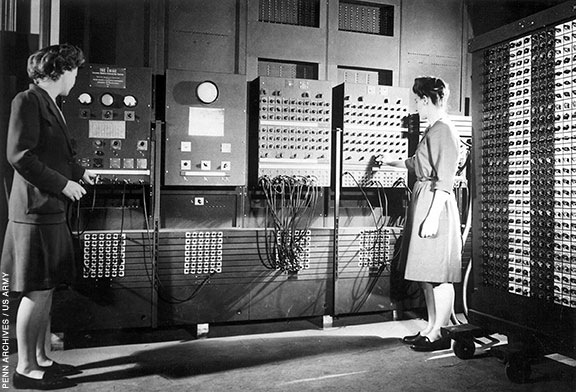

Betty Jean Jennings (left) and Fran Bilas (right) operate ENIAC’s main control panel at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering.

If you’re a fan of The Imitation Game and Walter Isaacson’s 2014 bestseller The Innovators, be glad you weren’t on campus to hear Thomas Haigh G’97 Gr’03 speak at ENIAC’s 70th anniversary in February. He described the former as a “terrible, terrible film,” while the latter, he warned (truthfully), would “be a bit of a punching bag for me today.” His objections had less to do with aesthetics than the way both works—along with most accounts of computer history, whether billed as fiction or fact—misrepresent how technological progress occurs and leave out lots of the people who make it happen.

Haigh earned his doctorate in the history and sociology of science at Penn, and is currently an historian of technology and labor and the history of computing at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. He’s a coauthor, with Mark Priestley and Crispin Rope, of the new book ENIAC in Action: Making and Remaking the Modern Computer (MIT Press).

The “Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer” developed at Penn hasn’t lacked for attention since its 1946 debut, but ENIAC in Action claims in its introduction to be the “first comprehensive examination of its use as a scientific instrument.” In his talk, “Working on ENIAC: Rethinking the Myths of Innovation,” Haigh also proposed a much more inclusive approach to defining who deserves credit for its success.

“The conventional history of computing was very much a battle for firsts,” Haigh said. “It’s like rival teams who would be cheering for their own firsts. And that basically meant pitching rival geniuses.”

He cited The Imitation Game as a near-perfect example of this template. In the film, Benedict Cumberbatch—famed, among other roles, as TV’s Sherlock Holmes—portrays one such rival, Britain’s Alan Turing, as “another borderline-autistic solitary genius who designed and built a computer all by himself.”

This despite the fact that the device in question, designed to crack Nazi codes during World War II, was not “really a computer, and they built hundreds of them on an industrial scale,” Haigh added. “It was a major, major project with industrial subcontractors and literally thousands of people involved. But the story that we like to tell about that is the lone genius who builds the thing with his bare hands.”

As for The Innovators (which Isaacson visited campus to discuss at the 2014 Silfen Forum [“Gazetteer,” Jan|Feb 2015]), Haigh acknowledged that it offered a lively narrative and made skillful use of scholarly and other sources, but charged it with falling into the same trap, only with a larger cast of characters. The book does stress teamwork and collaboration, but the subtitle—How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution—gives the game away. Haigh likened it to Marvel Studios’ blockbuster The Avengers, in which Iron Man, Thor, Captain America, et al. partner up to thwart an alien invasion: “They’re still superheroes, but they have to work together to save the world.”

As for whether ENIAC—or any other claimant—was the first computer, “you’ll never get a good historian to give you a straight answer,” Haigh said. “We kind of agree to split the trophy, and everyone gets the first with a whole bunch of adjectives. So ENIAC is the first electronic digital general-purpose computer. And that’s generally seen as a step, an important step, on the pathway [to] the present-day computer.”

The focus on firsts also “tends to boil each computer down to a single date. That’s not the path we’re taking,” Haigh said. Such a view is difficult to get away from—he was on campus to mark ENIAC’s “anniversary,” after all—but it misses a lot.

“It doesn’t care at all about what computers were used for or how they were used,” he said. “And that’s basically why we thought we needed to put ENIAC in action, and the action is stressing that it’s not just a thing and a first, it’s a machine that actually existed, had a materiality, had users. It did stuff.”

Haigh offered a quick sketch of ENIAC’s history: the project was approved in 1943; planning and prototyping took place in 1944, with full-scale production under way in the latter half of the year; construction continued in 1945, “and by autumn they’re into debugging.” After the fanfare surrounding the public unveiling—don’t get him started on how that’s been mythologized—the machine was used throughout 1946 at the Moore School. Then, “in 1947 they knock a hole in the side of the wall, drag the machine out, ship it down to Aberdeen Proving Ground” in Maryland, where it remained in operation until 1955, when it was decommissioned.

