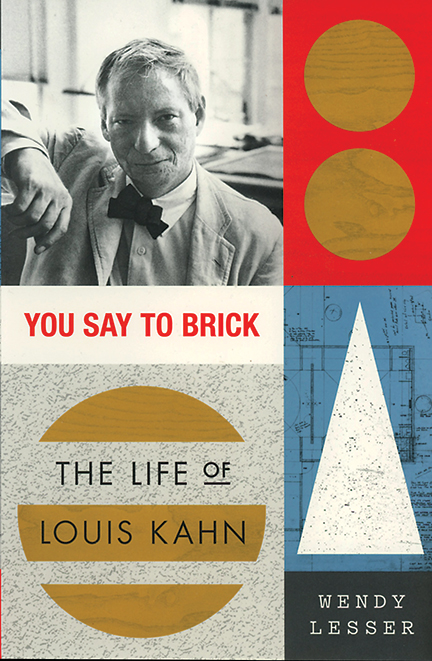

YOU SAY TO BRICK: The Life of Louis Kahn

Wendy Lesser

Farrar, Straus Giroux, 2017, $30.

By George H. Marcus | With the nose of a bloodhound, Wendy Lesser has sniffed out every last detail of the life and death of Penn’s revered professor of architecture, Louis Kahn Ar’24 Hon’71. Ever since his ignominious death in the men’s room of New York’s Pennsylvania Station in 1974 (in truth, even before), architectural historians have been endlessly dissecting his work and his words, but not until now do we have a full-scale biography of this conflicted genius. It has taken Lesser, a critic of culture, not architecture, to complete this task, and she does a compelling job of it.

The lame and perplexing title, You Say to Brick, should be ignored, however, until one comes across it in the book, where it appears in one of Kahn’s legendary remarks: “You say to brick, ‘What do you want, brick?’ Brick says to you, ‘I like an arch.’ If you say to brick, ‘Arches are expensive, and I can use a concrete lintel over an opening. What do you think of that, brick?’ Brick says, ‘I like an arch.’” This quirky dialectic was at the heart of Kahn’s philosophy; he believed that every material has its own nature and that it is up to the architect to honor that nature in determining how to construct a building.

While the basics of Kahn’s life could be found in Carter Wiseman’s hybrid study, Louis I. Kahn: Beyond Time and Style, A Life in Architecture (2007), Lesser has added enormously to his story by tracking down and interviewing scores of friends, family, associates, and staff. (Because he hired young graduates, many of them are still around to provide insights into the workings of his office.) Her leitmotif is a staccato of voices offering contradictory perspectives on the man they admired.

But the story of his death comes first. Ever since word got out about its baffling circumstances, the account of his last hours and the frenzy that followed for those trying to locate him has been plagued with rumor, hearsay, and misunderstanding. In the first 30 gripping pages, Lesser revisits every stage of mistake and mishap, and with forensic evidence in hand, finally closes the book on these confusions.

Equally gripping is the story of his funeral, where the amorous entanglements of his life are laid bare—his wife, Esther Kahn Ed’27 G’33, trying to will away the sight (and knowledge) of his two mistresses: Anne Tyng Gr’75 (who brought his daughter Alex Tyng GEd’77) and Harriet Pattison GLA’75 (who came with his son, Nathaniel).

For those who collect infidelities, this book provides additional riches. The first shocker is that Kahn had another entanglement, with Marie Kuo, a Penn architectural graduate from an aristocratic Chinese family that had fallen on hard times after immigrating to the United States. She began to work in Kahn’s office soon after Anne Tyng left for Europe to give birth to their child out of sight in Rome. This new affair was shorter and less intense than the others, but it was still going on when Tyng returned. Apparently, Kuo visited Tyng to ask her to give up her relationship with Kahn on the grounds that Tyng already had his child. Tyng was able to keep track of the liaison by listening to Marie’s telephone conversations with her mother, one of which concerned contraception. Marie did not realize that Anne, a missionary’s daughter who had grown up in China, was fluent in Mandarin.

A second revelation is that Esther, the “aggrieved” spouse, also had been having an affair with a research scientist from Penn (whose name, curiously, is never revealed). Kahn appears to have been too absorbed in his work to recognize any signs of Esther looking elsewhere for affection.

Between chapters, as if to relieve the mundane with the majestic, Lesser interposes short architectural essays in which she relates her own visceral responses to five of his masterworks—the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, the Phillips Exeter Library in New Hampshire, the National Assembly Building of Bangladesh in Dhaka, and the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad. Her gift for descriptive detail and her analyses of architectural intricacies help lead readers deeper into Kahn’s work, though the accompanying black-and-white photographs are lackluster.

Although she writes forcefully about these great structures, this book is not about architecture but about the man whose genius made them happen. His genius was not his alone, however; he was supported by a devoted staff, and the way Lesser describes the office and the drafting room makes you wonder how it could have happened at all. His architects would work long hours under great pressure, putting in 60 or 70 a week when a project was in full swing, and Kahn often worked along with them. But he was mercurial, alternately praising and deprecating their work, and tensions could run high, especially because the office was frequently behind with their pay. Perhaps the best assessment of Kahn’s behavior was that of Steven Korman, for whom Kahn had built a palatial country house in the Philadelphia suburbs: “He didn’t want to hurt people. He did, but he didn’t want to.”

George H. Marcus, adjunct assistant professor of the history of art at Penn, is the author of several books on design and the co-author (with William Whitaker GAr’96 CGS’99, curator of Penn’s Architectural Archives) of The Houses of Louis Kahn.