Charles Krause spent most of his career digging for stories. Now he’s finding—and exhibiting—artists whose work impacts the world.

BY SAMUEL HUGHES | Photography by Candace diCarlo

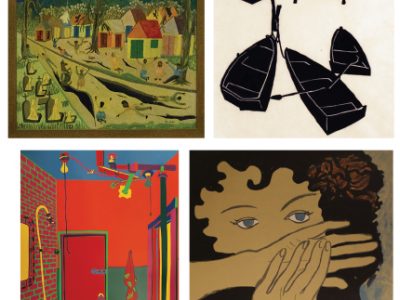

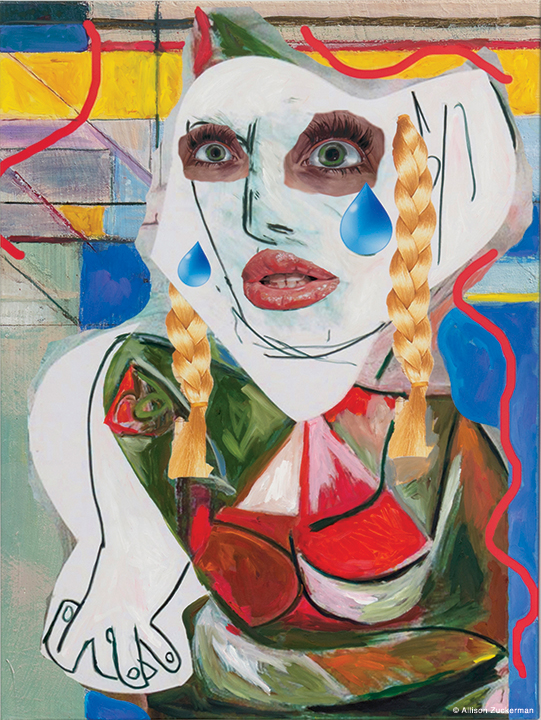

Sidebar| Exhibitions from a Man on a Mission

Charles Krause C’69 is sitting in the cool, curving, contemporary condo that functions as his home and his fine-art gallery. His expression is somewhere between serious and worried, though truth be told, his wooly-bear eyebrows make him look kind of anxious when he’s just making a pot of coffee. But Krause has had his full share of real things to worry about over the years, and he does now, too.

True, he’s no longer getting shot in places like Jonestown, as he did when he was the South American bureau chief for The Washington Post,or covering the breakup of the Soviet Union for PBS’s NewsHour, or crossing the Kuwaiti border in a tank with the Desert Storm troops during the first Gulf War. These days his concerns revolve around his Washington gallery, Charles Krause/ Reporting Fine Art—things like how to cover the costs of transporting art from Estonia (he can’t go to Russia because the Putin regime took away his visa), planning the minutiae of receptions and openings, and figuring out which art magazines give the biggest advertising bang for his buck (none, so far). Underlying it all is the larger question of whether he can make any money at this new and risky endeavor, which he has undertaken at an age when most of his peers are either retiring or trying to beef up their 401(k)s in the safest manner possible.

Which is not to say that he’s turned his back on world events. Part of Krause’s self-appointed mission is to showcase artists “whose work has influenced, or has been significantly influenced by, the great social and political upheavals of the 20th and 21st centuries.” The other part is to “change the way their work is seen, understood, and valued by museum curators, art collectors, policymakers,” and policy-conscious citizens.

“I’m trying to introduce art that hasn’t been seen in this country before, by artists whose work I think merits international recognition,” he says. “I’m also trying to redefine the values that go into aesthetics.”

Those are ambitious goals. They have also been roiling inside him for years. If journalism was his career—one that brought him his share of awards and plaudits—art has been his passion. Ever since he was a teenager from an art-loving family in Detroit, he saw himself opening his own gallery one day. (His high-school graduation present was any work he wanted from a local gallery; he chose a Calder lithograph.) That the gallery would open in his Logan Circle condo may not have been part of the original vision, though it does offer certain advantages of economy and convenience.

“What I’m doing now is an extension of the one career and an extension of something else that I have always also been interested in,” he says.