One detail that vividly brought the material aspect of ENIAC home was an anecdote Haigh related about acquiring a supply of a particular type of wire that was needed for the machine; only no one could remember what it was. They cut up the wire and sent out cards with samples to different suppliers, asking if it was their product.

During construction, they also had to deal with two floods and a fire at the Moore School in the fall of 1945. Haigh emphasized the sheer number of people involved in developing and building ENIAC, from the famed duo of John Mauchly Hon’60 and J. Presper Eckert EE’41 GEE’43 Hon’64 to Isabelle Jay, who “was the project secretary, working I think full-time throughout the duration.”

The role of physical construction has been “completely underappreciated,” Haigh said. “Early in the project you’ve got the design engineers and a few people helping to make prototypes. But when they start shifting to actually building ENIAC, they need way more people.” By the end of 1944 there were seven design engineers, three people doing mechanical design and drafting, and another three model makers.

But there were many more doing the production and building the machine, he said. By studying accounting records, Haigh was able to find the names of 50 women working on the project during 1944 alone. “And there’s not much we can do for them at this point,” he added. “I’m afraid all we could literally do was make them a footnote to history—because these names appear in a footnote.”

Once the machine was up and running, there was the business of operating it, which involved “a kind of physicality [that] tends to be forgotten,” Haigh added. “To get the data ready and to process the input and output, even for the simplest job, [ENIAC] had to be used in cooperation with other kinds of punch-card machines.” This work “required an enormous amount of skill on the part of the operators. And they were doing some of the work that we now think of as being part of the program of carrying out those other steps beyond what the computer itself could automate.”

Haigh contrasted this truly obscure group with the six women programmers celebrated in The Innovators, who joined the project in 1945 after working at the Moore School doing similar calculations to those ENIAC was designed to perform, only by hand or with other technologies. Given the “enormous problem” that the IT industry has with underrepresentation of women, Haigh said, it’s not surprising that Isaacson and others would turn to history in search of “role models to say, ‘Look, in history, women did great things. You should come into this field, too.’”

Not surprising, just less than the whole story.

With regard to The Innovators specifically, Haigh quarreled with Isaacson’s assertion that all the engineers who built ENIAC’s hardware were men. “If he knew anything about what engineers did, and the difference between designing something and building something, he wouldn’t say that,” Haigh said. “But if he looked a little bit, he’d know that the people who built ENIAC’s hardware predominantly actually were women.”

As for the complementary claim that all the programmers “who created the first general-purpose computer were women,” aside from the fact that programmers don’t actually create computers, “there’s the bigger question: when so much of their work was hands-on operations work, why do we remember them only as programmers?” he asked. “It’s great to celebrate girls who code, and role models are great. But shouldn’t we maybe also remember women who operate?”

More fundamentally, the problems with the “great man theory of history” go deeper than can be solved “by just adding a few great women,” he added. “Because the kind of work that history has allowed women to do has been more in the background or in lower status roles.

“And [instead of] just saying, ‘Oh, it turns out there are these women geniuses you never heard about to go with the men geniuses,’ maybe we should rethink more broadly what is the kind of work that deserves to be remembered in innovation.”

By the 1950s, computer operations and keypunch work had lower status than programming. It’s no coincidence that those tasks also constituted the computer work most likely to be done by women, Haigh said. “So saying that operations work is not worth remembering, but programming work is, is not some kind of great feminist statement.”

The current emphasis on cloud computing is the IT industry’s way of “trying to forget that data has any kind of materiality, that there’s really any underlying infrastructure,” Haigh said. “In a similar way this focus on geniuses, conceptual breakthroughs, and programming has hidden the historical reality of the materiality and the kinds of labor involved in early computing from view.”

Rather than a tale of “hackers, geniuses, and geeks,” Haigh said, the true history of the digital revolution is closer to the “ironic proposal” he credited to a friend: The Maintainers: How a Group of Bureaucrats, Standards Engineers, and Introverts Made Digital Instruments That Kind of Worked Most of the Time. “Successful IT innovations always depended on the things that we don’t think of in that kind of ‘geniuses and geeks’ way—execution, operations, logistics, doing the little things well.”

That was the case with ENIAC, too. The machine’s development “was a remarkable collaborative effort,” Haigh said, from the support in funding, materials, and expertise provided by Penn and military authorities to all the workers directly involved in the project. “They did their job well enough in challenging times. And even without superpowers, they changed the world. All of them. Even the secretary and the draftswomen and those women whose names we have forgotten.” —J.P.