A Filipino filmmaker casts a wry eye on the gulf between East and West.

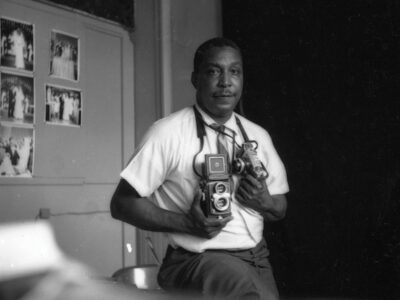

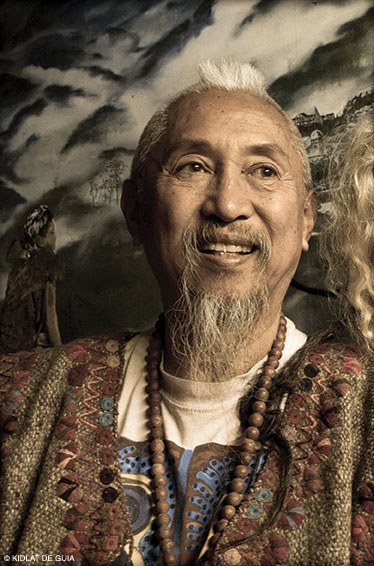

By Karen Fang | The Wharton School has its full share of alumni who have left their mark on the world. Kidlat Tahimik WG’67 (above) may be the only one to have done so while wielding a bamboo camera, dressed in a loincloth. An internationally acclaimed filmmaker who has been called the “Father of Philippine Independent Cinema,” the 73-year-old Tahimik has been making deeply personal, idiosyncratic films for almost four decades now, drawing on his Filipino heritage to critique Western power.

Tahimik, whose name means “silent lightning” in Tagalog, was still known as Eric de Guia during his Penn days. Although his style is often described as naïf or primitive due to his lack of formal film training and the innocent, childlike persona he depicts in his films, his work encodes a subtle but ardent critique of capitalism and American influence. His latest film, Balikbayan #1, weaves together historical materials and speculative dramatization to imagine the experiences of Enrique de Malacca, a Southeast Asian slave acquired by the 15th-century Spanish explorer Ferdinand Magellan. Balikbayan translates as “repatriate” or “returning to one’s homeland,” and while the title refers to the protagonist whom Tahimik portrays, it also describes Tahimik himself, who is finally completing the story that he began so many years ago. His 1977 debut film, Perfumed Nightmare, which centers on the hopes of an idealistic Filipino villager enthralled with the American space program,was hailed as “one of the most original and poetic works of cinema made anywhere in the Seventies” by director Werner Herzog. Six years after its completion, it won the International Film Critics Award at the Berlin International Film Festival. Last year Balikbayan #1 won the Caligari Prize at the same festival.

Scenes from Balikbayan #1 (above) and Perfumed Nightmare (below).

The subtitle of Balikbayan #1 is Memories of Overdevelopment Redux, playing off the economic concept of “underdevelopment” used to describe inequality between rich and poor nations—a subject that Tahimik studied while earning his Wharton MBA and during his brief stint as a research consultant for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (He has been known to say that he “studied LSD” at Penn—adding, after a long pause: “You know, the law of supply and demand.”) Balikbayan #1 shares with all of his previous works a minority perspective that rejects conventional assumptions of Western superiority.

Of course, as a Philippines citizen and particularly as a child growing up in Baguio City, an area long marked by American military influence, Tahimik has long had a complicated relationship to the Western cultures surrounding him.

“Like everyone from the Third World,” he says, “I had always wanted to go to America.” His childhood fascination with American achievement is wonderfully conveyed in Perfumed Nightmare. So is his later disillusionment. When Tahimik/de Guia arrived at Penn in the fall of 1965,he had some culture shock to deal with.

Philadelphia “was the first place where I saw a white person working as a housekeeper,” he says. That breakdown in his romanticized notions of American privilege and his growing disenchantment with America’s global influence has been a recurring subject of his films. In Why Is Yellow the Middle of the Rainbow? (1994), Tahimik wove together news footage of Philippine elections and other key moments in national history with home movies shot over a 15-year-period. The latter included deeply personal memories of a road trip he and his son took in the US—from hitching a ride with Dennis Hopper in the actor’s Cadillac, to a car-proud housewife who mystified the pair with her endless trips to the car wash, to some iconoclastic but loving images from Monument Valley, where the patriarch of a local family they befriended posed for tourist photos in the style of Hollywood Westerns.

Tahimik himself often plays with costume and “native dress” as part of his film persona. Since the 1980s, he has been adding performances to many of his screenings, dressed in the elaborately embellished loincloth and vests of the Ifugao tribe near his father’s home village of Balian and carrying a wicker “camera” improvised from a traditional fish trap—to which two reel-like shapes have been added. Although the bamboo camera is not functional, Tahimik often gives copies to aspiring young filmmakers in the Philippines as a reminder to encourage them to buck Hollywood formulas and seek the stories within themselves. His term for this is duende, a Spanish term first developed by Federico García Lorca and now commonly used by Filipinos to describe a mystical, natural spirit—a response of the soul, if you will. It’s a concept that—in typical Tahimik fashion—often surfaces in his conversation alongside allusions to economic theory and global geopolitics. Confessing that he once was a “normal Filippino kid, overdosed on Hollywood films,” Tahimik believes that trusting duende instead of formal training enabled him to find the “many beautiful stories that are being bypassed because of box office.”

Tahimik’s ties to Philadelphia and Penn are still alive after all these years, and he remains in touch with a member of the host family that was his first local contact in the city. Even Benjamin Franklin serves as a touchstone for his own idiosyncratic filmmaking style, and as he discusses Balikbayan #1,Tahimik peppers his conversation with aphorisms from Penn’s founder. Though Franklin’s famous phrase “time is money” takes on an ironic, even subversive note when positioned against Tahimik’s extremely slow-paced, open-ended filmmaking, the references show the extent to which Philadelphia and the University continue to leave their imprint on the vision of one of world cinema’s most original independent filmmakers.

Karen Fang C’94 is an associate professor of English and film studies at the University of Houston.