After his journalism career wound down, he took a hard look at the work he had gathered during his travels. By the standards of Serious Collectors, he concluded, his collection might be deemed scattered and unfocused—everything from an 18th-century oil portrait of the last Inca by an anonymous Peruvian artist, to the works of Soviet Nonconformist artists, to a Chilean abstract expressionist named Joan Belmar. But then he looked at it again, from another vantage point.

“And I thought, ‘The art of social and political change—that’s valid. And it has an impact that hasn’t been recognized,’” Krause says. That idea was worth exploring, he decided, though he had to be careful that it didn’t detract from the overall quality of the work being shown. “It still has to be great art,” he emphasizes. “Just because an image has an impact doesn’t mean it’s great art.”

He thinks about that a little more, then says:

“I guess what I’m saying is, ‘Here we are in the 21st century. We’ve been through abstract expressionism. We’ve been through postmodernism. We’ve been through all this stuff. How about art that actually impacts what happens in the world?’”

It’s late on a sweltering mid-summer afternoon in the nation’s capital, and inside his air-conditioned condo/gallery, Krause is speaking to a dozen or so Penn students who are getting a private tour as part of the Penn in Washington internship program. He’s been pretty involved with the University over the years, having served for three years as a young alumni trustee back in the early 1970s and participated in the occasional alumni event for The Daily Pennsylvanian, where, as a student (then known as Chuck) majoring in political science, he had risen through the ranks to become editor-in-chief. Now he’s telling them a little about his journalism career, beginning with his stint with The Washington Post.

“I guess the first big, big story that I was involved with that you would know of is ‘Don’t Drink the Kool-Aid,’” he says. “Does anyone know where that comes from?”

Only one student offers an answer, and while she gets the gist of it right, she’s a little fuzzy on the details. Which is hardly surprising; the murders and mass suicide at Jonestown took place more than a decade before these kids were born. So Krause fills in some of the details, though he is so reluctant to dramatize his own story in conversation that it doesn’t really pack the punch that it could.

Consider, for example, this snippet from Guyana Massacre: The Eyewitness Account, which Krause, aided by a team of Post writers, knocked out in six days, and which sold upwards of 250,000 copies in half a dozen languages (it was later made into a riveting TV movie):

The shots were louder and closer now. Someone landed on top of me and rolled off. I could feel dirt spraying over me, but there were no screams or moans. Just the pop-pop-pop of the bullets. The shots were coming from one side of me and from the rear, and I knew I was on the wrong side of the plane. Suddenly, my left hip burned and I felt a tooth chip. I knew I had been hit.

I was thinking, this is crazy. It couldn’t be. I was going to die in the middle of the jungle, in Guyana, so far away from my family and friends. I thought about the coming Thanksgiving.

I wasn’t going to be there. I was going to be dead. It was all so unfair, so unjust, so ironic. I was here working. I had nothing to do with the People’s Temple. I did not want to destroy it.

I hadn’t believed it was what its detractors said it was. How stupid, I was thinking. How Goddamn stupid I’d been.

It’s an extraordinary story, though as Krause makes clear, he was only a lucky survivor, not a hero. He had known virtually nothing about the People’s Temple when he reported to Guyana, and during his brief tour of the compound with Congressman Leo Ryan and some other journalists he had not grasped the truly evil mindset of Jim Jones that led to 900 men, women, and children committing mass suicide or being murdered. But he survived the terrifying ordeal, and made up for what he had missed with coverage that won the Overseas Press Club’s Hal Boyle Award.

Two years later, Krause switched over to the broadcast side of journalism as a correspondent for CBS News, where he reported on, among other things, a Cuban artist named Roberto Fabelo. In 1983 he moved to PBS and its NewsHour, spending 16 years as the program’s senior foreign-affairs correspondent. He covered everything from the Middle East—his reports of the 1996 Israeli elections won an Emmy—to Operation Desert Storm and the breakup of the Soviet Union. Wherever he went he followed his nose for art, tracking down artists the same way he tracked down stories of political dissent.

His first Russian love was Soviet propaganda art, but he soon discovered that there were other artists in the Soviet Union who had refused to paint in the official socialist-realism style. It wasn’t until more than a decade later that he first saw some of the Nonconfirmists’ work at the state Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

“I was stunned, amazed, simply blown away by what I saw and vowed to myself that I would learn as much as I could about them and build a collection of their art,” he told Russia Behind the Headlines’ Nora FitzGerald, “both because many of them were extraordinarily inventive and original and because of the example they set and the risks they took to create art that, in and of itself, made a political statement even if there was nothing else political about it.”

