wonderful example of the will’s power over the body.”

For all his frenzies, Cope evidently knew how to relax. Sternberg spent the winter of 1876-77 with the Copes, first in Haddonfield, then in Philadelphia, where they moved into a pair of adjoining houses at 21st and Pine streets. “I shall never forget those Sunday dinners,” Sternberg wrote. “The food was plain, but daintily cooked, and the Professor’s conversation was a feast in itself. He had a wonderful power of putting professional matters from his mind when he left his study, and coming out ready to enter into any kind of merrymaking. He used to sit with sparkling eyes, telling story after story, while we laughed at his sallies until we could laugh no more.”

Sternberg went on to collect fossils for many other scientists, Marsh included, and sold his finds to museums in New York, London, and Berlin. But he singled out his work for Cope as his “most valuable service to science.”

The Bone War escalated. To Cope, Marsh was an imperious plodder; to Marsh, Cope was a grabby prestige-hound. Marsh accused Cope of backdating his work so as to be recognized as the discoverer of species; Cope hotly denied this. Since being first to describe a species entitled one to name it, some creatures went by two names—one given by Cope and one by Marsh—until neutral third parties sorted things out.

As Cope and Marsh leveled charges and counter-charges in learned journals, their rhetoric turned acidic, as the following examples attest.

Marsh: “[Cope’s errors] are without parallel in the annals of science.”

Cope: “It is plain that most of Prof. Marsh’s criticisms are misrepresentations, his systematic innovations are untenable, and his statements as to the dates of my paper are either criminally ambiguous or untrue.”

The editors of one journal had enough. They announced that further rounds of the bout would be consigned to appendices which the two boxers themselves would have to fund. Cope and Marsh paid up and went on slugging.

Things were no better out in the field. In the late 1870s you could have found Cope and company at work surrounded by Marsh’s men in the Como Bluff region of Wyoming. That was one of the sites where spying allegedly took place (based on his description, one snoop might have been Sternberg, although he says nothing about spying in his book). Both principals were now cranking out articles based on scanty information and battling over such niceties as whether a detailed telegram qualified as a scientific publication. The result, according to 20th-century paleontologists David Berman and John McIntosh, was “confusion and misconception about the animals [Cope and Marsh] described that lasted long after their deaths.”

Unseemly as the brawling was, it had been mostly confined to the small world of natural scientists. But in 1890 Cope went public, feeding his grievances to a freelance journalist named William Hosea Ballou, who sold a story on the subject to the scandal-mongering New York Herald. “SCIENTISTS WAGE BITTER WARFARE,” the piece was headlined.

The furious Marsh gave Ballou his side of the controversy, and Ballou happily wrote more articles. By then Cope was teaching at Penn—first geology, later comparative anatomy—and Marsh demanded that the University’s provost, William Pepper C1862 M1864, fire Cope for spreading libels. It was rumored that Marsh had something scandalous on Pepper, which Marsh threatened to expose if he didn’t get his way. Cope was worried enough to ask his protégé Henry Fairfield Osborn to intercede.

How Osborn became Cope’s friend, and not Marsh’s, tells us something about the two older men. While Osborn was a senior at Princeton, he and a classmate had approached Marsh for advice in planning their own dinosaur-hunting expedition in the summer of 1877. Marsh brushed them off, so they turned to Cope—who assumed they were in cahoots with Marsh and gave them the same treatment. When Cope discovered his error, however, he made an about-face, giving Osborn access to his collections and even traveling to Princeton to help the young men sort through the fossils they’d brought back.

Thirteen years later, Osborn was a rising star (he eventually became president of the American Natural History Museum in New York). So when he came to Philadelphia to plead Cope’s case, Pepper listened—and resisted Marsh’s blackmail attempt, if indeed it was made. Cope kept his job. Following its public airing, the Bone War cooled down, but Cope and Marsh never reconciled.

Cope needed his Penn job. He’d spent much of his inheritance on acquiring fossils and squandered the rest on bad mining investments. He’d also overtaxed his wife’s patience; they lived apart during the last years of his life.

When he died in 1897, at age 56, of a gastrointestinal illness, Cope had more than 1,400 scientific publications to his credit, five times as many as Marsh. Although Cope named “only” 56 dinosaurs compared to Marsh’s 86, most of their peers considered Cope the more brilliant thinker of the two. Besides his finds, he is remembered for Cope’s Rule, which hypothesizes that as species evolve they tend to grow in size. (For more on Cope and evolution, see “Darwinism Comes to Penn,” Nov|Dec 2009.)

Cope could probably have gotten away with coasting through his years as a Penn professor. But that was not the Cope way. “His memory was rich and accurate,” Osborn recalled, “and in addition to his regular class work he fashioned his varied experiences into instructive and entertaining lectures … When Cope began his courses … he soon discovered that his theories and materials were far in advance of any text-book … he set about writing his own.”

Dennis Drabelle G’66 L’69 is the author, most recently, of The Great American Railroad War.