By then, ironically, Krause had left journalism. It can’t have been an easy decision, even though, for all his skills as a reporter, broadcast journalism had been a difficult medium for him. As a speaker—at least as an interview subject—he’s more of a writer, one who constantly edits himself as he goes along.

“I wasn’t a natural-born actor or presenter,” he acknowledges. “I never, ever developed a natural delivery, which you really must have. I was a good reporter, and that got me to a certain point. But unless you can deliver it with a kind of style, you’re only going to go so far.”

As a result, he more or less hit a wall at the NewsHour.

“I wanted to be an anchor at PBS,” he says. “I wouldn’t deny that for a minute. And it just didn’t seem like it was going to happen. At a certain point, you start to think, ‘If this isn’t going where I want it to go, and I’m just increasingly frustrated by this whole thing, how do I get out of it?’”

A somewhat circuitous path led him to APCO Worldwide, an international public-relations and communications firm, where he became a senior vice president. On the surface, it was a surprising career move, though it led him to some important connections.

Robert Amsterdam, an activist lawyer and founding partner of the Toronto law firm Amsterdam & Peroff, first met Krause when they were both working on the case of Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the billionaire Russian petroleum executive who was imprisoned by the Putin regime on tax evasion and other charges; the case was widely considered to be politically motivated. Amsterdam represented Khodorkovsky in court, and was expelled from Russia for his efforts. Krause was representing Khodorkovsky in the court of public opinion on behalf of APCO. The Putin administration took away his visa.

Amsterdam, who grew up watching Krause on CBS and the NewsHour, describes him as “an incredibly heroic, courageous, principled individual,” and says that he invariably “put himself in the middle of the action, whether it was in Latin America or Russia.”

“Charles is a political actor,” Amsterdam adds. “That’s what I find so interesting about him. He’s not a sideline communicator. He is somebody who transmits the truth of a political conflict in a way that is incredibly unvarnished, unbiased, and real.”

For Krause, having his visa revoked was both a blow to his collecting and a grim reminder of the rough capriciousness of power.

“The whole Khodorkovsky affair affected my view of Putin,” and not just because of the visa, he says. “But the point is that it isn’t one individual, really. It’s the system. The KGB or the FSB is certainly a part of it, and they’re the ones who decide if they’re going to take your visa away. They did it totally arbitrarily.

“It makes me sad, because I like Moscow,” he adds. “I like Russian art. It’s meant that I’ve had to buy the art at auctions or in other places—not in Russia.”

Amsterdam recalls traveling with Krause in Russia: “He would be talking to people in the art community and out looking for that kind of work, and frankly, he left me in the dust. He knew everybody in the arts community in Russia. He would be going to their very remote shows, and strange apartments in God-knows-where. I wasn’t part of that milieu.

“He brings a whole different sensibility to the kind of political art that we’re dealing with,” Amsterdam adds. “There aren’t many [collectors] who’ve been in the field, who’ve experienced repression, who’ve experienced a fear of torture—I mean, he’s seen and done it all, and at the same time now he gets to sort of curate it and collect it. It’s a very exciting combination.”

Amsterdam is underwriting Krause’s upcoming exhibition: Defining the Art of Social and Political Change (see page 54), which will open sometime in February.

“I’ve never sponsored anything like this before in my life,” says Amsterdam. “The only reason I’m doing it is because I think it’s so important. We’re living in an incredibly complex world, where Americans in particular need to understand the different shades of gray that are involved. And I think what Charles is trying to do is provide a platform in elevating the public discussion. If you find something which speaks to you, is real, and which elevates the discussion about important political themes, then from my standpoint, you need to reach out to support it.”

Mark Jenkins, who writes the “Galleries” column for The Washington Post, was intrigued when he learned that Krause was opening his gallery in late 2011.

“At first I wasn’t sure what sort of work he was going to exhibit,” Jenkins says, but “after seeing several shows, it’s clear that he has a wide definition of what constitutes political art. I think that bodes well for the gallery, although it also makes it harder to explain the concept quickly to people who might be interested.

“It’s novel for a gallery to have such a thematic focus, unless it’s connected to some larger institution with an agenda,” he adds. “There are galleries and arts spaces that do only one medium—photography, say, or sculpture—but it’s rare for one to define itself this way.”

The exhibitions have been “strong and diverse,” in Jenkins’ view. “He’s not just showing agit-prop posters—although I wouldn’t mind that. The work has been well crafted, and the political aspects of it [are] often subtle.”

Despite its political content, the work Krause has exhibited has not exactly been polarizing or controversial. It’s hard to imagine any visitors being offended by Solidarity posters or works by Soviet Dissident artists, and even the recent show by Chilean immigrant Joan Belmar—despite the underlying suggestion that it’s a good idea to support immigrants, not deport them arbitrarily—is too abstract to raise political hackles.

I recently asked Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, associate professor of American art at Penn whose interests include political art, to take a look at Krause’s website. In a sense, she says, it’s less provocative than political galleries like the Galería de la Raza in San Francisco or the Kenkeleba Gallery in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, which “tend to be on the fringes of the mainstream, in part because they emphasize work by artists of color, but also because that work can be both galvanizing and polarizing.

“But it’s nice stuff,” she adds. “He has the real eye for high technical ability and strong compositional strategies. And it’s so diverse—it’s really stuff from all over the world, isn’t it? I think in some ways it reads as postcards from his travels.”

The question of why contemporary-art museums (and, by extension, galleries) “tiptoe around” political work of all stripes is a complicated one, noted Randy Kennedy in a recent New York Times essay. “Partly it is a legacy of the ’80s and ’90s culture wars that threatened public funds for the visual arts and that continue to make many institutions wary of offending any constituencies,” he wrote. Another practical concern is that political art is often rejected by the public “as one-dimensional, as visually dull, as too divisive or as all of the above.” Which leads back to Krause’s early point—that his top priority is to show great art, not just art that makes an impact. (Krause also suggests that the fear of showing political art may be a legacy of the Cold War, when the American art scene was “traumatized and depoliticized as a result of the McCarthy era.”)

“What is it we value in contemporary art?” Krause asks. “What makes this artist’s work important and this artist’s work not? With the criteria we use, it would be just as valid to say that this piece demonstrates political courage, and that’s a trait that we want to encourage and is important, and therefore there ought to be a premium paid for art that accomplishes something. But that isn’t, right now, the way it is.”

Krause doesn’t try to hide the fact that if, by some miracle, he can push the American art needle a little more in the direction of dissent, his own collection stands to benefit from the bump. So far, for a very small gallery in a not-very-commercial section of town, one that often requires visitors to make appointments, Charles Krause/Reporting Fine Art has received a pretty impressive amount of press coverage, from The Washington Times to Artforum, Business Week to Eyemazing. Krause has also sold about two dozen pieces, though it’s fair to say that he has a ways to go before he’s in the black. “Everyone who comes seems to find all this very interesting,” he says drily. “They just don’t buy.” (As of late November, he was hopeful that the Hidden Treasure exhibition of works by Joan Belmar would break even, which would represent “a giant step in the right direction.”)

“I can’t forecast the commercial prospects,” says the Post’sJenkins. “Art is too quirky a business. I think this sort of gallery could do well in Washington, but attracting attention is difficult. There are a lot of distractions out there, and just keeping up with the museums in DC is a significant time commitment. I suspect it will take several years for the gallery to become reasonably well known.”

Krause agrees on that.

“I don’t know how this is going to turn out,” he says. “On the other hand, if you don’t follow your dreams somehow, you’re going to wind up bitter and kind of frustrated by the fact that you never really did what you always wanted to do. My brother-in-law died last February. And he had been ill for three years. And there were just a whole lot of things that kind of happened and came together that made me think that really, this is the time. I hope that I’ll see some light at the end of the tunnel one of these days, because if it doesn’t work, at some point I’ll be spending my retirement money on it.”

And yet, he adds: “I can’t imagine a better way to retire—because it isn’t retiring—than doing something you really have always wanted to do. At some point I’m going to have to be very cold and calculating about the money I’m spending. But for right now I think it’s going okay.”